Another autumn. Once again the nights close in and the rains descend. Once again the cry goes up: “Oh no. The Turner prize . . .”

The decline of Britain’s leading award for modern art — its transformation into a plaything of curators — has been one of the unhappiest sights of my spell as an art critic. In its heyday, the days of Rachel Whiteread and Tracey Emin, Gillian Wearing and Grayson Perry, the Turner was annually annoying — it could never stop that — but fulfilled a couple of sterling tasks.

First, it provided us with a summary of what was actually happening in British art. The display of shortlisted artists at the Tate offered something genuinely useful: an annual upsum.

Next, it gave us a winner we could squeal over and argue about, thereby shifting contemporary art from page 19 of the daily news to page 1. The choice was rarely, if ever, agreed on widely, but it gave the event a point and kept it honest.

Watching all this being thrown away has been heartbreaking. It has happened in the most painful way: strip by strip, in a series of dismal tinkerings.

First, they removed the “amateur” presence from the selection jury, thereby ensuring that curator spoke only to curator, and was left unhindered in their machinations.

Then, they widened the search for the best British art to events none of us had seen, in Australia, Berlin, Saigon, where jolly-loving art professionals had encountered them on their busy round of international biennale-hopping.

Sending the prize around Britain as if it were a national recruitment drive got it out of London, but increased the sense of machination. As did the scrapping of the age limit so that the Turner could become a long service medal instead of a career changer.

Finally, in the dismal year of 2019, when the four shortlisted artists declared themselves unilaterally to be the joint winners, the blighted annual brouhaha completed its transformation into an item of pure fake news. Where nothing is true any more. And nothing counts.

As evidence, I give you the Turner Prize 2021, an event so manipulated and phoney it makes 1980s pro wrestling look real. Instead of the best or most impactful art produced in Britain in the past year we have, by a miraculous coincidence, five fashionable “collectives” that have packed themselves into the Herbert Art Gallery in Coventry in the manner of the Keystone Kops filling a taxi.

The odds on it happening naturally, on five collectives simultaneously producing the best British art of 2020/21, would clean out Bet365 several times over. But this isn’t about the truth. This is about manipulating the public and promoting a world view that will make us better. In other contexts it’s called social engineering.

Thus the Array Collective, from Belfast, “create collaborative actions in response to social issues affecting themselves, their communities and allies in the North of Ireland”. As a collective, they are conspicuously supportive of the Protestant community in Ulster. Only kidding! Of course, they are not.

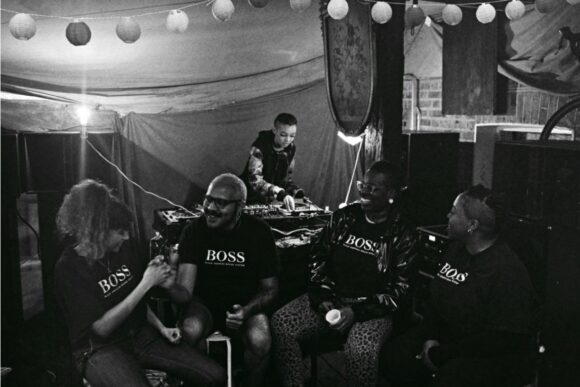

The Black Obsidian Sound System “was established with the intention of bringing together a community of queer, trans and non-binary black people . . . involved in art, sound and radical activism”. They believe sound systems are art. I do not.

Cooking Sections “examines the systems that organise the world through food. Using site-responsive installation, performance and film, they explore the overlapping boundaries between art, architecture, ecology and geopolitics.” Maybe. But the electronics needed to run their huge video installation will burn up a couple of small rainforests before the show finishes on January 12.

Gentle/Radical is “a collaborative cultural project . . . made up of activists, conflict resolution trainers, faith ministers, equalities practitioners, youth workers, performers, writers, teachers — and artists”. Phew. They squeezed some in at the end.

Finally, Project Art Works “collaborates with people with complex support needs . . . Their practice intersects art and care, and responds to neurodivergence, its gifts and impacts.” So they help people with autism or Alzheimer’s, and encourage them to make art.

These are all causes we should support. Those with autism or Alzheimer’s deserve our interest and aid. The food industry does need constant examination. And I like a good sound system as much as the next visitor to the Notting Hill Carnival.

Yet to be preached all this through relentless yapping and the skill-free employment of iPhone confessions and trade fair videos — which is basically what we get here — is an insult to the realities of art and the reason for its existence.

Humans did not invent art to improve other humans at events so transparently manipulated they make the smiling faces of the tractor drivers in a piece of Stalinist social realism look natural. Humans invented art to communicate deeper human truths in a visual language that did not rely on words. Yet in this electronic Tower of Babel, everybody’s talking, everybody’s accusing, everybody’s collectively shouting “me me me” as they drown each other out.

Is anything meaningful allowed to emerge? I counted three aspects of interest. The most obvious is that Britain appears to have turned into a nation of Ancient Mariners, every one of whom seems determined to grab you by the arm and tell you their story. Shush, o tortured souls, we all have a mum.

Simultaneously worrying is a scary unity of language, as if everyone who babbles at the 2021 Turner prize went to the same night class.

Third, and most unsettlingly, in the world of collectives our trust in science and reason appears to be regressing. Superstitious speaker after superstitious speaker voyages through their imagined spiritual past at an event that feels, in part, like a congress of antivaxers.

Thus Aleona from Gentle/Radical tells of the time she went to Haiti and was visited by a voodoo deity who made her smell nice, even though she hadn’t showered. While the comic priest in the Array Collective’s sermon in a pub remembers the faith that previously united the fairies of Belfast.

It’s actually the best thing here, and if we must have a winner at this festival of curatorial machination, let it be the Array.

Turner Prize 2021, Herbert Art Gallery, Coventry, until Jan 12