There are several reasons why the Rodin show at Tate Modern feels awkward. First, there is the question of dates. Rodin was born in 1840 and died in 1917. So when the dial clicked over from the 19th century to the 20th, he was 60, an ageing Victorian whose career poked into the modern age like the tip of an iceberg. At Tate Modern, where the contemporaneity smells as sharply as skunk, he doesn’t look at home.

There is also the issue of his machismo. Rodin was a serial mistreater of women. Tate Modern, meanwhile, has cast itself firmly and loudly on the distaff side of art history in recent years. The arrival of the priapic Rodin in these revisionist atmospheres has an air of trespass about it.

The gallery is clearly aware of the clash of moods because the pale and fidgety event its alchemists have concocted for us is trying to frame a different Rodin: one who’s been demythologised, de-testosteroned, yanked up to date. The bomb squad has been called in, and it’s left behind a slighter presence: Rodin defused.

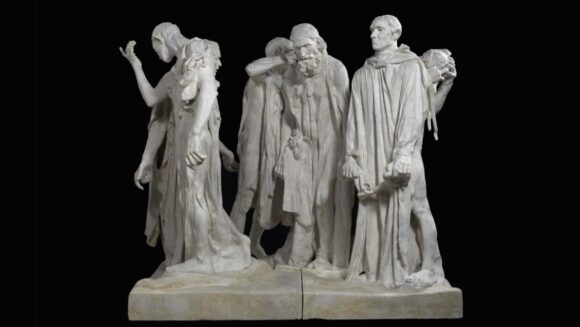

We catch up with him in 1900, when he mounts a self-funded retrospective in a jerry-built pavilion in Paris and fills it, not with obviously finished work — the famous bronzes, the big marble carvings — but with a quivering crowd of plaster casts.

At the time casts were seen as an intermediate stage between clay originals and finished bronzes: humble things. Their ubiquitous presence in museums and art schools, where they served as much-hated teaching aids, imbued them with the lowly air of copies. For Rodin to confine his big retrospective to plasters was a confrontational step.

In the photographic blow-ups of the 1900 show included here, it looks like an art-filled barn in an episode of Salvage Hunters. What a mess. Hundreds of sculptures, of various sizes, arranged high and low, on floors and pedestals. The Thinker here. The Kiss there. Bits of both of them poking out from behind other bits. In his self-mounted retrospective Rodin was after an atmosphere of fertility, freedom and flux.

When long-living artists enter their final decades they almost invariably loosen up and start working more quickly. Making art becomes a race against time. And because they have been there, done that, bought the smock, they care less about existing rules and prefer, instead, to make up new ones. It’s what art historians call a late style.

That’s what we get here. Taking its cue from the display in Paris, the Tate’s effort focuses on Rodin’s many, many plaster casts, with tiny detours into drawings and bronzes. The idea is to present him as a questing, inventive, itchy artist, who passed most of his career in the 19th century but whose creative spirit belongs in the 20th. Rodin, says this hopeful storyline, was a modernist manqué.

To make the point, the journey starts with its only bronze, a beautiful life-size nude of a man with his arms up known as The Age of Bronze. Originally, when he was made in 1877, he held a spear in his left hand and would have been easier to recognise as a Spartan warrior. Indeed, the model for the sculpture was actually a Belgian soldier called Auguste Ney. But by removing the spear, Rodin undated his classical hero and took away his military purpose, leaving behind an ambiguous nude whose movements make no obvious sense.

It’s a strategy he was to use increasingly in the plaster casts, freeing them from specific meanings. The Age of Bronze has been included because it is seen as pivotal. The musculature and anatomy in the work were so convincing that some critics accused him of passing off a life-cast as a sculpture. According to the exhibition paperwork, Rodin was enraged by these accusations and, from then on, decided to make his contribution unmissable with distortions, enlargements, dissections and amputations. Hence the writhing plaster casts.

It’s a nice story. My own feeling is that it was the stuff found in the teaching cupboards of the École des Beaux Arts that really inspired him. The bits of arm, the beheaded torsos, the strange combinations of limbs, the sense of mess, the sense of fragment — everything you see in the crowds of plaster that pack this show can also be found in the basements of the Louvre, where the Venuses de Milo have been chucked in with the Apollo Belvederes.

Whatever prompted the revolution, there is no doubt that his sculpture develops peculiar ambitions. The central room at the Tate has a busy selection of his best-known works in plaster, mounted on a raised wooden dais that is trying to evoke 19th-century floorboards, I imagine.

The Thinker is there in a brooding giant version. So is a mini-Thinkerperched cheekily on a pedestal. Various preparatory models for the great rejected Balzac present him in pieces, naked, headless and even as an empty dressing gown waiting for a body. The giant foot on a pedestal is The Thinker’s foot. The strange head pressed against a wall is The Thinker’s head. The famous Walking Man, a torso with legs, armless, decapitated, strides towards us like the unstoppable corpse of a zombie.

It’s restless, searching, bellicose stuff, entirely devoid of elegance or grace. Rodin, in his late years, comes at you with predatory energy, like one of those angry boxers who only ever go forwards. By showing only the plaster casts made from his original clay models, the display gets you as close to his creative moment as it is possible to get. The ambition is clearly to mimic the fertility and freedom of the 1900 retrospective,but the clean, white atmospheres of Tate Modern are the wrong background for pugilistic energy, and it’s an uneasy union.

Beyond the set-piece central space, the journey grows more confusing. As Rodin steps up his experimental doodling — mutilating bodies, repositioning limbs, taking a bit of sculpture here to finish a bit of sculpture there — the plaster casts grow weirder and more numerous. It becomes increasingly difficult to sense a direction in them. Although the show is divided into clusters, they grow quickly samey, and as each step blurs into the next the only quality that keeps standing out is the agitation. There will be boxes filled with worms that do not writhe and squiggle as relentlessly as this event.

It’s an impression exaggerated by the reliance on plaster models, with their restless surfaces and temporary spirit. It means the best moments in the journey occur, not when Rodin’s fragments are buzzing before you like bees, but when they settle long enough to form something monumental and still.

The giant brooding Thinker, several times life-size, is one such moment. Another is a row of heads, made in 1910, of a female Japanese model called Hanako who finally stills his hand and persuades it to enjoy a moment of repose.

The Making of Rodin, Tate Modern, London SE1, from Tue until Nov 21