French symbolism is a difficult art movement to take seriously. Chief among its problems was an uncontrollable urge to head over the top. Whatever was needed, symbolism delivered too much of it.

Then there was the anachronism. The 20th century was but a step away — steam trains were crossing the land, factories were belching smoke into the sky, Eiffel was building towers of iron — yet here was symbolism dreaming of Oedipus meeting the Sphinx and Hercules fighting the Hydra. Reason’s brakes were being slammed; time was being put into reverse.

The embodiment of this decadent onanism was Gustave Moreau (1826-98). Born into money in Paris, indulged by generous parents, Moreau was a sickly eccentric with a whiff of darkness about him. If you watched the engrossing French police series Spiral you will already have seen his work because the paedophile in series one chats up young girls in the Gustave Moreau Museum in Paris. An evil paedophile and Gustave Moreau — it’s a convincing union.

So I approached the rare offering of Moreau that is being served up at Waddesdon Manor, the Buckinghamshire home of the Rothschilds, with a morsel of trepidation. Waddesdon is gorgeous, an engrossing and uplifting day out. But as a French fantasy château in the middle of Buckinghamshire, it, too, wages a mini-war on reason. Add to that the fact that the Moreau art being shown here illustrates the fables of Jean de La Fontaine — The Tortoise and the Hare, The Goose That Laid the Golden Eggs and all that — and you have the potential for disquiet.

It’s a small show. Just a single room lined with the 35 watercolours that remain from a big commission in 1879 to picture the whole of La Fontaine’s enduring mix of folkish subjects and precision moralising. Acquired by the Rothschilds early in the 20th century, there were originally 64 of these madcap imaginings, but half of them disappeared in the Nazi era. The surviving watercolours have not been seen in public since 1906.

La Fontaine’s Fables are famous because they jump the fence between innocence and experience. You read them to kids, but their lessons guide you as an adult. Before Moreau had his go, his artistic predecessors tended to favour the innocent side of the fence, with cute animals and an air of rural wisdom. That is not what you get here.

Instead the stories are magic-carpeted far away from the French countryside to a fabulous magic land adjacent to the place where the One Thousand and One Nights are set. If Moreau’s art were a box of chocolates (hey, this is a symbolism review!) it would be something rich and squelchy: dark chocolate cherry liqueur creams, perhaps, or rosehip and raspberry gin truffles. The centres would be soft and the flavours complex.

The first image we see is an allegory of Fable herself, flying across the sky on the back of a hippogriff — a mythical creature that is half-horse, half-griffin. Naked, pensive, elegantly riding side-saddle, Fable has the mask of Comedy on one shoulder and the whip of Satire in her hand. Her hippogriff’s wings are a blue so intense they would shame a sunlit peacock. And what is that crazy blue bird with the fairy tufts showing her the way? One image in and already La Fontaine’s Fables have had the kitchen sink thrown at them.

“Wow,” I gulped.

A couple of images later we’re in some sort of lost mountain kingdom, a land of peaks and lakes not unlike the mysterious background of the Mona Lisa. At the centre of this soaring landscape an angry dragon with more tails than an octopus has legs has crashed through a fence and is about to chew up a handsome fellow in golden armour hiding in a tree. In the distance another dragon, this time with many heads, is stuck in the same fence. The story here, The Dragon with Many Heads and the Dragon with Many Tails, contrasts the effective violence of the many-tailed dragon with the ineffective thoughtfulness of the many-headed one. It’s a tale of warfare, with the moral, I suppose, that action speaks louder than words.

“Wow,” I gulped. Has a tiny watercolour ever felt as huge as this? And look how tangibly anxious is the thimble-sized guy in the tree.

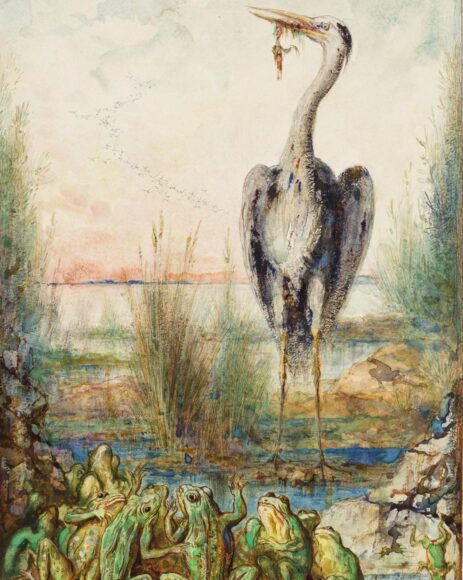

The Frogs Who Ask for a King tells of some frogs who are bored by democracy and want Jupiter to give them a king. So he sends them a log that floats in the water and does nothing. “We want another king,” they croak. So he sends them a heron. And there they are, huddled in fear on the riverbank, while the heron chews on the remains of another tasty amphibian.

“Wow,” I gulped at the cruel charm of it all. Be careful what you wish for.

The gulping continued for the entire circuit. Straining every creative sinew, Moreau succeeds, again and again, in extending what is possible with watercolours. It’s a cliché to describe a painting as jewel-like, but that is what we keep getting: blues that throb like powdered sapphires, reds that glow like rubies, gold that gleams like an Australian nugget. An entire medium is being transformed.

He also complicates the presence of La Fontaine, forcing the stories deeper and deeper into the viewer. The Cat Transformed into a Woman is the tale of a man who falls in love with his cat and manages “by dint of prayer, and charm, and spell” to turn her into a woman. After a night of furious lovemaking she suddenly jumps out of bed and chases a mouse across the room. Moreau shows her about to pounce, while the poor guy in the bed hugs his pillow like a child watching a horror movie.

“Wow,” I gulped. That’s creepy.

Beautifully observed animals keep popping up. A screaming monkey rides on the back of a speeding dolphin. An elephant is frightened by a mouse. To sharpen his accuracy, Moreau became an obsessive visitor to Paris’s famous urban zoo in the Jardin des Plantes. Rats keep figuring as well, a reminder, mutters the catalogue darkly, of the harsh realities of the siege of Paris in 1870-71, when the citizens were forced to eat whatever protein they could catch.

It isn’t only the moods that keep shifting. So do the environments. One moment we are on the banks of a quiet pond, watching the frogs, the next we are fleeing from pterodactyl-like dragons in the fabulous kingdom of Kubla Khan. One interior looks like a Mogul palace. Another like a woodcutter’s hovel.

It makes for genuinely exciting viewing. And the recognition grows inexorably that this is a remarkable body of work: probably Moreau’s masterpiece.

Gustave Moreau at Waddesdon Manor, Bucks, until Oct 17