Tate Modern is on a mission. The gallery is hoping to enlarge the reputations of female artists who have been forgotten in our masculine art histories or were never noticed in the first place. Lord knows there are a lot of them.

It’s a noble mission. And the Sophie Taeuber-Arp show that has arrived at Tate Modern can be seen as part of this effort to correct the impression that female artists played a negligible role in the unfolding of modern art. On the contrary: they were there, they were plentiful, they were important. Why, therefore, have so many slipped down the back of the sofa?

The easy answer is: because the masculine art world put them there. The alpha males of modernism — the Picassos, the Duchamps — saw women as goddesses or doormats, and never allowed them the space to develop as fellow artists.

In the film about her life that opens the Tate’s reassessment, Taeuber-Arp can be heard complaining about the cooking she has to do when artist friends come to visit. Her husband, the celebrated dadaist Hans/Jean Arp, left the domestic chores to her.

If you have ever found yourself in the company of a school of male artists you will be familiar already with the sad phenomenon of “the artist’s wife”. These wretched creatures — the Cinderellas of creativity — cook, clean, have the kids, look after the house, deal with the homework and the gardening, while the Picasso they wedded strides from private view to private view searching for the spotlight. The surprise is not that so many “artist’s wives” had reduced careers but that so many had any career at all.

The female artists who preceded Taeuber-Arp in the Tate’s revisionist programme — Sonia Delaunay, Natalia Goncharova, Dorothea Tanning — all had partners who hogged the limelight. Tanning ended up with Max Ernst, the frantic German bedpost-notcher who jumped about between the forgotten women of surrealism like a cock in a hen run.

Yet even in her case there was evidence that the relationship with Ernst could also be fruitful. They shared a determination to be creative and unconventional, never had children, and Tanning was largely free to have the outstanding career recorded for her by the Tate. Why, then, did it take so long to notice it? The Taeuber-Arp exhibition points us to some answers. Born in Davos in Switzerland in 1889, when the town was still a pleasant Alpine resort and not yet the setting for the World Economic Forum, she had a crazily varied student career that involved hopping between art schools in Switzerland and Germany, studying textiles, design, drawing, metalwork, fine art, sculpture and modern dance. Yup. Modern dance.

The aesthetics that ensued from this merry-go-round of creativity are, from the start, featherlight and whispery; paper thin and agile; delicate as a fresh fall of snow. Easier to miss, therefore, than an art that is hefty, weighty and solid.

The show opens with a set of small, precise abstractions that she called her Vertical-Horizontal Compositions — most of her work has that kind of name — in which the methodical application of countless coloured lines, built up in layers, forms a delicate pattern of light-filled squares and rectangles. It’s a process not unlike embroidery in its repetition and precision.

The exhibition paperwork makes the excellent point here that by coming to these arrangements through an interest in textiles, Taeuber-Arp followed a different trajectory from the one pursued by the more celebrated pioneers of abstraction — Malevich, Kandinsky, Mondrian. They got there by starting with figurative ideas, then simplifying them. With her, the beauty of textiles revealed the joys of abstraction without an intermediary step.

Then the First World War breaks out, and she meets the annoyingly double-pronged Hans/Jean Arp who introduces her to dada. And the lovely early abstracts turn quickly into something else.

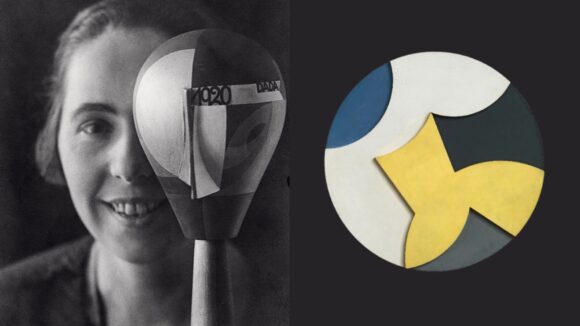

Dada used sarcasm and snippy humour to question the terrible realities of war. At least that’s what it usually did. But when Taeuber-Arp turns her talents to it, the darkness and angst swiftly scarper, replaced by a bouncy, multivalent creativity with no obvious sense of direction. She designs puppet shows, makes wooden sculptures based on milliner’s dummies, creates wacky costumes for modern dance and even dances the lead role in a poem ballet by Hugo Ball.

It’s about here that the show started to lose me. Not just because I am allergic to puppetry, but because a whiff of privilege and avoidance reached my nostrils. If you’ve seen Otto Dix’s horrifying art from the First World War trenches it feels wrong to skip over those moods as Taeuber-Arp, holed up in neutral Switzerland, managed to skip over them.

The jumpiness that characterises the show’s early stretches turns out to be career long. Most of the texts on the walls stress her versatility. The evidence is scattered lightly about four big rooms in the Blavatnik Building, where the looming spaces make the journey feel bitty.

In the 1930s, having moved to France, she designed a new studio home for herself and her husband. I don’t doubt it was an impressive achievement, but the single photo of the outside included here gives no tangible sense of Taeuber-Arp the architect.

In all this jumping about two areas of her activity manage to assert themselves. The first is her work with textiles, and especially the shockingly desirable geometric rugs she designed with their playful interplay of colour and form. Even better are the abstract paintings she made in France in the 1930s, under the influence of Le Corbusier and Ozenfant. Working with oils on canvas brings a sense of profundity and permanence to a vision that can feel light on both. But to get back to the original question: why has Taeuber-Arp not been given her due? The answer, surely, is: the changing context.

In art today multi-disciplinariness is all the rage. No one wants to be a Cezanne any more, spending their entire career working methodically towards a single goal. Contemporary artists want to jump about as they please from technique to technique, form to form, with an unrestricted sense of what constitutes their art. Taeuber-Arp’s example gives them licence to do that.

The materials they work with have also undergone a redrawing of values. These days, especially in the hands of female artists, the formerly “domestic” pursuits of textile work, sewing, embroidery, have been repurposed to powerful effect. Look at the brilliantly dark and edgy art made out of the contents of her linen cupboard by Louise Bourgeois.

In all this Taeuber-Arp (1889-1943) can be viewed as an important precursor. True, you need first to forget two world wars, a century of destruction, Hitler, Stalin etc. But hey, that’s just history.

Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Tate Modern, London SE1, to Oct 17