They came from outer space, at least that’s how it felt. One moment there were no NFTs in the universe. The next moment they were popping up everywhere and multiplying crazily. It was like an episode of Doctor Who or, less fortunately, like the arrival of a virus. Art was imitating life.

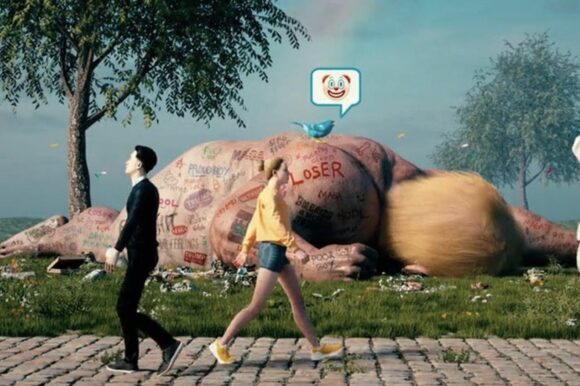

I first became aware of NFTs, or Nifties as the friendlier writers had renamed them, in the art press. It was late February this year. At an internet auction in America, a graphic artist who called himself Beeple had reportedly sold an NFT of a naked Donald Trump, covered in graffiti, for $6.6 million (£4.7 million). Slumped by a sidewalk, looking dead, the naked Donald had the word LOSER scrawled on his back. “Wow” we gaped, collectively.

Beeple’s real name is Mike Winkelmann. It turned out that giggly digital surrealism was his forté — characters from Toy Story chain-sawing caterpillars; President Lincoln spanking a baby Trump; Trump and Hillary Clinton sharing a spacesuit. Dumb and jokey, it was art for airheads, easy to make if you knew how to instruct a computer. So why in Buzz Lightyear’s name did it cost so much?

Art prices had been rocketing since the first lockdown. A bored generation of nouveau riche collectors, with holes where knowledge and taste should be, had discovered a fresh video game: bidding for art. Staring at their screens all day and all night, drifting ever freer of reality, they had transformed overspending into the new normal. Still, $6.6 million was a standout quantity of wonga.

NFT stands for non-fungible token. Back then — just before the third lockdown — we innocents in the British art world didn’t even know what fungible meant, let alone NFT. So a mad scramble through online dictionaries ensued, and after a few minutes’ furious tapping we were up to speed on the crypto fad.

“Fungible” is a legal adjective used in deals and transactions to describe something that can be exchanged for something else of the same value. “Non-fungible” is the opposite. Non-fungibles cannot be exchanged or swapped. And if this inability to be exchanged is formalised with a token recording your possession, you have something that can belong only to you: a non-fungible token.

So it’s all about ownership. Outside the digital world, the palaver would be meaningless. If we buy a painting in a sale, we take it home, hang it on a wall, keep the receipt and it’s ours. But inside the digital world, different circumstances prevail. If you, like Beeple, create snippy digital cartoons — he does a new one every day, and posts them on a website called beeple-crap.com — anyone can access those images and download them. And being digital, the downloads have the same value as the original artwork. Anyone can save them to their computer, open them, stare at them, like them. What they cannot do is own them. That’s where Nifties come in.

Using a digital security system called blockchain, developed for the trade in cryptocurrencies, Nifties are a way of recording your possession with an unbreakable and unhackable digital padlock. If you’ve bought the NFT for a Beeple artwork for a zillion bitcoins or a gadzillion ethereum, the blockchain guarantees that you own it. It doesn’t matter how many other bored screen-gazers around the globe continue to look at it — it’s yours, not theirs. You have the digital token to prove it.

NFTs were first put to collecting use by basketball fans. This was all the way back in 2019 when the National Basketball Association (NBA) in America issued a set of video clips, called Top Shot, in which stars of the game could be seen scoring spectacular points. Fans could buy and collect these Top Shots as NFTs. They were like digital versions of the old football cards that used to be found inside cigarette packets, where every member of England’s 1966 World Cup-winning team could be collected and stuck in a scrapbook. The playgrounds of Britain shuddered once to the sobs of tiny Bobby Charlton lovers desperate to swap a Nobby Stiles.

By issuing Top Shots as NFTs, the NBA made the digital clips extra desirable. Everyone could look at LeBron James scoring a super-dunk for the Lakers, but you alone owned the Top Shot. Within days it had sold as a Nifty for $200,000. A Zion Williamson block for the New Orleans Pelicans quickly matched it. It was like persuading football fans to bid for an action replay of Goal of the Month on Match of the Day. If it was your team, you were tempted. If you were a gambler you were tempted too because you could sell your NFT on the Top Shot website’s marketplace. The combination of sports ardour and crypto hyperbole quickly led to a collecting frenzy.

As soon as it saw the noughts, the art world wanted in. Beeple, who had been issuing his carcinogenic cartoons for 13 years without too many people noticing, was persuaded to jump into bed with a new internet franchise called Nifty Gateway. Taking the success of the NBA basketball cards as its model, Nifty Gateway began mounting regular auctions of digital art for a new audience of techno-savvy rich kids, weighed down by bitcoin and ethereum.

Few of these cyber-millionaires could tell the back of a Rembrandt from the front. What they wanted, instead, was poppy internet imagery that reminded them of their skateboarding days and that time they earned a record number of hearts in The Legend of Zelda. A generation that had grown up glued to a screen had discovered a new enthusiasm that didn’t involve moving an inch: bidding online. And arriving on cue to assist them in their inactivity was a virus that glued the entire world to its seat.

