The words of Kirk Douglas barrelled into my thoughts the other day. And no, it wasn’t anything to do with his Oscar-nominated portrayal of Van Gogh in Lust for Life, memorable though that was. Rather, I was thinking of my one and only visit to Palm Springs and a tour I made of the local museum.

On show was a selection of modern art lent by Hollywood moguls and famous film stars. Leading you round it was an audio guide voiced by Douglas. When we reached a Kandinsky, a pulsing abstract from about 1912, Kirk reached inside himself for something profound and announced: “Kandinsky was the painter who took the subject matter out of art.”

It was a very Palm Springs definition of abstraction, and I, of course, guffawed unworthily. Yet remembering it today, what really hits home is not how clumsily Douglas described Kandinsky’s famous achievement, but how wrong he was about it. We now know that Kandinsky was not the first abstract artist. Not by a long way.

It’s one of the points I expect to be emphasised by Women in Abstraction, an exciting-sounding event that is due to open in May at the Pompidou Centre in Paris — Covid willing. If it does happen, what we will be seeing is an energetic attack on the masculinist timeline of modern art that presents Kandinsky as the first abstract artist, followed quickly by Malevich, Mondrian et al.

It’s the timeline I was taught at university, what we can call “the MoMA version”, laid down by the Museum of Modern Art in New York in the 1930s and stuck to firmly ever since. It’s in all the books. And it’s the sequence that was insisted on before any of us had heard of Hilma af Klint or Barbara Honywood or Anna Howitt Watts or Georgiana Houghton.

The past couple of decades have seen a comprehensive reunderstanding of art by feminist historians. Not only has the MoMA timeline been challenged, but so have most of the tonalities that went with it. Looking afresh at the emergence of abstract art, recent art history has discovered a multitude of female pioneers, and especially the weird and fascinating af Klint.

Born in Sweden in 1862, af Klint was painting abstract pictures by 1906 — half a decade before Kandinsky. In 2018 the Guggenheim in New York mounted a tribute to her that became the most popular exhibition in the museum’s history, with 600,000 visitors ascending the Guggenheim spiral to commune with Hilma.

Among the things they were keenest to see were the large abstracts produced between 1906 and 1915 for a sacred space known as the Temple. Filled with gentle cosmic swirlings and spooky staircases of coloured geometry, they are af Klint’s most mysterious and unknowable paintings. Huge, lyrical, otherworldly — nothing previously encountered in art looked like these. “Wow,” we exclaimed when we saw them and read their dates. Where have these been hiding?

In Stockholm, it turned out. Before her death in 1944 af Klint left a will stating that her abstract art should not be displayed publicly for 20 years. We failed to discover her because she didn’t want us to. It was only when her nephew — to whom she had left all her work — donated it to a foundation set up to promote her art that she began, finally, to claim an audience.

Also at work here, though, was a hardened art historical prejudice against esoteric adventuring and the paranormal. Af Klint was a spiritualist. Her interest in the world beyond was triggered by theosophy, the contentious pseudo-religion founded in the 19th century by the spooky Madame Blavatsky. Theosophy’s largely uncredited impact on modern art is one of the big takeaways of the new art history.

Af Klint’s interest in Blavatsky led her into the orbit of the High Masters, a cluster of cloudy divinities who were waiting to be worshipped at the Temple, the sacred location for which she painted her abstract murals. The paintings were not really her work, she insisted. She was merely the conduit through which the High Masters were expressing themselves.

What’s interesting here, apart from the transparent kookiness of it all, is how the origins of af Klint’s unexpected abstraction appeared to disqualify her from the MoMA timeline. Even when her work came out of hiding, it was many decades before it was taken seriously as art rather than a cranky religious sign language.

Modernist thinking had always been fiercely reluctant to accept any esoteric understandings of art’s progress. It’s as if the tiniest acceptance of a religious or hermetic explanation for an artistic journey would somehow undermine the ambition of art to be seen as a serious topic of modernist study. Modernism wanted to come across as one thing: the kooks were revealing it to be something else.

The paradox here is that the artists who had been accepted into the modernist canon — Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian — were just as guilty of hocus-pocus. All three had dived into Blavatsky’s universal teachings. They weren’t quiet about it, either.

Kandinsky’s celebrated book Concerning the Spiritual in Art had made his theosophical leanings thoroughly obvious. Mondrian’s devotion to Blavatsky was so unshakable that a portrait of her was among the only possessions he had with him at his death. It wasn’t the artists who were hiding their spiritualist drives. It was the organisations that had taken custody of their reputations.

When MoMA mounted its big Mondrian retrospective in 1995, the painter’s early theosophist art was redacted clumsily from his journey. The Jackson Pollock retrospective that followed was happy to include the esoteric imagery and pseudo-mathematical calculations of his early symbolist paintings, but not once did it mention the theosophy that had prompted them and which he had begun studying in California in the 1930s. Wherever the paranormal popped up in modern art MoMA censored it.

It’s difficult to resist seeing a masculinist agenda in this conspicuous institutional scorn: big boys don’t cry, and they don’t believe in fairies. It’s certainly noticeable that when the power balance in art shifted towards the feminine, more room was quickly found in the canon for work with esoteric or spiritual leanings. Not only did af Klint appear to prefigure Kandinsky’s first experiments in abstraction, but a cluster of even earlier artists have now emerged to prefigure af Klint.

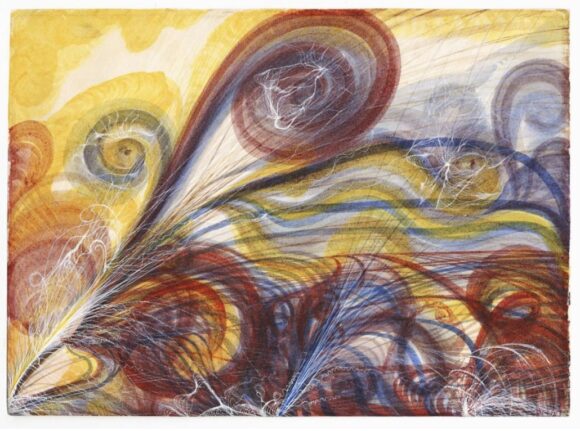

Britain in the 1860s, it turns out, was a hotspot of esoteric art experimentation. Barbara Honywood and Georgiana Houghton both made art during seances. Gathered around a nocturnal table with their planchettes and their ouija boards, they allowed the undead to take possession of their brushes and direct the creation of an abstract art of remarkable novelty. Houghton’s abstract watercolours from the 1860s predate Kandinsky’s first abstracted efforts by half a century.

This feminine focus on spiritual creativity has now gathered so much momentum that it is perhaps the leading world view in contemporary art. The Gwangju Biennale, which is due to open in South Korea in April under the guidance of two star curators from Europe, has as its stated aim the recognition and appreciation of native Korean beliefs and the influence of local shamans. “The need for learning from the wisdoms of indigenous cultures, Shamanic practices, matriarchal models of society is growing more than ever,” say the curators.

Turning the clock back to beliefs before modernity is an insistent feature as well of much of the art coming out of Africa. The re-creation of shamanistic customs and tribal traditions is regularly presented as a deliberate antidote to the methods and ideas of western colonists.

You cannot find a more au courant artistic presence than the ubiquitous South African photographer Zanele Muholi, whose fine retrospective at Tate Modern will reopen, with luck, on May 17. Muholi’s best work is a series of self-portraits in which she shows herself switching costumes and shifting identities like an energetic tribal mundunugu.

The methods of the colonists have repressed us, she seems to be saying. Let’s return to our own methods.