The collecting spirit is a savage impulse. Behavioural scientists will no doubt have traced it back to its prehistoric roots and the need to possess every blue stone outside the cave, or a feather from every bird flying across the Miocene sky. Something like that.

My own battles with it also started early. As a kid I collected all the usual things. I did stamps, coins, Dinky cars, Marvel comics, football cards and, I regret to admit, birds’ eggs. At the time it was still legal, and I was an adolescent know-nothing who hadn’t listened keenly enough in biology classes. Later I began collecting old master paintings reproduced in Knowledge magazine. That turned into a frenzy for art history. So yes, I know about the collecting impulse.

The Great Lockdown has triggered all sorts of primitive reactions in us hominids, from the urge to hunt and gather whatever snacks are lying around the kitchen to the happy decision to let our hair grow however long it wants. However, the most expensive and derailing of these Miocene roll-backs has been the unleashing of our predatory collecting hungers.

Squirrelled away in our dark lockdown caves, armed with secret little password-chants that allow us to turn on our magic abracadabra machines, there we all are, surfing gaily about the universe, collecting stuff. For the wiser among us it’s just a case of stockpiling toilet paper and bin bags, brought to us by the sacred delivery divinity, Amazon. But for the wild ones, the crazies and no-brains with more money than sense, it’s a hunger for logging on to auction sites and paying way over the odds for pigs in pokes.

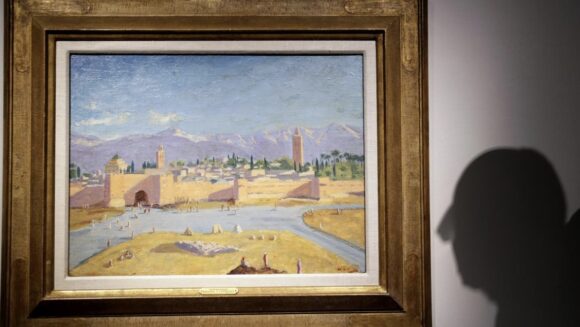

Recent weeks have seen some classic displays of the syndrome. The most astounding was the sudden splurging of $11.5 million on a daub by Winston Churchill of the view from his balcony in Morocco in 1943. “Daub” is Churchill’s own word for his art, not mine, although I agree with him wholeheartedly. He took up painting late in life to help him to relax and keep the “black dog” at bay. And he reached a decent amateur level.

If you saw his sunset view of the Koutoubia mosque in a car boot sale, you’d be pleased to spend a pony on it. At auction, if someone else had painted it, it might have gone for two or three tons. A monkey, tops. But this is the Lockdown, when values are scrambled and sense goes Awol. So it soared to $11.5 million.

Also on sale that night was a gorgeous drawing by Vincent van Gogh of La Mousmé, a French girl from Arles pretending to be Pierre Loti’s Madame Chrysanthème. It did well enough, rising to $10.4 million. But not as well as the Churchill.

The Morocco daub had three things going for it. First, it was painted at a particularly significant moment in the Second World War when Churchill and Roosevelt met in Casablanca to plot the downfall of the Axis powers. Second, Churchill gave it to Roosevelt as a gift, having knocked it off one evening from the balcony of his villa in Marrakesh. Third, and probably most importantly, the owner who put it up for auction was Angelina Jolie, who had been given it by her former husband Brad Pitt as a present. When you bought the Moroccan Churchill, you weren’t just buying art. You were buying a holy relic touched by two of the biggest saints in Hollywood.

If the collecting madness had stopped with the sun setting over Marrakesh it would have been just another grim week for the art spirit. But it didn’t. Also exploding into our consciousness last week was the sick and extraordinary rise of NFTs, or Nifties as I believe they are colloquially known. And, in particular, the sudden appearance among us of a king among the Nifty Grabbers, a middle-aged geek from South Carolina known as Beeple.

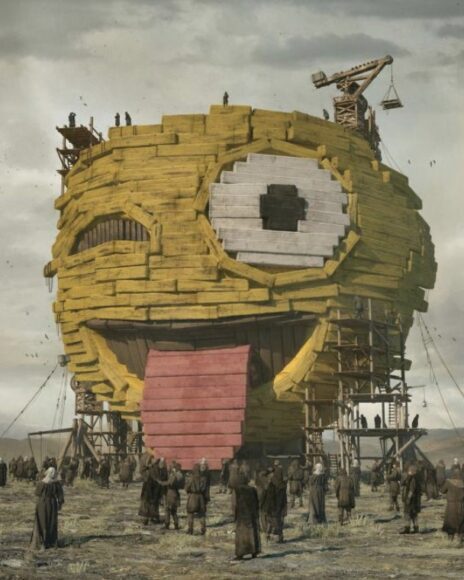

Beeple’s real name is Mike Winkelmann, but you can’t be a convincing ether bandit and hot-shot spawner of computer graphics if your name is Mike Winkelmann, so Beeple he became. A few months ago he decided to put some of his artworks up for sale on an auction site called Nifty Gateway. And quickly sold the lot for $3.5 million. This week he has been selling his magnum opus, a collection of 5,000 digital images rolled into one work, at Christie’s. When I first looked, the day after nurses were offered a pay rise of 1 per cent, the bidding for the big Christie’s Beeple was at $5.3 million. It’s now $9.75 million.

Essentially, he’s a sci-fi illustrator. A cheeky one. Using top of the range computer drawing technology, he dashes off a daily image of monsters battling with androids or giant monkeys turning into Donald Trump. It’s occasionally amusing, reliably superficial, mildly post-apocalyptic and seriously collectible. Other geeks, stuck in dark man-caves during the lockdown, have been falling over themselves to outbid each other. What’s made it all easier, and even more madly desirable, has been the rise of the NFT, or non-fungible token.

Nifties are a way of owning a digital image. It’s done with a piece of computer magic called a blockchain, which ensures that you, and you alone, are the official possessor of the thing in question. Everyone can see the Beeple android or the exploding blob. But only you can own it.

Yes, collector, it can be yours, yours, yours. But for that to happen you need to pay, pay, pay. It will cost more, more, more. Till the bubble goes pop.

Beeple’s Everydays sold at the Christie’s auction for $69.3 million.