You know those scenes in action movies where a steel door is closing shut and the hero has to throw himself through a tiny gap at the last moment to escape? Well, that’s how it was with me and the Zanele Muholi retrospective that has finally opened at Tate Modern. It was ready to view a few weeks ago. But no sooner had I trodden softly round it than they announced a new lockdown. I got out with seconds to spare.

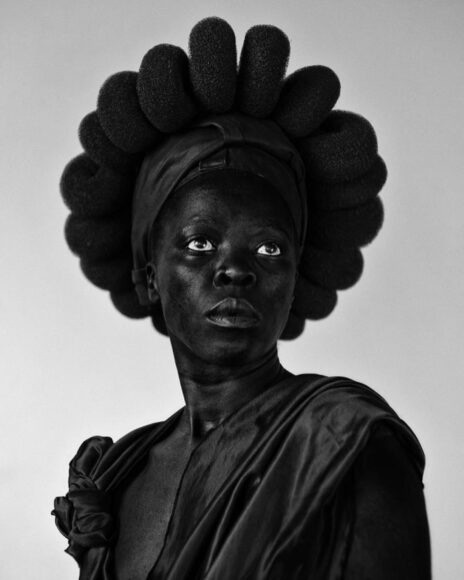

I first noticed Muholi’s work at the Venice Biennale last year. I suspect the same is true of the apparatchiks at Tate Modern. Basically, if your eyesight worked, you couldn’t miss it. Plastered about the Biennale’s biggest exhibition venue, the Arsenale, were gigantic blow-ups of a beautiful black face that towered over you. The captions told us they were self-portraits and that, interestingly, the artist had deliberately darkened their skin. This digital tinkering had the effect as well of making the eyes glow. In the gloom, the huge self-portraits hunted you down.

So the first thing to note about the Tate’s helpful retrospective is that it paints a strikingly different picture from the one in Venice. The career we encounter here has been misrepresented. This art isn’t mostly about Zanele Muholi. It’s mostly about everyone else. That is both its strength and its weakness.

Muholi was born in Umlazi, near Durban, in 1972. Like all South Africans at the time she was thrust into a situation of profound racial iniquity, where white bossed black, but black outnumbered white. Her father died soon after she was born. Her mother, Bester, who gets many namechecks in the show ahead, was a cleaner for a white family. So Zanele was brought up by relatives. As it veers off on its many tangents, this bendy event zigzags between activism and artistry, but what it seems always to be about is finding somewhere to belong.

Some of the uncertainty stopped when Muholi was 18 and Nelson Mandela was finally released from prison. However, other doubts came flooding in. In particular, issues of sexual identity began to preoccupy her.

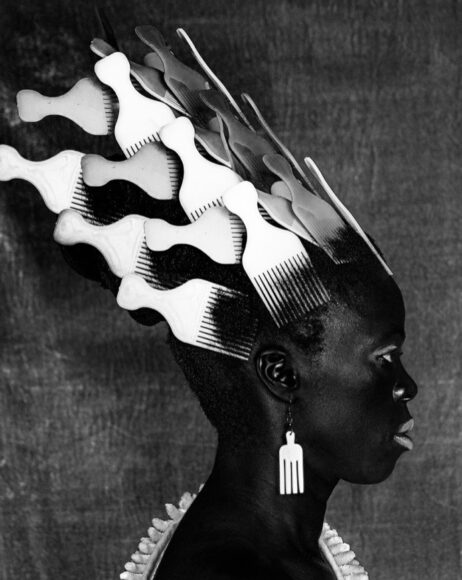

Muholi’s first career, we learn from an aside in one of the documentaries playing here, was as a hairdresser. In post-apartheid South Africa hair was a big cultural topic. In this show, too, it keeps popping up as a key concern. In 2003 she put down her scissors, picked up a camera, enrolled on a course in advanced photography at the Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg and strode off on a new journey.

The earliest photos here, taken in 2003-05, are some of her best and most memorable images. They come from a series called Only Half the Picture, whose ambition was to record the plight of the black lesbian community that Muholi had joined and which we see growing, so tangibly, into her extended family.

