Right now the trendiest thing to be in art is a collective. Everybody’s at it. All around the international art world collectives are springing up like crocuses on a springtime lawn. It’s as if nobody wants to be just them any more. Everybody wants to be part of something else.

Here in Britain we saw early evidence of the urge and its issues in 2015, when the architectural collective Assemble won the Turner prize. Assemble is a loose gathering of a dozen or so architects and designers who transform old buildings: reclaim them, rebuild them. They are, without question, a good thing. What they are not is artists. Even the Assemble members were flabbergasted by their victory.

The last time the Turner prize was held, in 2019, the gong that went wrong was at it again, throwing itself in front of the cameras like kids behind a newsreader. Instead of having a single winner, the four shortlisted artists formed an impromptu collective and insisted all four of them receive a share of the prize. They didn’t like the rules. So they changed them.

It’s pretty clear, therefore, that collectives are an alcohol-free source of Dutch courage. People who would never do something on their own find the confidence to do it when they are in a gang. It’s true of the Crips and the Bloods in South Central, Los Angeles. It’s true of the thinly talented foursome on the shortlist for the 2019 Turner prize.

This urge to collectivise is set to plant its biggest footprint yet on contemporary art at the next Kassel Documenta, planned for 2022. Every five years the unglamorous city of Kassel in central Germany hosts an international mega-exhibition that bills itself as “a museum of 100 days”. Started in 1955 to bring aesthetic solace to a broken Germany, Documenta used to be a really good thing. Then it all went a bit Animal Farm.

The show was always political, but the politics used to be visceral: a tad mad, a tad weird, delivered a tad crazily by Joseph Beuys and the like. I stopped going several efforts back, when I could no longer face spending all afternoon in the dark being lectured by artworks that felt like speeches at a council meeting, and often lasted longer. At the last Documenta I visited, I worked out it would take me 37 days to see all the video art on offer, and that was without sleeping.

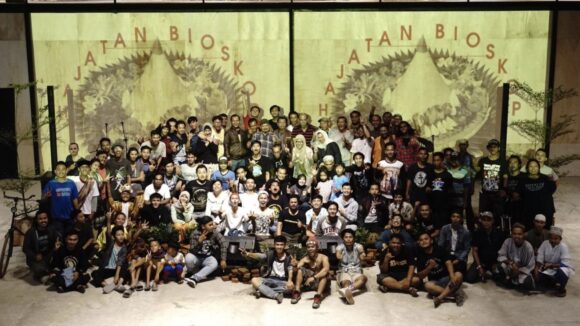

The event is usually overseen by a single curator, but for Documenta 15 the parcel has been passed to a collective from Indonesia called ruangrupa. Based in Jakarta and consisting of artists, architects, social engineers and poets, ruangrupa — who demand to remain democratically lower-cased because they don’t believe in hierarchies — have chosen as their exhibition theme: lumbung.

Lumbung is Indonesian for a rice barn. In traditional Indonesian villages rice is stored collectively in wooden huts and then shared. Thus the ruangrupa collective has made collectivity itself its collective concern. And its members have at their disposal $50 million or so, granted to them by the state authorities in Kassel, to make their theme sing.

They began by asking nine other collectives from Spain, Palestine, Mali, Indonesia, Colombia, Hungary and Germany to join them at Documenta 15. There was also one from Denmark, but that had to close because of Covid. Now five more have been added from Bangladesh, Cuba, New Zealand, Kenya and — get the trumpets out — Britain, where we will be represented by Project Art Works, from Hastings, a collective of which I was not previously aware.

By the time it opens in June 2022, Documenta 15 will, with absolute certainty, have broken the world record for having the most collectives at work simultaneously in one city. As a display of shared creative participation it will have no precedent. Why then does the heart slump so precipitously at the prospect?

Chiefly, I think, because the arrival of all those committees at once will lead to many things, but encapsulation is not one of them. Art collectives don’t encapsulate. They extend. They don’t narrow. They enlarge. They don’t do brilliant or imaginative or visceral. And they certainly don’t quicken the pulse. So what do they do?

To get a sense of what ruangrupa’s Documenta will be like, I have spent the past two days logged on to the internet, pretty much full-time, trying to find some art by them. There isn’t any. Nothing tangible at least. What there is — and there’s tons of it — is talking.

Ruangrupa at conferences. Ruangrupa at biennales. Ruangrupa indulging in a practice they refer to clunkily as “hanging out”: lots of people sitting around on bean bags saying things. Ruangrupa lecturing us on our ethics. Ruangrupa complaining about colonialism, capitalism and patriarchy. Where there’s a microphone, there’s a ruangrupa spokesman.

This world-class ability to talk endlessly about the way we need to change the world flies in the face of the idea that a picture is worth a thousand words. In ruangrupa’s universe, a thousand words is just a chapter heading.

Pretty much everything they do requires enormous slabs of time to be devoted to it. They organise meetings and performances. They mount paper-heavy installations and packed displays of archive. They’re super-keen, of course, on that greedy eater of hours — audience participation. Sometimes they put on a music event, and a Thai punk band will pop up on screen. Usually it’s just more bits of paper and more talk.

Why and when did art get saddled with all this wind-baggery? When it stopped describing the world as it was, and started trying to save it. Ruangrupa are well-meaning enough. They want to make everything better. But by saddling art with that responsibility, they’re putting howdahs on a gazelle.

Imagine a world where it takes ten people to write a poem, and 50 people to write a book. Where everything is a chorus from Aida and nothing is Maria Callas singing L’amour est un oiseau rebelle from Carmen. Where the delicacy and specificity of a painting by Gwen John is replaced by a Zoom meeting with 100 people on the subject of middle-aged female loneliness.

No thanks.