Occasionally in art a career pops up that is so different from the norm, it seems to have been thrown over the fence from another reality. Hieronymus Bosch had that kind of career. So did Caravaggio. Nothing prepares you for them. They suddenly appear.

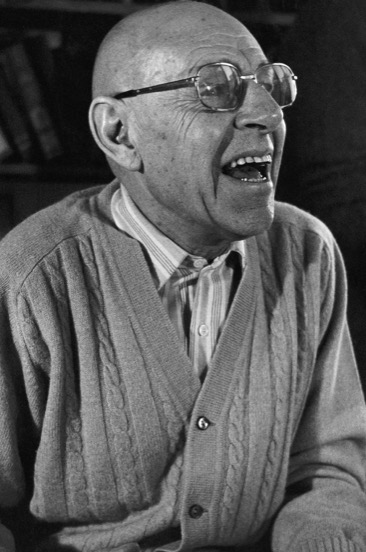

In the postwar years such a career was had by the thunderously eccentric Jean Dubuffet (1901-85), an artist who did most of his painting with a trowel and whose brusque and basic imagery seemed determined to maintain a connection with the art of the cave dwellers. Perhaps the last genuinely impactful French artist, Dubuffet spoke to the id of the postwar human in a language so blunt that anyone related at any distance to the chimpanzee could immediately catch its drift.

But as soon as the fear and loathing of the postwar years began to fade, so too did Dubuffet’s reputation. Indeed, it plummeted like a bag of horse ordure dropped from a barn roof. During my entire stint on the front line of art criticism not for a nanosecond has he been anything other than a profoundly unfashionable artist with a tangibly embarrassing presence. Until now.

Now he is suddenly the focus of a punchy retrospective at the Barbican Art Gallery, which needs to be recognised as an exceptional piece of exhibition making. Curated by Eleanor Nairne, the most exciting curator at work on the London circuit — she also did Basquiat at the Barbican and the marvellous Lee Krasner show — Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty is fiery and stimulating, beautifully installed, skilfully paced and even manages on occasions to be elegant. The only disappointment is the art. What’s that saying about polishing turds?

Born into a family of wine merchants in Le Havre, Dubuffet, whom I have previously suspected of being something of a chancer, certainly had a chancer’s life. Until the age of 40 he stuck mainly to selling wine, with a couple of detours into being an artist. During the Second World War he smuggled wine between occupied and unoccupied France, and made a stack of francs flogging pinot noir to the Wehrmacht. Accused later of collaboration, he was antisemitic (there’s a note on the show’s wall apologising for it) and however neatly he is presented here there seems always to be a stink of something horrid emanating from him.

The first work we see was produced at the tail end of the war — 1944 to 1946 — when he gave up the wine business and decided to style himself an artist. Largely untrained, 43 years old, he produced a set of tatty word pictures painted on old newspapers, inspired by the graffiti scrawled across the ruins of post-occupation Paris: “Emile is gone again”; “Georges arrives tomorrow morning.”

It’s miserable art, anarchic and deliberately pointless. Its ambition is clearly to side with the untrained and the inchoate. So it’s also an attack on traditional French notions of fine art. The same newspapers that Braque and Picasso had repurposed delicately in their cubist still lifes of the 1910s, Dubuffet, in the 1940s, was scrawling across like a drunk in an alley. (At the other end of the show the curator draws our attention to his subsequent influence on Basquiat, Keith Haring and the American graffiti artists. It’s a good point, and it made me suspect that she came to him through them. There had to be a reason!)

The graffiti art is immediately agenda-setting. He’s against the old ways. He’s against obvious notions of culture and taste. He’s against training. Against politeness. What he’s for, instead, is directness, passion, immediacy, uncouthness and destruction.

