It must be something in the water. Or perhaps the wind as it whistles up the Mersey and delivers the smell of the sea to the centre of Liverpool. However it gets transported, what’s certain is that there’s a sense of independence and a note of seriousness to Liverpudlian art shows that you just don’t find in other cities. Scouse shows never parrot what the rest of the art world is parroting.

Exhibit A in this outrageous claim is the Lucy McKenzie exhibition that has opened at Tate Liverpool. Exhibit B is the Deborah Roberts display that has turned up at the Bluecoat, Britain’s oldest arts centre. For two such potent shows by female artists to open in the same week in Liverpool is surely evidence of the stirring independence of Scouse aesthetics.

McKenzie, born in Glasgow in 1977, is both established and mysterious. You regularly see her work in significant shows, but never with that clear and obvious sense of being in the presence of an artist of rank. The top tens of female artists in British contemporary art tend to miss her out. She’s a leading figure, yet the notes she strikes are elusive and minor.

Her retrospective, ranged across the top floor of Tate Liverpool, is neither properly chronological nor properly thematic. Instead it veers in and out of both lanes as it attempts the task of keeping up with her twisty thinking.

She’s usually imagined as a painter, but from the first room it’s obvious that she is also a sculptor, a maker of installations, a poster artist, an actress, a dressmaker, and various other roles that are tougher to define. The Greek philosopher Heraclitus famously pointed out that no man ever steps in the same river twice, but this event would have Heraclitus breaststroking crazily from bank to bank as he sought to ascertain the true direction of McKenzie’s flow.

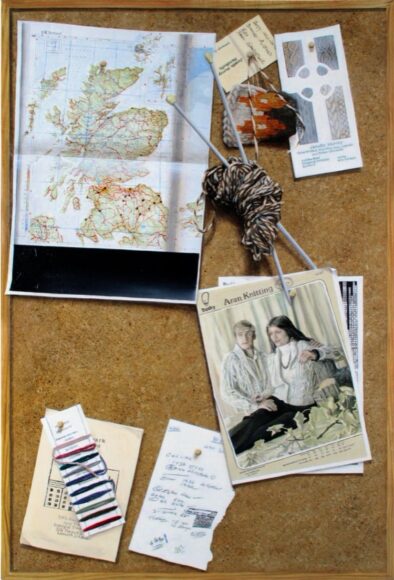

She is best known for her trompe l’oeil art. That’s where I first noticed her. Trompe l’oeil is a style of painting that sets out to fool the eye by being astonishingly realistic. McKenzie specialises in noticeboards on which are pinned intriguing assortments of things — cuttings, postcards, letters — which look real, like a photograph, but aren’t. Everything is painted.

The cuttings and postcards have been precisely selected to give a sense of their owner, so this is portraiture and symbolism working together inventively. As I said: twisty. What’s certainly impressive is the skill being displayed — there really is something magical about convincing trompe l’oeil — and also the independence of her ambition. No one in contemporary art is doing anything like this.

And it isn’t just her attention that darts hither and thither. So too does her skill set. In a cod detective film about Miss Marple she plays the lead role and goes briefly nude on us. Elsewhere she runs a fashion label, with the clothes on sale in the gallery. In posters of the Munich Olympics she plays Olga Korbut. One of the best rooms in this absorbing retrospective is devoted to the maps she makes that never show what you think they show.

Her most reliable interest, however, is architecture. In Brussels, where she now lives, she studied at the world’s only art school where they teach illusionistic decoration: the kinds of 18th-century skills that can make a painted wall look as if it is made of coloured marble. The first big exhibit here, a spooky recreation of the house built in Prague by the modernist architect Adolf Loos, looks as if it is made entirely of blocks of green-veined cipollino marble. But it’s painted canvas.

Loos was famous for demanding the stripping of ornament from modern architecture. His houses are strikingly spare and rectangular. But the real meaning of McKenzie’s “tribute” to him becomes evident only later in the show when she includes a book by him in one of her trompe l’oeil table tops alongside the writings of Eric Gill, Graham Ovenden and René Schérer, all of whom either supported or indulged in paedophilia. Loos was convicted of the same crime in 1928. Beneath the unornamented discipline of his sparse modernism, dark stuff was lurking.

This perhaps is McKenzie’s most consistent message. There are two sides to everything: what you see and what’s really there. She’s clever, adventurous, brave, original, and so is her show.

At the Bluecoat, Deborah Roberts dominates an exhibition by three black female artists. Sumuyya Khader, a Liverpool painter, gets a room to unveil her par-for-the course identity art. Rosa-Johan Uddoh, a Londoner whose identity art is refreshingly cheeky, gets the attic. But it is Roberts, from Austin in Texas, who’s the Gulliver at the event, towering over the Lilliputians in a big and airy display of power and poignancy.

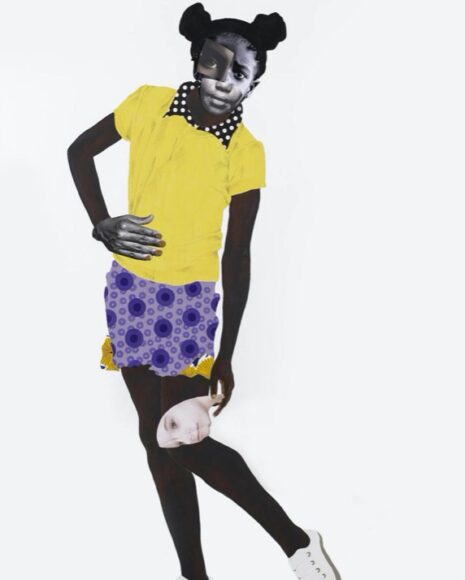

On the face of it her subject is black children. Street kids, ordinary and innocent, created out of a highly effective combination of collage and paintwork. Their faces, I read, she finds mainly on the internet, printing the photos to larger sizes, cutting them up and swapping them round, to achieve a universal kid’s look.

The clothes she invents herself, collaging together pieces of decorative cloth and patterning to create the kind of joyfully messy and unselfconscious combinations that kids wear. At least that’s the theory.

Yet somewhere along the line this light and innocent process begins to gain weight. By pinning her life-size portraits on to backgrounds of striking white, Roberts turns them into specimens. The faces she chooses, you begin to notice, are invariably sad and cast down. The poses too, which initially appear innocent and carefree, begin to complicate as you stare at them. The hands, often enlarged to adult size, begin to make sense as angsty adult gestures. Hints of eroticism drain away the innocence of the young girls’ poses.

What you begin to feel is the presence of Roberts, remembering her childhood, and transferring the doubts and problems she experienced as a black girl growing up in America on to her handmade stand-ins. Her chorus of mini-mes.

Lucy McKenzie, Tate Liverpool, until Mar 13. Deborah Roberts, Bluecoat, Liverpool, until Jan 23