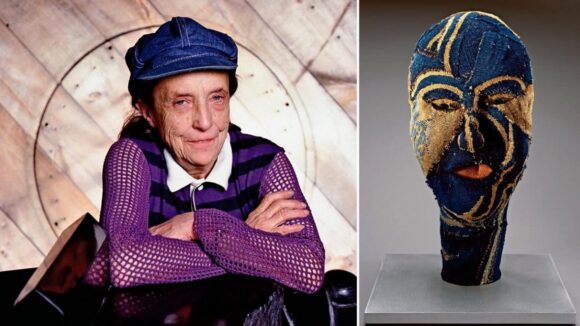

To cut to the chase on the subject of Louise Bourgeois, she was one of the most important artists who has ever lived. It’s that simple. Note I did not write talented, inventive, brilliant, although she was all of those things too. Plenty of artists have been talented and brilliant. But it did not make them important in the way Bourgeois was important. Art was one kind of world before she emerged — and another afterwards.

Her backstory is crucial, so here are the bare bones. She was born in Paris in 1911. Her parents were textile restorers specialising in tapestries. In her twenties she decided to become an artist and began moving in surrealist circles before meeting the notable American art historian Robert Goldwater and moving with him to New York.

They had three sons and although she exhibited now and then her middle years were devoted mostly to bringing up a family. Goldwater died in 1973. She was in her sixties. Slowly, inexorably, she began coming into her own. By the mid-1980s her name was on everyone’s lips. When she died, in 2010, at the magnificent age of 98, she left behind an art world filled with newly opened doors.

It’s an exemplary story because it coincided so exactly with a moment in art history when feminist voices began asking why so many female artists had been forgotten. As Bourgeois rose to prominence she prompted the question: how many more are out there? It was also a story of a mature European sensibility having a profound impact on American art. If ever there was an artist without a pixel of pop art banality in her make-up it was Bourgeois.

You see all this evidenced vividly at the Hayward Gallery, where a tremendous show has arrived to remind us of her impact and immerse us in her edgy, nervy, exciting way of making things. Called Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child, it focuses on her fabric works: the pieces she made with cloths and textiles in which her background as the daughter of tapestry restorers is clearly proven. By working with materials drawn from the domestic arena — “women’s materials” — Bourgeois fertilised art with a vigorous new feed.

The first piece we see proves the case. A set of battered old doors, banged together into a circular hut, encourage you to peep inside at a mysterious scene: items of feminine nightwear hang from hangers made of animal bones; a metal spider lurks on the ground; a spooky steel model of a house sits on a ledge.

Called Cell VII, this troubling take on the notion of a doll’s house feels immediately Hitchcockian. The eerie arrangement of domestic items — a fluttering nightie, a drooping petticoat — prompts fretful imaginings. And although no one mentions sex or family terror or a little girl’s fears, all these topics seem to be being addressed.

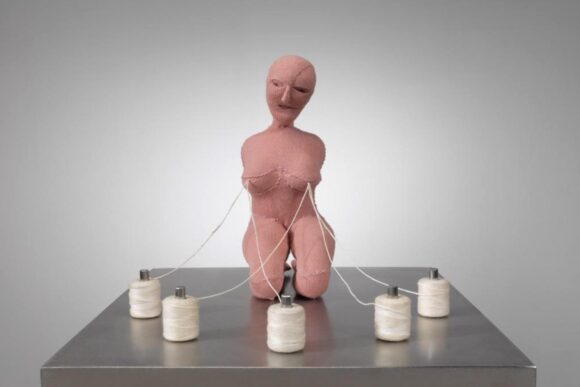

The downstairs spaces at the Hayward are busy with creepy sights in which empty bits of clothing stand in unsettlingly for missing human presences. It’s a process that feels closer to voodoo than to traditional sculpture. The bits of old clothing and the fragments of domestic interior bring an unspoken eloquence to her art.

A row of heads stitched loosely together from fragments of tapestry and blanket seem intent on describing anxious states of mind. They’re just bundles of quickly stitched cloth, but they manage to capture such precise expressions: screaming, dreaming, staring blankly.

Cell XXV, subtitled The View of the World of the Jealous Wife, is one of many works that seem to be admitting things from Bourgeois’ own past to illuminate bigger truths about the male-female divide. This time the bodiless clothes hanging inside a cage are Bourgeois’ own — a pretty blue evening gown, a housewife’s dress in white cotton. They have been hung so that one appears to be staring suspiciously at the other.

The cut of the evening gown emphasises the breasts, and two large marble spheres sitting pointedly in the cage combine with a hanging dress to form an erect penis. Nothing specific has been said on the subject of jealousy. But it is tangibly the subject here. Something else that’s going on is that Bourgeois is remembering the moods and methods of the surrealists she knew in Paris before she left for New York. On top of everything else she was, after all, a living link with the surrealist heyday of the 1930s.

It’s especially evident in a series of black sculptures of couples having sex in a vitrine. They don’t have heads. They don’t need them! Some don’t have legs. They don’t need those either! The grim evocations of joyless sex acted out by stuffed sacks of cloth hark back to the sex dolls of Hans Bellmer and the fetishistic mannequins of Man Ray. The caption tells us they also relate to Bourgeois’ own childhood mistake of walking in on her parents having sex: to the traumatised child, sex and violence are indistinguishable.

Using cloths and domestic fragments to deliver these sorts of edgy psychological messages is a stroke of genius. The most haunting of all the works in a haunting show is a tiny cloth figure of a striding man who has lost his leg and walks with a crutch. His only other distinguishing feature, quickly stitched again, is an erect penis. Leg or not, men will be men.

The sense of a world being observed and judged by darkly experienced feminine eyes continues for the whole event. It is one of the big new understandings she brought to art. In the downstairs galleries, where the work is displayed in a cluttered fashion, the claustrophobia seems to enlarge the impact of the art. Upstairs, where everything grows more spacious and seems less fiercely personal, there’s a drop in intensity. Frankly it’s a relief.

Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child, at the Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until May 15