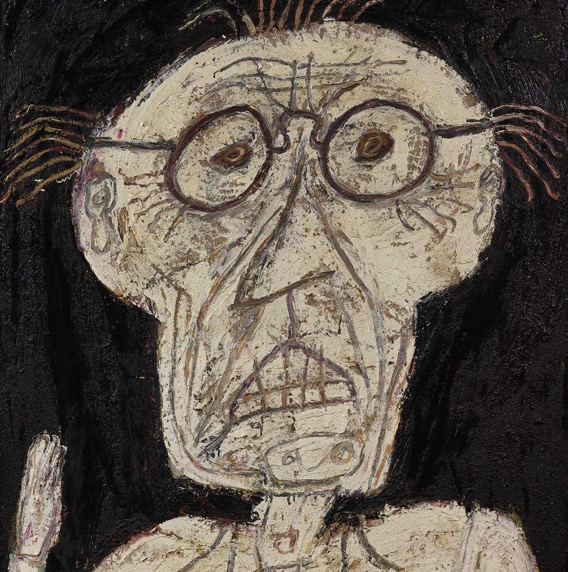

His most famous works, a set of primitive “portraits” produced as the 1940s clicked over into the 1950s, are an assault on every propriety going. Working with a sludge made out of oil, varnish, fag ends, studio dust, sand and, perhaps, his nail clippings, he begins by smearing a layer of this suspiciously brown stuff across the canvas and then gouges rough human shapes into it with the end of his brush. It’s an effect not unlike rock art, although Freud, had he had hung on a few years longer instead of dying in 1939, would surely have drawn parallels with a baby’s urge to play with its own poo-poo.

This deliberate turning of the back on propriety is easy to mistake for a class war — us v them — except that Dubuffet was a prosperous bourgeois who had traded profitably with the Wermacht. A truer way to read him, I reckon, is to see him as one of those aggressive French naysayers who delight so fully in saying “non”. Some become waiters. Some put on the gilet jaune. Some become artists.

He worked in clusters. Each of them gets a Barbican niche to itself. His “Texturology” paintings feature what appear to be slabs of earth hacked out of the ground and appended to the wall. A series of jollier pictures, his “Garden” art, in which he strives for a mosaic effect with brighter colours, turn out to consist largely of butterflies, murdered in their thousands and glued to the canvas with sticky glee.

Unexpectedly one of the few areas of his output that survives this effortful clumsiness is his portrayal of women. Yes, we are once again in the hands of a caveman, reducing his subjects to their biological basics, but Dubuffet’s blobby belles are so fiercely and determinedly unsexy, they appear to be fighting a fight against idealisation. “Nothing seems to be more false, more stupid,” he complained, “than the way students in an art class are placed in front of a completely naked woman . . . and stare at her for hours.”

In his own art there is never any sense of him responding to something he has seen. It’s always a case of imposing his vision on whatever territory he has marched into. Having taught himself to paint (sort of), he went on to teach himself to sculpt (sort of), producing scruffy figurettes with a distant kinship to the human figure.

Unable to find accomplices among the ranks of his fellow postwar artists, this unstoppable egomaniac gave himself a kingdom by descending on the self-taught and the mentally ill; on one-off creatives and like-minded loners. These days we call such output outsider art. Dubuffet came up with his own label: art brut. He collected it in bulk and founded museums devoted to it.

The show deviates briefly from its retrospective ambitions to include examples. Joaquim Vicens Gironella, a worker in a cork factory in Toulouse, used a penknife and a burning cigarette butt to gouge angry visages into lumps of cork. Aloïse Corbaz was a Swiss schizophrenic who fantasised about being the lover of Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany and illustrated her dreams in wild diaries filled with coloured pencil drawings. Laure Pigeon was a spiritualist who painted in blue blobs what her spirit masters instructed her to paint.

One of the identifying features of art brut is that there is an awful lot of it about. As Joseph Beuys said, “Everyone is an artist,” and all that. Thankfully the show’s curator is thrifty with the examples and includes just enough to illustrate the tendency.

The same thriftiness also keeps a lid on Dubuffet. In real life he was an unstoppable gasbag who was missing an off switch, but here he has been topiaried into something approaching a discernible shape. Happily some of his best work comes at the end, when he grows too old to pick fights and paints pleasing abstracts.

All this is exceptionally well told in a beautifully installed show that makes clever use of the Barbican’s brutalist architecture to punctuate a journey that would otherwise be largely free of punctuation. Turning bad art into a superior exhibition is more than good curation. It’s alchemy.

Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty is at the Barbican, London EC2, until Aug 22