Stepping into an art gallery after the interminable months of screen-watching was more slap than hug. There was a sense of having to learn something afresh, like trying on new shoes or feeling your teeth after a visit to the hygienist.

Those critics who have been making hay during the lockdown — readers of novels, watchers of TV, listeners to records, radios and podcasts — will have little to notice when they get out of the house. But we sailors on the choppy waters of art can feel the glorious spray of awakening in our faces!

The show itself was a curious event: a cross-generational double bill of Frank Auerbach and Tony Bevan, two artists who appear from some angles to have much in common, but from others to be strikingly different. Auerbach you know about. There are those who proclaim him to be the greatest living painter, and you’ll get little argument from me on that score. Born in Berlin in 1931 to Jewish parents, forced to flee to England, his past locks him into the big darknesses of European history. He is a survivor, and the unwavering faith in oil paints he has exhibited gives his work a heroic aura.

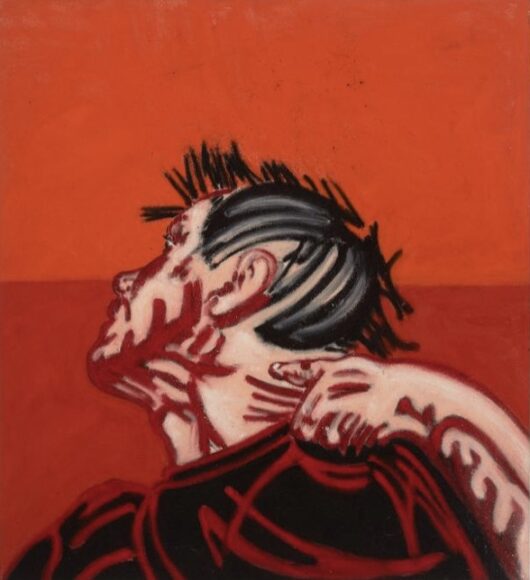

Compared with him, most artists look lightweight. But not Bevan. Born in Bradford in 1951, he, too, is a figure painter who has never left his lane and displays an excellent firmness of purpose. There’s something working class and Yorkshire about his doggedness. His art, though, feels younger, brighter, edgier. Its tonalities are postwar, Auerbach’s prewar.

Uniting them here is a shared obsession with the human head. Both artists have spent most of their careers dealing with it. Auerbach has painted and repainted a narrow range of female models, while Bevan looks mostly at himself. The show has divided 20 or so of their paintings into loose pairings and encourages us to look first at one, then the other.

Putting two artists in one show can have various consequences. In this case it leads to an irresistible desire to compare them. Although both deal exclusively with human heads, neither can fairly be described as a portraitist. Indeed, one of the surprises here is how firmly the show makes clear it is not concerned with likenesses. Auerbach may give his sitters names and initials, but who they are feels irrelevant. The search here is for the stuff under the likeness — the structure of a head, the dynamics of an expression.

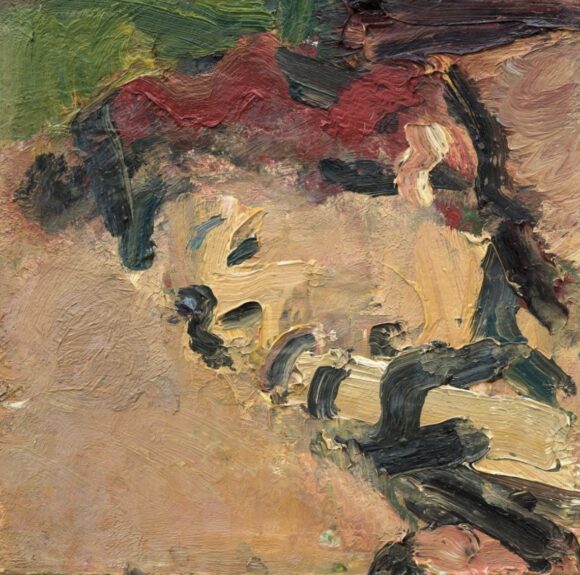

Because the comparisons are so intimate — Auerbach and Bevan, side by side — their differences are made extra clear. I’ve seen a lot of Auerbach in my time — his presence has been as consistent and lengthy as the Duke of Edinburgh’s — but never previously has it been as obvious as this that he is basically a cubist: reducing the head to its basic forms and planes, reassembling it with paint and palette knife. His search is for perfect encapsulation. But because it’s done with oils — wild and splashy, wet and drippy, loose and nimble — it’s easy to mistake it for expressionism.

Julia Sleeping, a gorgeous splodgy thing in dark pinks and blacks, enlivened by a sudden mop of red and green, feels abstract from a distance. Only when you get close do you fully recognise the sleeping Julia: her closed eyes, her puckered mouth, the face buried in the pillow. Achieving such exquisite precision with a fine nib is one thing. Achieving it with slabs of oil paint an inch wide is another.

It’s something I’d forgotten: nothing on the studio shelf beats the juicy, slippery, drunken excitement of oil paints. They connect magically with the nerve ends, and in my case with the tongue. For me, enjoying Auerbach is an experience that is as close to licking as it is to seeing.

Bevan’s chosen medium, acrylics, are another matter. Acrylic effects are desiccated and powdery. If oil paints are the gateau then acrylics are the dry biscuit. To compensate, Bevan crusts his surfaces with thick moonscapes of pure colour — poppy reds and daffodil yellows; Madonna blues and purples of the night.

Set against these zingy backgrounds, the isolated heads he presents — the self-portraits — have the air of specimens about them. They adopt fierce expressions in the manner of Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. They twist their necks and extend them as if to show us something. The surfaces are bone dry, but the moods are sweaty, nervy, anxious.

Oil paints v acrylics; looking in v looking out; art that speaks to the tongue v art that speaks to an itchy skin — hello, galleries, we’ve missed you.

Frank Auerbach/Tony Bevan, Ben Brown Fine Arts, London W1, until April 30