Three of art’s more fruitful trends have been combined at Charleston, the Sussex abode of Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, the busiest of the bed-swapping Bloomsberries.

The first is the deployment of country houses as venues for exhibitions that are adventurous and au courant. You go there expecting strawberries and scones, but find art with fresh ambitions and a contemporary twang. Plus the strawberries and scones.

The second trend is the disinterring of female artists from previous ages whose contributions have been overlooked. Right now, in art, your best chance of being remembered in an ambitious retrospective is previously to have been forgotten.

The third trend we will come to once we have dealt with the first two at the Nina Hamnett show at Charleston.

In its heyday, Charleston was more rural bonk-shop than country home. The poster-perfect Sussex hideaway, with pretty ponds and flower-packed enclosed gardens, was where Grant would smuggle in his male lovers while Vanessa betrayed her husband, Clive, and everybody slept with Roger Fry and Maynard Keynes, or Lytton Strachey, and Vanessa’s sister, Virginia Woolf, inched her way through her tortuous sexual adventure with Vita Sackville-West. Pretty much the entire cast of intellectual 1920s Britain showed off everything it had learnt from rabbits at Charleston.

Nina Hamnett was cut from similar cloth. Born into a military family in Wales in 1890, she escaped to Paris in 1914 and began collecting lovers, male and female, at a prodigious rate, starting with Modigliani and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. In Paris she learnt to paint in a mildly modern style — cubism lite — and on her return to London found herself dangling in the Bloomsbury orbit when she worked briefly at the Omega workshop and took Roger Fry as a stud.

Later in life she turned into a performing alcoholic, who died by falling from her Fitzrovia window and impaling herself on the railings. Suicide or drunken tragedy? No one knows. Before it came to that, though, she was a painter, and by focusing on the years 1913-20 the Charleston show gives us the best of her.

This is the first survey of Hamnett’s art. The organisers have trawled though auction records and the private collections of friends and assembled a selection of 50 works: 30 paintings and a roomful of drawings. Their effort deserves lots of applause: it’s an admirable piece of curation. What it is not is the dramatic unveiling of a lost talent. Most of the evidence here points to a modest vision that should not be pumped up into something grand by wishful thinking.

It starts well enough with a set of glum still lifes — cups, vases on a table, a book, a newspaper — that have a tick-tocky mood, as if a clock on the mantelpiece is counting down the loneliness. They are followed by a clutch of circus pictures — the exhibition’s low point. The taste for circus scenes that afflicted European art in the early years of the 20th century dragged down better artists than Hamnett. Her efforts are, nevertheless, especially feeble, with wonky acrobats, vertiginous viewpoints and clumsy simplifications that reveal an innate inelegance in her line. A couple of glum rooftops from the same era appear to be searching for cubistic patterns in the domestic sprawl of London. All they actually discover is that Edwardian London was nicotine coloured. So far so weak.

Thankfully the rest of the event is dominated by the thing she was best at: portraiture. Her address book was clearly a thing of wonder. Was there anyone in bohemian Paris or fashionable London she didn’t know? The sculptor Ossip Zadkine, painted in 1914 yet already sporting a Monkees haircut, has his preternatural neatness compared with the sprawling primitivism of one of his sculptures. Walter Sickert looks out quizzically from beneath a bowler hat. Percy Fender, the famous cricketer who once hit a first-class century in 35 minutes, pops up among the artists and society ladies like a celebrity guest at a charity auction.

Most of this posh portraiture employs as its house style the aforementioned cubism lite, learnt in Paris. The shapes are angular, the poses simple, and there’s a sense that the figures have been carved out of wood and would look at home on the front of a ship. Cezanne, Modigliani, Picasso — the teachers are obvious.

Only rarely does the borrowed vision splutter into a life of its own. The dancer Constance Stewart-Richardson, famed for her revealing dresses, is the subject of a surprisingly sombre appraisal from 1917, which shows her wrapped in black, staring sadly into the distance and appearing twice her age: she was 34 but looks 60. Ouch.

Most of Hamnett’s portraits lack this psychological heft. The suite of her drawings, mostly nude studies, is just as inconsistent. Sometimes she’s spot-on — there’s a hilarious nude of Roger Fry crouched on the floor like a predatory tiger, with his bits dangling — but more often the encapsulation feels insecure. The sense persists of a modest talent that hasn’t fully found itself, and never would.

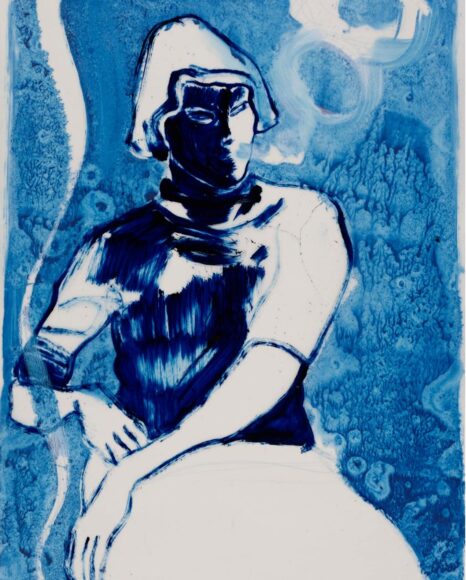

You’ll be wondering about the third trend. It’s the pairing of old artists with new ones. Double bills bring double the audience so Nina Hamnett has been coupled with Lisa Brice, a contemporary South African who, we keep being told, “contests the often misogynistic nature of art history”.

Rather mysteriously she does this by focusing almost exclusively on female nudes presented here in a lively ring of undressed poses, some of which have been borrowed from Courbet, Degas and Picasso. In Brice’s versions the nudes are invariably seen to be smoking, or drinking straight from the bottle, as if this barroom behaviour revealed something more authentically feminine about them. Surely a less knotty response here would have been not to paint female nudes at all? Oops, I’m mansplaining. Apologies.

In truth the imagery is spiky and interesting, and Brice’s line usually passes the nude test — one of the hardest there is — with good marks. What I’m unsure about is her insistence on using only blue paint for her work. It feels like a gimmick. And, like Baselitz’s upside-down figures, will surely start to pall.

Nina Hamnett and Lisa Brice, at Charleston, East Sussex, until Aug 30