The Lone Ranger wears one. So does Zorro. And Spider-Man. And Captain America. Dammit, not only does Batman have one, but so does his sidekick Robin. And I haven’t even mentioned the Black Panther.

The fact is, you could not ask for a cooler cast of salvational heroes than our masked avengers. Time after time they save us. Again and again they preserve humanity. Yet still the regressively gened in our midst continue to babble that the mask is a blight on society, not a boon.

Perhaps we are seeing this backward doubting from the wrong angle. After all, in Japanese Noh theatre, the greatest actors are those who are able to express the most varied emotions by altering the tilt of their mask, or allowing it to catch the light differently. These are the masking skills we see recorded so precisely by the masters of the Japanese woodcut.

Maybe the whole point of the noisily expressed masking-doubt is to help us to identify contemporary cockwombles with immediate certainty? If we examine the best evidence we have of human patterning — the art we have made through the ages — what we see being proved recurrently is that masks are there to illuminate, not to conceal.

Maybe the whole point of the noisily expressed masking-doubt is to help us to identify contemporary cockwombles with immediate certainty? If we examine the best evidence we have of human patterning — the art we have made through the ages — what we see being proved recurrently is that masks are there to illuminate, not to conceal.

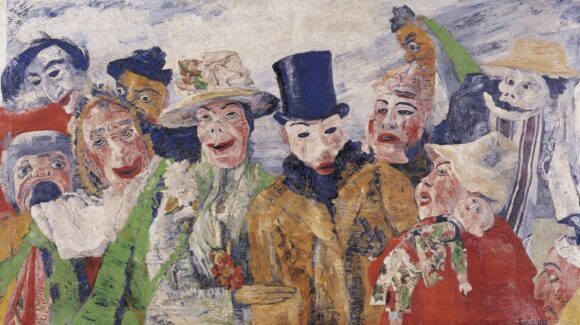

Why, as the 19th century turned into the 20th, did the Belgian expressionist James Ensor obsessively paint a ghastly cast of gurning and grimacing mask-wearers? Was he trying to disguise the stupidity and malice he saw in the world around him? Obviously not. Ensor painted the masks to make the malice unmissable. It’s what we might call the Masking Paradox: masks don’t hide, they reveal. It’s what artists love about them.

In the cave of the Trois-Frères in the Ariège in France, scratched on to the wall of the cavern, is a standing figure. They call him the Dancing Sorcerer because he seems to have been recorded in mid-move: a prehistoric contestant on Strictly, doing the lurch, lurch, lurch.

He’s probably an early representation of a human figure, but there’s room for doubt because he appears to be wearing an animal mask: half lion, half stag. As the cave in question was used for cultic rituals, the common view is that he’s a prehistoric shaman and that the animal mask is his identifier. Similar arguments swirl around the famous Lion Man, carved from a mammoth tusk in about 40,000BC and among the earliest-known sculptures.

The Egyptians wore masks. The Greeks wore masks. The Romans wore masks. Chinese art is busy with them. So is Indian art. And African art. There’s a show now at the British Museum celebrating the cultural history of the Arctic. Has it got masks in it? Of course it does. The urge to transform ourselves is universal and dates all the way back to the beginning.

Which is not to say that all mask donning is done for the same reason. Clearly it isn’t. The mask in art has myriad forms. The Elizabethan damsels who pop up in manuscripts and tapestries wearing round facemasks, called vizards, are doing it to protect their skin from the sun. Suntanned skin was the mark of the outdoor labourer, and if there was one thing the Elizabethan damsel did not want to be mistaken for it was one of the working classes.

The heyday of the mask in European art was, a tad perversely, the age of enlightenment. In science, politics, philosophy and literature, brilliant discoveries were being made. Yet beneath this finely educated surface, the human id, released from the tight supervision of the Renaissance, was running riot.

Walk into any French or Italian provincial museum, seek out the 17th and 18th centuries, and you are certain to encounter a woman holding a mask. They’ve been painted by Lorenzo Lippi or Jean-Marc Nattier or Felice Boscaretti, jobbing image-makers to the flirting classes whose names rarely appear in any serious chronicle of art. In a typical Nattier, a powdered rococo beauty, sheathed in shimmering silk, will dangle a dark mask from her fingers and invite immediate comparisons between the complexity of her expression and the plainness of her vizard. It’s a hilarious speciality.

An English painter called Henry Robert Morland produced the dodgiest masterpiece in the genre with a picture that hangs at Temple Newsam House in Yorkshire called The Fair Nun Unmasked. It illustrates Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock where the beautiful but fiercely Catholic Belinda attends a masque at Hampton Court and has a lock of her hair cut off by the besotted Baron. With her low-cut dress, a jewelled cross on her breast and a seductive mask in her hand, Morland’s Belinda is the least likely nun in global art.

From medieval mystery plays to Elizabethan vizards to the erotic fantasies of the rococo, Britain has always welcomed the mask. But we have never welcomed them as eagerly as the Italians: especially the Venetians. Porca miseria, but the Venetians love masks.

If you’ve been there, you will know what I mean. Masks everywhere. The one with the hooked beak and the sinister spectacles, that’s the Plague Doctor who presided over the Black Death and who has made a spectacular comeback in the video game Assassin’s Creed. The white mask with the gold trimming, that’s Pulcinella, the wiley hunchback from the Commedia dell’Arte, whom Domenico Tiepolo painted causing havoc all over 18th-century Venice.

That’s also the Venice — Casanova’s Venice — in which the game of love grew so heart-poundingly energetic that it threatened to sink La Serenissima. The revealing dress Belinda wears in The Fair Nun Unmasked is an example of a fashion called “décolleté alla veneziana” that swept furiously across Enlightenment Europe.

The dress was made of a light fabric that was basically see-through. In Venice, a make-up of carmine red was also applied to the nipples to make them more visible. And to top off the look — the cherry on the cake! — the signora in question would wear a velvet mask called a moretta.

Morettas were round and black. They had no straps or elastics to hold them in place. Instead, there was a small button sewn on to the back, which the woman gripped with her teeth. If you were wearing a moretta, you couldn’t actually talk. Seductions had to be conducted with a complex sign language involving hand gestures and fans.

When artists came to paint these morettas, they were faced with a circular black blob that looked from a distance like a large hole in the head. Pietro Longhi, the finest of the Venetian genre painters, had enormous fun turning the masks of Venice into something both comic and weird.

From the weirdness of the moretta it is but a tiny step to the spectacular and relentless weirdness of James Ensor. The whole point of a typical Ensor crowd, with its ghostly white faces and its rictus grins, is to reveal what’s usually hidden. Ensor despised what he saw around him. His ambition was to yank the horror into the open. And the best way to do that was with masks.