It was always going to happen. Art’s oldest method was always going to emerge from the tomb. Having spent many modern decades being deemed old-fashioned and irrelevant by the controlling middlemen of art, the curators, painting was always going to stage a big return. The question was: when?

A nifty new Hayward Gallery survey called Mixing It Up has decided the answer is: now. Showcasing the work of 31 artists, mostly at the start of their careers, but with a few oldies thrown in for ballast, the event argues that painting does things no other medium can do and that, far from being backward or irrelevant, it is the perfect medium with which to explore the fragmentary nature of the modern world.

It’s true, and definitely worth noticing. What is perverse here is that it is the Hayward Gallery, a venue run by Ralph “Mr Semiotics” Rugoff, a curator who has previously appeared allergic to straightforwardness in his tastes, that is making the big claim. Expect other venues to follow.

What’s been going on? Well, for several years now it had become increasingly evident that the art favoured by the curators — let’s call it conceptual art for ease of meaning; all that stuff that uses up tons of space to say nothing much — was no longer a good look. Wasteful, unecological, indirect, conceptual art was serving amuse-bouches to a world that wanted chicken soup for the soul.

So various art world groupings began making a conspicuous return to painting. Chief among them were black artists, whose need to say something powerful about their past was too urgent to have time for the dicking about involved in conceptual art. In the Hayward show about 30 per cent of the exhibitors are black. And, as this column has often had cause to notice, when the world gets real, art gets real.

Lubaina Himid, the Turner prizewinning art agitator, opens proceedings with a huge view of the infamous 19th-century slave ship Le Rodeur, on which the past and the present, time-coded by the costumes worn on deck, some old, some new, hug each other across the ages. It’s impossible to criticise Himid for her politics. She says the right things at the right time. I just wish she were a more fluent painter. Her touch is so wooden you could carve a figurehead out of it.

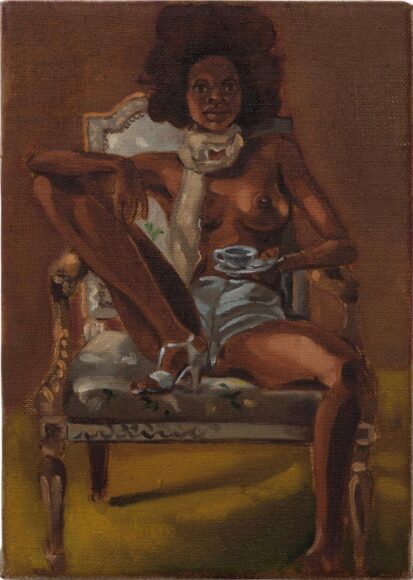

Not so Somaya Critchlow, a brazen painter of erotically charged black women whose brush whips around the canvas at Rubens’ speed. In Critchlow’s art the black nudes are displaying and staring. According to the caption, she’s examining “the power and the pleasure to be had in imagining yourself, in being looked at, and in looking back”. Not a line I would have dared to write, but one that rings true.

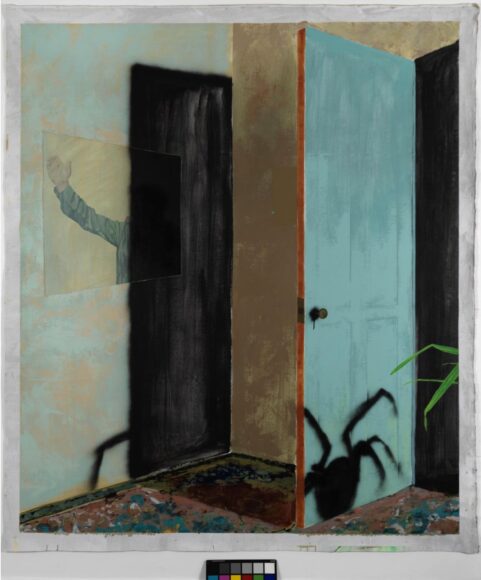

Back at the front line of serious art politics, Mohammed Sami, who was born in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, is among the best exhibitors. His slippery, fragmentary, faded paintings are pure Rugoff in their elusiveness. But as you spend time with them, they deliver big meanings through the excellent back door of poetry. Thus a hazy black chair propped against an angelic white door in a delicate pink room takes a while to be recognised as a barrier, put there to stop intruders from entering. But once you see it, the painting’s symbolic presence grows and grows.

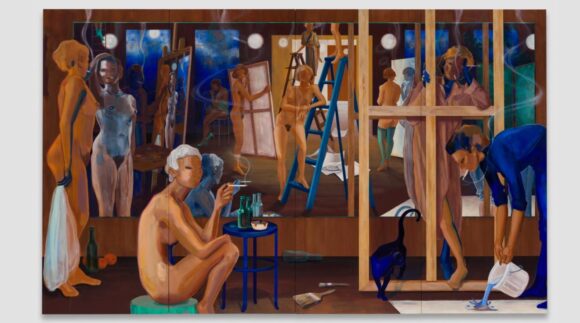

Sami is in the minority. Of the 31 artists included here, 18 are women with something fiery to get off their chests. For many it is the male domination of art that is the target. The increasingly impressive Lisa Brice, who seems to grow in stature from week to week, marches on to the macho territory of the artist’s “atelier” with a complex and amusing studio scene in which women have taken over all the art roles, and are now creators and models. To give them an immediately independent presence, she has them all smoking like blokes on a building site. Fabulous.

