There is a cheeky chimp inside me who takes ignoble pleasure in noting the revealing relationship between artists and gongs. As a basic rule of thumb, the greater the artist the less chance there is of them accepting a knighthood, CBE, OBE, MBE or, finally, membership of the Royal Academy. History provides the evidence.

Neither Constable nor Turner were knighted. Nor were Hogarth and Gainsborough. On the opposite side of the ledger we have Sir Hubert von Herkomer, Sir Luke Fildes, Sir Martin Archer Shee, Sir William Llewellyn and any number of Who He’s.

When it comes to Royal Academy membership the same sorts of ratios apply. Bridget Riley, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach never joined. And though David Hockney is a busy Royal Academician thesedays, for the first 50 years of his career he was a fierce and vocal critic of the institution. As for Francis Bacon, he wouldn’t have been seen dead in the place. Until he was actually dead.

However, a close relative of my inner chimp appears now to have taken over the bookings at the RA and fixed it for Bacon to be the subject of a show that is so gripping and potent that it left me with residual shakes. Good exhibitions stir you. Brilliant ones attack you.

The idea that guides Francis Bacon: Man and Beast is that humanity, as understood by Bacon, was another branch of the animal kingdom. We have a beast within us and it needs facing up to.

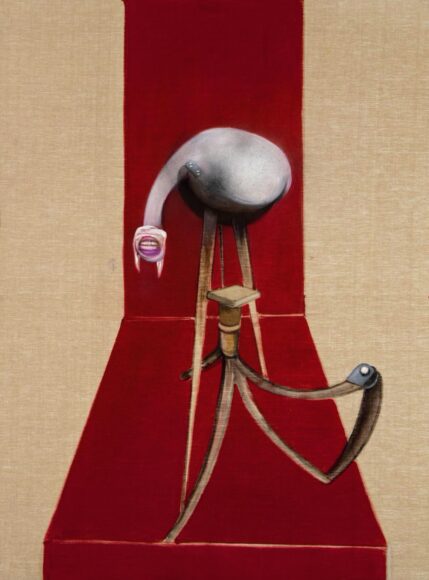

The point is made straight away by the first picture we see, Head 1, painted in 1948, isolated on one wall, bristling with pessimism and anger. Against a black background, on which a few quick lines have implied the presence of a cage, we see the shoulders and head of a shadowy figure. The top of the head is missing. All that remains of its identifiable features is a single ear and a snarling mouth. The ear is human. But the fanged and screaming mouth is not.

This dark notion that humanity is another branch of the animal kingdom is hardly groundbreaking. We can almost dismiss it as a cliché. But two factors at work in Bacon’s twisty response to the belief turn it into an extraordinary piece of artistic motivation.

The first is the mood of the times. In 1948 the war had only just ended and the sins of the Nazis were still a part of the present. Events at Auschwitz were being detailed. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were recent outrages. If ever there was a time when a sophisticated understanding of humanity’s nature was unnecessary, it was in the years in which the opening stretches of this event are set.

What also becomes clear as the show unfolds — factor two — is that the impact of the man-beast analogy on Bacon’s painting was astonishingly fertile. It kept feeding him new food. Even his touch, the scratchy and instinctual way he applied his paint, looks as if it was learnt from something in a zoo rather than someone at an art college.

The captions tell us that he grew up on a stud farm in Ireland and that the education he received about life from the farm beasties stayed with him. Horses, though, seem never to feature. Instead, the most insistent of his comparisons blurs the divide between humans and monkeys.

The fanged mouth of the screaming ape keeps recurring. It’s a comparison that was still shaping his views when he began his great sequence of screaming popes. On the outside we have the leader of the Catholic church. On the inside we have a screeching baboon.

The 1950s were his wonder decade. The central gallery here contains as riveting and inventive a grouping of paintings as I have seen in years. As you slo-mo round them, glued to the walls, the confessional fierceness of this furious identification with the animal kingdom becomes increasingly evident: he’s talking about himself, not about you.

Two naked men, half glimpsed in the long grass, display their buttocks animalistically as they wrestle. His lover, Peter Lacy, usually the punisher in their brutal relationship, curls up on the edge of a sofa like a beaten cur. Dog lovers — this is not the show for you!

Painted when homosexuality was illegal, the sweaty insights into his sexual preferences are furtive and tense. The relentless identification with animals seems always to involve thinking the worst of yourself, never the best. Pictorially, however, it leads to brilliant solutions. Especially in the paintings in which Bacon compares his wild animal self with the tameness that he sees in the rest of us.

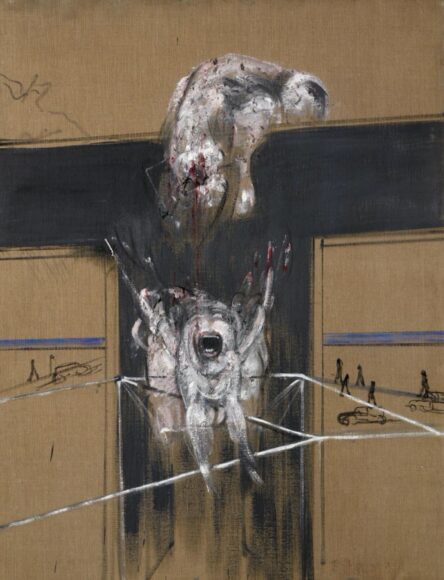

The masterpiece in this dark genre is a 1950 painting called Fragment of a Crucifixion. The screaming blob at the centre, representing the tortured Christ, started out as a photograph of a hunting barn owl. That’s how crazily inventive he can be. A T-shaped shadow on the wall forms the cross. And behind it, glimpsed through a window, are some tiny figures strolling by and driving their cars. That’s us: the unsuspecting passers-by. We haven’t got a clue what’s really happening in the house across the road.

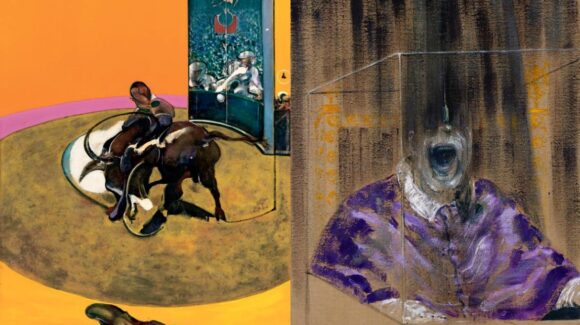

As the show progresses and Bacon settles on his signature style — brightly lit arena; warped figure at the centre — the level of invention decreases and the saturation levels go up. A show that had felt black and white at its outset becomes brightly coloured, and the grit and decrepitude of the opening salvos is hidden behind foregrounds as big as billboards.

A trio of bullfighting scenes that have never been seen together before offer unmissable proof of the glamorous international lifestyle that Bacon was now leading. The furtive humping in the grass has grown into a Hemingway-sized contest in the sun.

The bulls, when they appear, take up a lot of space. But it’s the snivelling curs that I can’t forget.

Francis Bacon: Man and Beast, Royal Academy, London W1, until Apr 17