All this happened at LeBron James speed. Nifty Gateway was launched in March 2020 by identical twins with techy backgrounds, the unfeasibly named Duncan and Griffin Cock Foster. Inspired by the success of Top Shot, the Cock Fosters decided to expand the reach of NFTs into digital art. “Nifty Gateway was founded with a very simple mission — to make Nifties accessible to everyone,” shouts their auction website. They forgot to add “… as long as you’re loaded”.

In October 2020 Beeple put up an image on Nifty Gateway of a snorting bull wrapped in the American flag, engulfed by a storm of dollar bills. It was called Politics Is Bullshit. A hundred copies were available, at a dollar each. As a further enticement to would-be purchasers, the artist had added his own explanation: “ok first off it’s a f***ing dollar, if you need extra convincing from some BS artist’s notes wether you want to spend a dollar on this i will punch you in the god damn face. smash the buy button ya jabroni.” We’re not talking Shakespeare here.

The army of jabronis did exactly as they were instructed. Beeple’s endollared bull began selling and reselling at an extraordinary lick. In December 2020 another of his offerings screamed its way to $500,000 — in five minutes! Today, if you want one of the 100 numbered NFTs of Politics Is Bullshit, and you’re lucky enough to locate an example, you’ll need to fork out a million dollars for it.

In the crypto jargon of NFTs, putting something up for sale on Nifty Gateway is called making “a drop”. But the true drop here is in human values and tangible common sense. Sitting at home in the twilight, punching mad noughts into a keyboard is archetypal Covid behaviour. In the dysfunctional conditions created by the virus, unreality has boomed.

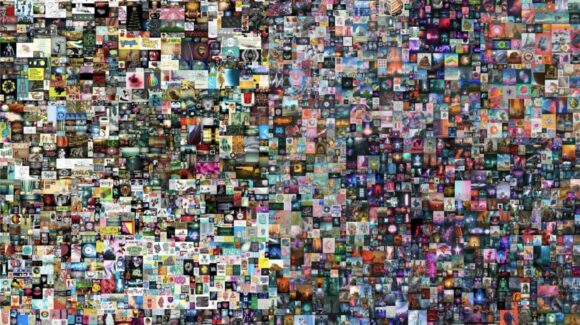

In March this year, Beeple’s magnum opus, called Everydays: The First 5000 Days, came up for auction at Christie’s in New York. It was a digital collage of everything he’d made since he began his daily output in May 2007. By chance, I was recording my podcast at the time, Waldy & Bendy’s Adventures in Art, and we decided to cover the sale, live.

Bendy is the art historian Bendor Grosvenor, who used to be a dealer. In the build-up, the two of us had squabbled gently about the price Everydays might fetch. Bendy suggested $3 million. I laughed. By the beginning of the week it had reached $2 million. A couple of days later it was up to $6 million. On the morning of the sale, as we went live, it spurted to $24 million. I was in shock. By the time the clock ran out on the auction, Everydays had soared to $69 million, which made it the third highest price ever paid for a living artist, beaten only by David Hockney and Jeff Koons.

As fate would have it, the following week we had Hockney on the podcast so I asked him what he thought of NFTs. “I call them ICSs,” he guffawed, “international crooks and swindlers.” Hockney makes digital art, too, but the images are then printed to make them tangible. His quip about ICS made its way into the international press, and eventually to Beeple himself. Taking to Twitter, the newly enmoneyed digital art tycoon responded with excellent sarcasm. He wanted, he said, to “go legit” and buy himself a printer. His budget, he whooped, was $69 million.

By this time the name of the Christie’s super-buyer had also emerged. He turned out to be an ethernet tycoon from Singapore who calls himself MetaKovan. MetaKovan’s plan was to build a virtual museum and fill it with the 5,000 Beeples. He’d already rehearsed the plan with 20 Beeple images he’d bought earlier and inserted into a virtual museum called the B20. Visitors to the virtual museum could buy shares in it. The shares started out at under $2 a pop. By the week of the Christie’s sale, they had risen to $28.

Thus invigorated, a ragbag of crypto explorers began circling the NFT money tree. The co-founder of Twitter, Jack Dorsey, sold his first tweet as an NFT for $2.9 million. Mick Jagger announced that his new song, Eazy Sleazy, was going to be available as a charity Nifty. In February Trevor Jones set a new record for the most expensive NFT edition by selling 4,157 copies of his painting Bitcoin Angel — Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa with a giant bitcoin in the background — for $777 each. It took seven minutes. You do the maths.

It couldn’t last. All over the art press puzzled writers began worrying about scams and bubbles. A careful trawl through Beeple’s 5,000 Everydays revealed a smattering of images that were deemed racist and homophobic.

Serious concerns were growing as well about the environmental impact of the Nifty craze. Crypto technology leaves huge carbon footprints. NFTs gorge on electricity. A French artist called Joanie Lemercier, who had built a reputation as an enemy of carbon emissions, “dropped” six new examples on Nifty Gateway and watched them soar to tens of thousands of dollars. Only later did he work out that the instant sale had consumed the same amount of energy as working in his studio for two years.

A Dutch economist called Alex de Vries, founder of the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index, estimated that by late 2017 the bitcoin network was using up 30 terawatt hours of power a year — the same as the Republic of Ireland. Right now, he estimates, it’s three times more: about the same as Norway. The cryptocurrency ethereum, with which MetaKovan paid for his record-breaking Beeple, needs as much energy to run as the whole of Libya.

These are terrible figures. They add hefty baggage to a declining situation. Bad art, bad politics, bad environmental impact — things are not looking good for the NFT. It’s clear as crystal the bubble will pop. The question is when.