Among the most regrettable legacies of apartheid was the coarsening it prompted in all forms of human behaviour. For black lesbians it led to recurring episodes of “corrective rape”: violent sexual assaults by men with grotesque ambitions “to enforce heterosexuality”. Working in black and white, with a documentary precision that gives the photos the air of evidence in a trial, Muholi shows us the resulting scars.

Aftermath presents the lower half of a young woman, stripped to her pants, with a wound a foot long gouged into her thigh: her hands are clasped in front of her, as if to hide and protect her sex. ID Crisis watches a woman’s body being strapped in heavy bandages as she seeks, hopelessly, to obliterate the pendulous breasts that are her unwanted birthright.

You see the bodies, but not the faces. The captions explain they are missing because there was a need, for security reasons, to hide the identities of the victims. Yet presenting Only Half the Picture also prompts a level of imaginative involvement from the spectator that gives this early work such tender power.

Then something curious happens. For a large chunk of the show’s middle the tenderness and power disappear. Having discovered a lesbian family that welcomed and supported her, Muholi positions her art in its defence. Soon, sexual adventurers of every persuasion — queer, bi, trans, intersexual, asexual — enlarge the family. Muholi changes her pronoun from “she” to “they”. And a vision that had been intense and personal becomes communal and transparently political.

The series called Faces and Phases presents us with row after row of carefully staged portraits of a cast list that keeps growing. The captions stress that every portrait is a shared creation of the artist and the sitter. The “participants” chose what to wear and how to be represented. Thus the aesthetics of the yearbook drive the art.

Archive displays have become something of a cliché in contemporary creativity. Steve McQueen did something similar in the recent Tate show for which he photographed every Year 3 schoolkid in London and caused thousands of mothers to turn up at Tate Britain to find their child. As social politics, it’s a surefire hit. As art, it results in repetition and creative flatness.

Fortunately, Muholi’s retrospective saves its best moments for last. Having become a catalogue of South Africa’s marginals, the show transforms into something more subtle and imaginative when, once again, it turns into a vehicle for Muholi’s own preoccupations.

The final room is devoted to the self-portraits from the Venice Biennale: the ones with the darkened skin and whitened eyes. They come from a series called Somnyama Ngonyama, a phrase in isiZulu that translates as “hail the dark lioness”. The Tate, for some weirdly censorious reason, doesn’t give the translation.

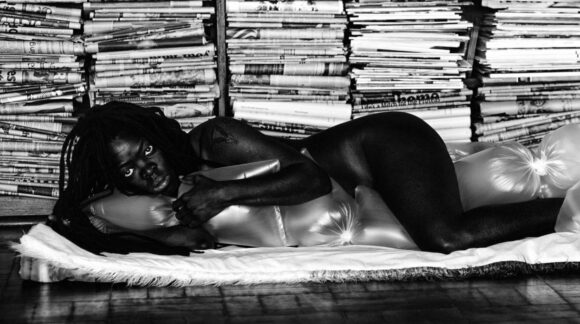

In these fierce self-portraits, Muholi dresses up in inventive homemade costumes to create a gripping gallery of new identities. What looks like a crown is a headpiece made of Brillo pads of the kind Bester used in her cleaning jobs. Another crown is made of safety pins. An attack on Muholi by scores of ghostly hands is achieved with a pack of inflated washing-up gloves. And that’s not a snake. It’s a vacuum hose.

Plenty of the skills on show here are those of a former hairdresser. There are echoes, too, of distant belief systems and natural magic. As for the lion in the title, most of these fabulous transformations of the quotidian into the magical, the domestic into the royal, the everyday into the supernatural, are anchored by the intense stare that tracks you around the room.

It’s exciting art: imaginative, memorable, transportive. And there’s an important lesson to be learnt from the fact that Muholi’s best work is found at the start and the end: when it is at its most personal.

Obviously, this event did not set out to prove that communality improves life and diminishes art. But that is what it does.

Zanele Muholi, Tate Modern, London SE1, until June 6