Tate Modern has mounted a surrealism show. No surprise there. Surrealism is uber-trendy in the art world. Even the Venice Biennale, the most prestigious of all contemporary art events, will be focusing on it this year. Tate Modern is merely doing what we have come to expect of our leading establishment gallery of modern art: the same as everyone else. What is a surprise is how badly, how bleakly, how unartistically it has done it.

Surrealism Beyond Borders is an airing of relentless night-school politics hitching a ride on record-breaking quantities of poor art. The attitudes being aired are what we expect these days from the contemporary art establishment. What turns this effort into a particularly grim fail is the evidence it provides of an aesthetic collapse at Tate Modern. Have we really plummeted this low in our ability to tell good art from bad? It seems so.

When surrealism started in Paris in the 1920s, its chief ambition was to follow the advice of Freud and liberate the unconscious mind. The instruction took creativity to some dark places. The roped and amputated sex dolls of Hans Bellmer, featured in a tiny corner of the Tate, were one result. The showy visual twistings of Salvador Dalí, represented here by his celebrated lobster-turned-telephone in which the lobster’s sex organs form the telephone’s mouthpiece, were another.

But the obsession with deviant sex is not what sank surrealism. The macho posturing was survivable. What sank it was the all-access pass the movement handed to everyone and anyone to imagine themselves a profound artist. As the easiest of all art movements to do — drag up something squelchy from your psyche: convince yourself that squelchy equals deep — surrealism became an international magnet for the untalented. The Tate show did not set out to prove this, but it does exactly that. The stated ambition is to highlight surrealism’s internationalism and broaden its timescale. We should stop thinking of it as a Parisian art movement of the 1920s and 1930s, goes the argument, and see it as a liberating artistic tendency with a global reach. Egypt, Japan, Iran, Mexico, Turkey, China and Nigeria are all roped in. Instead of Paris of the 1930s, the exhibition time-machines us around the world till it reaches the edges of today.

A few classic surrealists have made the cut — Dalí, Magritte, Ernst, Miró — but they sit uncomfortably in the new mix. Mainly because they are so obviously better than their fellow exhibitors. Picasso pops up in an archive section devoted to the Bureau de Recherches Surréalistes — with which he had nothing in common — presumably because his The Three Dancers belongs to the Tate and they had to squeeze it in somewhere.

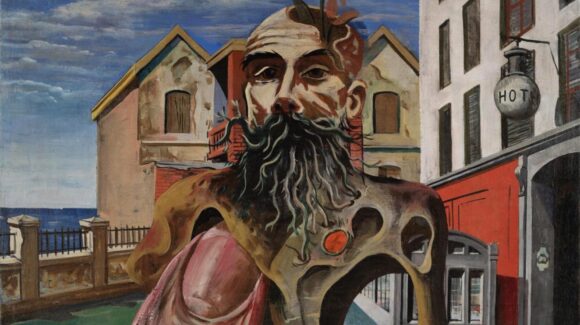

In the main, the show features artists of whom most of us will not have heard. This ought to be a good thing. But one of surrealism’s central problems is that in the hands of its lesser lights so much of it looks the same. Once you’ve seen one mutating blob you’ve seen them all.

To combat this sameness, the show tries to split itself into meaningful compartments — poetic objects, uncanny connections, the impact of dreams — but the art itself refuses to fit the curatorial pens. Seventy per cent of the exhibits look as if they were made by the same artist.

A point made relentlessly — by the curators, not by the art — is that surrealism was the go-to movement for revolutionary impulses and anti-colonial feelings. In Cuba, China, Egypt, Brazil, it prompted the formation of radical groups demanding change. But the artistic psyche being what it is, the artists picked out to exemplify this curatorial message do nothing of the kind.

Ramses Younan, who is involved in the Egypt section, supposedly as a mark of his stand against the Cairo authorities, gives us yet another suite of metamorphosing blobby nudes. Ted Joans, an American from the 1960s who was also a jazz poet, starts off one of those pass-it-along-to-the-next-chap artworks that they call an “exquisite corpse” with a big vagina. Of course he does. As an impulse that is essentially ego-driven — these aren’t any old blobs, these are my blobs — surrealism will always shout “Me” louder than it shouts “Us”.

The community aspect has to be wished upon the artworks by hectoring wall texts and case after case of deadening archive. The wildness, the excitement, the danger, the magic of surrealism have been expelled from the show.

Where this effortful illustration does give way to something more spiky and interesting is in the work of the female artists included in the trawl. The search for the “forgotten women of surrealism” has been one of the more determined efforts of recent art history. This event duly features Dorothea Tanning, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Joyce Mansour, along with a cornucopia of lesser-known surrealist Amazons.

Unfortunately, their work is scattered widely about the mess and a chance to say something concrete about their contribution is missed. What remains discernable is how the material dredged up from the feminine psyche differs radically from its male equivalent. Instead of breasts and vaginas, women surrealists give us psychic storms and esoteric beliefs, creepy stories and unsettling superstitions.

All through this event there’s a sense of a war being waged against reason. Sometimes it’s like wandering into a meeting of antivaxers. But where the masculine urge to fight oppression with nudes and vaginas feels absurd, the female retreat into alchemy, magic, theosophy and the esoteric results in art that is genuinely weird and disquieting.

At last — some proper surrealism.

Surrealism Beyond Borders is at Tate Modern, London SE1, until Aug 29