Aquestion. What is the second most spoken language in England? Answer: Polish. In the UK it’s the third most spoken after English and Welsh.

Another question. When Empire Windrush docked in Tilbury in 1948 carrying all those hopeful arrivals from the Caribbean, there were 66 displaced Europeans on board as well. What nationality were they? Answer: Polish. The war had flung them far and wide, and the Windrush was bringing them home.

And another question. The 16th-century Protestant reformer John à Lasco was one of the creators of the Church of England. Where did he come from? Answer: Poland. His real name was Jan Laski.

I ask all this not to prepare you for an appearance on Mastermind(you have two minutes on the Forgotten Inhabitants of Britain) but because a sense of puzzlement has been growing in me about the lack of attention paid to Britain’s most silent minority.

There are something like a million Poles living and working on this sceptred isle (although some have left after Brexit). They’re everywhere. They build, they drive, they plumb, they nanny. Yet for some mysterious reason we never hear from them or about them. While everyone else in diversity Britain seems to be importuning us furiously with this or that identity issue, the Poles remain silent.

This Trappist reserve is baffling. The Polish national story makes Game of Thrones look like an episode of Countryfile. Stuck between the Russians and the Germans, with no natural borders on either side, this is a nation that has spent most of its history fighting for an outline. Nowhere in Europe has a past as action-packed and tragic as Poland.

Yet can anyone out there remember a single meaningful broadcast on the subject? Not the Hairy Bikers on how to cook pierogi, but something serious about the wars, the revolutions, the invasions, the years of communism. Someone please tell us, why were there 66 Poles on the Windrush?

One day we may, perhaps, find out. In the meantime, a tiny trickle of cultural events has been trying to share some nuggets of information. This year the Matejko exhibition at the National Gallery in London was centred on a portrait of the great Polish astronomer Copernicus, who proposed that the Earth moves round the sun and not the other way round.

On the radio Melvyn Bragg recently investigated the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and revealed that at its apex, in the 1700s, it was the largest and most diverse nation in Europe.

Now the William Morris Gallery in Walthamstow, east London, has unveiled a rousing survey devoted to Young Poland, the Polish arts and crafts movement, which many consider to be the nation’s most resonant cultural achievement. The Poles themselves may be silent, but their art has begun to speak.

Young Poland flourished between 1890 and 1917, so in the years when Poland did not exist. Its beautiful neighbours — the Russians, the Germans, the Austrians — had divvied up the land and Poland had disappeared from the map.

But that’s just geography. Where it counts, in the heart, in the unbreakable substance of a national spirit, Poland was still there. Young Poland was the proof.

The artists involved in the movement were trying to create a national art style that was simultaneously modern and rooted in the past. The William Morris Gallery is the perfect location for the telling of their story because something similar happened in England with the emergence of the Arts and Crafts movement.

The lovingly handmade art objects produced by Morris & Co were an attempt to bring beauty back to an industrial world that had mechanised too quickly, too crudely; a world that had forgotten beauty’s importance. What looked superficially like a turning back of the clock to ye olde handmade Englande was actually an attempt to reconnect the nation with its endemic creative spirit.

Young Poland, a movement that produced chairs, houses, clothes, ceramics, tapestries, as well as paintings — all of which the William Morris has sought heroically to squeeze into its cosy premises — had similar ambitions, but with one significant difference. In the lands that were formerly Poland, the Industrial Revolution had not yet arrived with any force. Young Poland’s fight was not with dark satanic mills but with belligerent neighbours who had stolen the national past. The belligerent neighbours had sought to magic it away. Young Poland sought to magic it back.

Based in Krakow, the former Polish capital, which had managed to survive the national disappearance with its medieval character intact, Young Poland was an artistic war on many fronts.

Stanislaw Witkiewicz, the leader and William Morris figure in the set-up, was a playwright and a painter, a furniture designer and an architect. Stanislaw Wyspianski, the movement’s greatest talent, didn’t only possess some of the most beautiful drawing fingers of the European fin de siècle, he also designed theatre sets, stained glass for churches, as well as the compulsory Young Poland wooden chairs that look excellently Slavonic but are fiendishly uncomfortable to sit in.

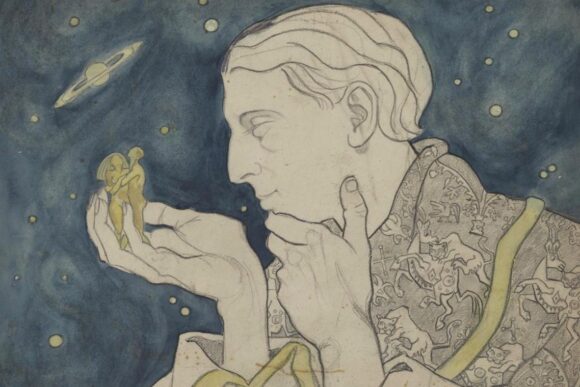

Not content with providing one of the toughest names in art, Maria Pawlikowska-Jasnorzewska was a poet as well as a loopy visionary who painted portraits of her husband sitting in the cosmos surrounded by stars.

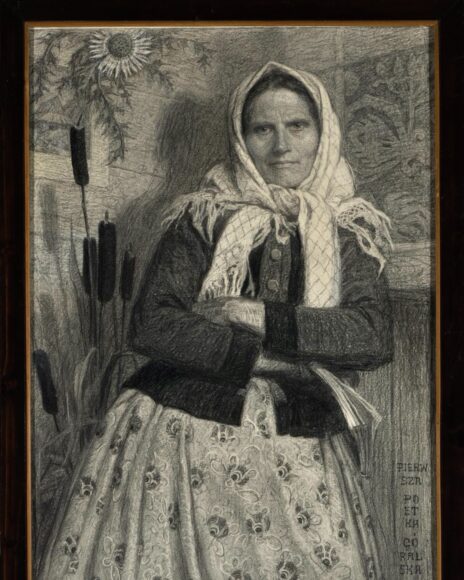

The exhibition telling their story has elbowed its way into the William Morris Gallery and manages even to take over the stairs, where some costumed Polish mountain folk have popped up waving mountain axes. These are the “gorale”, the inhabitants of the high Tatra mountains whose folk art became Young Poland’s primary influence and was chiefly responsible for the uncomfortable chairs.

High up in the Polish mountains, the gorale had managed to survive the turmoil in the lowlands with their customs and their craft untouched. So they became a touchstone for Young Poland’s artists, a living link with Poland’s pre-partition past.

Thus Karol Klosowski from Zakopane isn’t just another of Young Poland’s exquisite draughtsmen. He also made astonishingly intricate paper cut-outs, masterpieces of symbolic folk art, produced with nothing more than a pair of scissors. It’s another gulp moment in a show that has lots of them.

Young Poland, William Morris Gallery, London E17, until Jan 30

So you think you know about Poland…

1. In 1783 Poland became the first nation in the world to ban the corporal punishment of children.

2. In Shakespeare’s Hamlet the character of Polonius is named after the Latin for “Polish”.

3. Julius Fromm, the inventor of the rubber condom, was a Polish Jew from Konin.

4. The Bledow Desert in Poland is the only genuine sand desert in Europe.

5. The word “slavery” comes from “Slav”. For the whole of the first millennium Slavs were the go-to European slaves.

6. Marie Curie, née Maria Sklodowska, who discovered radium and polonium, was the first woman to win a Nobel prize, and the only one to win one twice.