There are various reasons for putting artists from different epochs together in a show. The most common, and least glorious, is to double or triple your revenue stream. Thus fans of Monet, Whistler and Turner were able to flood jointly into Tate Britain when the objects of their affection had their fogs compared in a misty triple bill. It went so well that a few years later the Tate swapped Whistler for Twombly and did the same all over again.

So the first thing to say about the pairing of Tracey Emin and Edvard Munch that has opened at the Royal Academy is that it’s a genuine encounter. From the moment you step in to the moment you stumble out, you sense that mad Tracey from 1960s Margate and the Norwegian expressionist from the early days of the 20th century have been brought together by forces that are fierce and real. Both are strikingly unhappy. Both use the human nude to convey a humungous anxiety.

Not that it’s an equitable arrangement. Poor Munch feels as if he has been grabbed by the ear by Emin and frogmarched to the academy, then told to sit in the corner while she declares her passion for him. She dominates the acreage with new paintings. He pops up where he can with a smorgasbord of fragile watercolours and a spare selection of late works. It isn’t fair. But it is exciting.

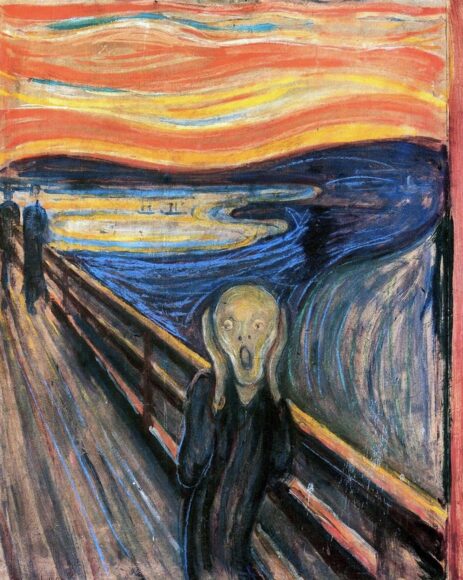

Munch is already a problematic presence. There’s a divide in his career between the early art — the art surrounding The Scream — which is intense and thrilling, and the late work, which goes on and on, and seems slack and sketchy. Early Munch good, late Munch bad, is the usual equation. That’s the opinion with which I arrived at this thunderous Anglo-Norwegian psychodrama, before the buffeting you get here persuaded me otherwise.

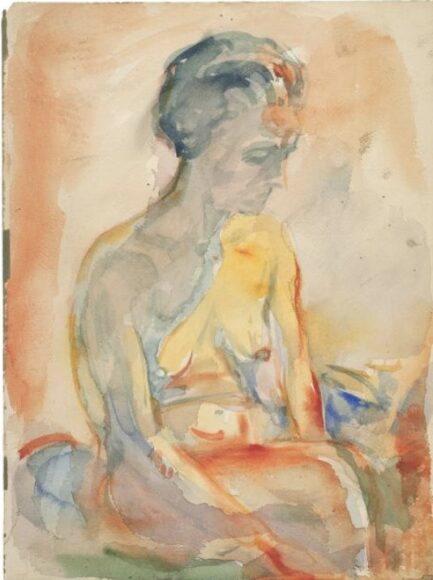

Munch’s confrontation with Emin achieves several things, but the one for which I am most grateful is that it opened my eyes to the potency of his late work. He became a quieter artist, that’s certain, but the scratchy, nervous, blotchy nudes that Emin has selected from the second half of his career form such an edgy harem. Bones showing, whiteness glistening, Munch’s shivering women desperately need a bowl of chicken soup.

That said, he has his work cut out getting a word in edgeways. The first thing you see, looming hugely across the opening vista, is a 6ft-tall close-up of Emin’s vagina emerging from an alpine blizzard of swirling brushstrokes that sometimes hide, and sometimes reveal. “Pay attention!” it screams.

The vagina picture belongs to Elton John. It’s clearly a response to the notorious Courbet of the same subject, his scarily intimate Origin of the World, past which even the bravest of us hurry when we visit the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. But where Courbet seems to creep in on a woman’s privacy, Emin thrusts her privacy straight at us. He peeps, she aims, in a noisy claiming of feminine territory that jangles the nerves at the best point for such a jangling: right at the start.

It could hardly be more direct. This is going to be a show about sex, love, the human figure, revelation and obliteration. And so it proves.

In the nude-fest ahead, no one wears any clothes. No one’s happy. No one relaxes. The only relationship that seems to be working is the one between Emin and Munch. But he has had no say in this active grabbing of hands across the ages.

Most of the big Emin paintings that dominate the journey feature reclining female bodies caught in intimate poses. And, of course, there’s an unshakable sense that all of them are the naked Tracey. Me, me, me, shouts the art, as it always has done. Tiny bits of man slip in here and there, pleasuring, forcing, fighting, but they’re largely invisible, their presence implied with cursory touches. Their job in her art, you soon notice, is to go missing.

I Never Asked to Fall in Love — You Made Me Feel Like This, from 2018, has a figure in there somewhere, but it’s obliterated by a lake of dripping crimson that would have emptied the blood tanks at Hammer Film Productions. You Kept It Coming, from 2019, is whiter, paler, with a crouching nude searching for somewhere to crawl. Painted on top of a thick crust of white obliterations — as if 20 previous versions have been Tippexed out — the crawling woman is a snail without a shell.

Ever since she decided to stop being a Brit Brat and to start trying to rival the Old Masters in figure painting, Emin has shown an unwavering determination to get it right. It’s been a 20-year fight. But she’s arrived now at a wild and risky painting style — part abstract expressionism, part body torture in the Egon Schiele mode — that demands huge amounts of pictorial courage. Every brave painting is a whisker away from failure.

Munch, meanwhile, fights a quieter fight with loneliness and anxiety. His anorexic women seem always to be comparing their bony reality with the countless Venuses and Cleopatras who preceded them in art; and shivering at the contrast.

Every nude in the anorexic harem is weighed down by a sense of failure. It’s an empathetic art that speaks touchingly of a universal unhappiness. And although it cannot compete with Emin’s insider knowledge when it comes to the inner lives of women, it strikes me as just about the best a bloke can do.

At Tate Britain a brilliant retrospective by Lynette Yiadom-Boakye looks back at 20 years of determination to force her way into the British portrait tradition. While all around her were taking photos and making videos, Yiadom-Boakye was building a portfolio of painted likenesses — oil on canvas! — that can now be recognised as important and revolutionary.

As a black artist she has no obvious precedents in her territory. The artists she responds to and occasionally quotes from are white and male — Sargent, Sickert, Degas — whom she seems deliberately to be taking on with subjects that are unswervingly black.

Most often she paints young men: relaxing, smoking, thinking, listening to music. They feel immediately unusual because the black men of this age we are most used to — the ones who appear most frequently in our media — are footballers, pop stars, protesters or criminals. In this radical rethink, however, they form a beautiful cast of dreamers and poets, philosophers and diviners, sensitive souls and romantic presences.

It’s startlingly effective: a trainload of cultural prejudice is hitting the buffers. Also important are the technical battles that are being waged. Painting dark skin takes you into different pictorial territories from painting white skin. It’s something Yiadom-Boakye draws deliberate attention to by recurrently making her settings as subfusc as possible.

Into these testing darknesses she places her beautiful chaps before setting off on exciting explorations of colour and tone. What a wonderful show.

Tracey Emin and Edvard Munch, Royal Academy, London W1, until Feb 28; Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Tate Britain, London SW1, until May 9