Why have women artists taken so happily to painting? In most cases directness doesn’t seem to be the aim. Rather, it’s the storytelling potential of the medium, its ability to flit nimbly from era to era, event to event, that is the attraction. A large chunk of the show’s feminine produce falls into the category of magic realism, which is to say the creation of fictional scenes in which anything is possible.

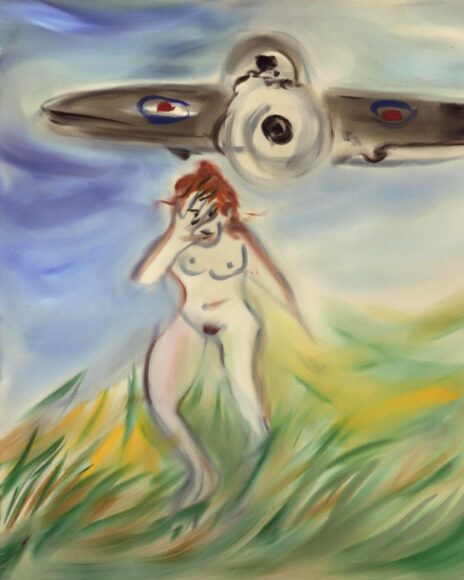

Sophie von Hellermann, another of the best discoveries, whose work has the wristy fluency that only true painters are born with, paints a naked woman running through the grass while a Second World War Spitfire buzzes over her head. Amazingly, the caption reveals the wacky scene to be a work of fact rather than fiction. It happened to von Hellermann’s German grandmother. She really was buzzed by a Spitfire and forced to run naked through the fields!

Painting is good for memories. It’s good for personal rumination. And running across the whole show is a sense that making art this way is especially pleasing. There’s also recurring evidence that Covid played a part, by forcing artists into a solo mood where they were alone with their thoughts.

The big disappointment, as a category, is abstraction, which gets plenty of space upstairs but achieves no convincing moments. Figurative art allows artists to hide a weak touch behind a big meaning. Abstraction does not. Oscar Murillo, who produces huge black monster scrawls, has the kind of skill set that is needed to tarmac a motorway. What he shouldn’t go near is a paintbrush.

Quick coda: there will be a lot of painting shows in the near future. Then they will stop, and people will say painting is dead. A few decades later painting will come back. It always does.

Art from the front line

Smoke and Mirrors

by Lisa Brice (2020)

Set in a busy artist’s studio, packed with naked women, Lisa Brice’s Smoke and Mirrors, pictured above, is a feminine land grab of some archetypal male territory. Note the blue paint being poured on the right, a sarcastic reference to Yves Klein’s notorious Anthropometries, made by dragging naked women through blue paint.

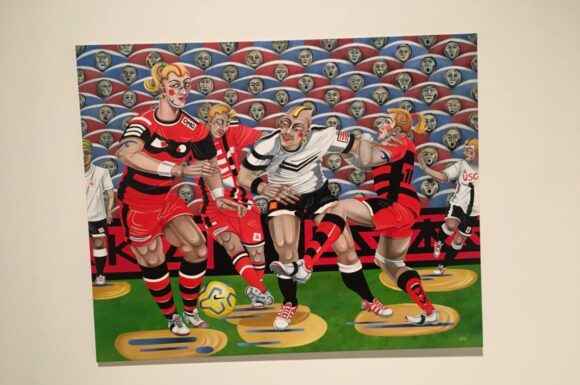

Rugged Defensive Play

by Caroline Coon (2020)

Football is rarely tackled in art, but Caroline Coon, a co-founder of the drugs charity Release and a former writer on Melody Maker magazine, has a passion for it. In Rugged Defensive Play she turns a moment in a game into a piece of Noh theatre.

Infection II

by Mohammed Sami (2021)

Sami was born in Iraq. Lurking in every space he paints is a sense of threat. Here, the shadow of a house plant turns into a giant spider on the door, while Saddam Hussein’s raised arm is instantly recognisable on the wall.

Perfidious Albion

by Sophie von Hellermann (2021)

A naked woman runs through the grass while a British fighter plane swoops down on her. The frightened woman is based on von Hellermann’s German grandmother, and the event described actually happened.

Figure Holding a Little Teacup

by Somaya Critchlow (2019)

The black nudes painted by Critchlow are an attempt to deal with a traditional art subject from a new feminine perspective. We stare at them, they stare at us. And the question is asked: “Who’s looking at whom?”

Mixing It Up: Painting Today, Hayward Gallery, London SE1, until Dec 12