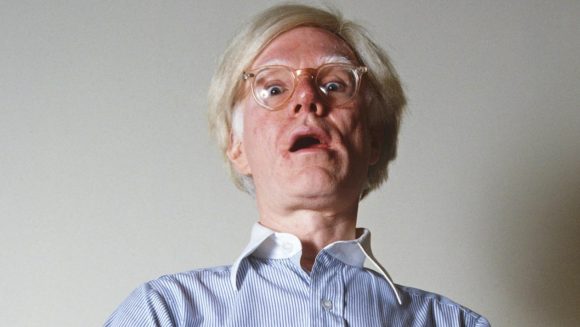

Andy Warhol had a big dick. I reveal this immediately for three reasons. First, to sound an appropriate note for Blake Gopnik’s 976-page whopper of a biography, a tome so intimately informed that it is impossible to imagine its depth of detail ever being out-mined. Second, because the artist’s sex life is a key focus of the book. Third, and most important, because it’s a question that nobody is asking, but everyone is thinking: and if Warhol taught us anything in his art it is not to search too loftily in humanity for motivations and directions.

While we’re at it he also suffered from anal warts, had poor hygiene and succumbed to assorted venereal diseases. So much for the angelic Andy.

The fashion for giant art biographies that inch their way through a big career can be traced back to John Richardson’s mighty reflections on Picasso, the multivolume epic, begun in 1991, that he never managed to complete. Hilary Spurling’s award-clustered Matisse continued the tradition and was followed by Alex Danchev’s formidable Cézanne. These “slow biographies”, packed with forensic detail, transformed presences that were instant and visual into ones that occupied a much heftier cultural space. As someone says of Warhol in Gopnik’s book, he’s “like a feather floating through — a feather that really weighed 5,000 tons”.

But there’s an important difference between this effort and its predecessors. Whereas Picasso, Matisse and Cézanne had reputations whose importance was fixed, Warhol died recently enough — in 1987 — to remain a shifting shadow. Gopnik, a former art critic of The Washington Post and nowadays a New Yorker, clearly has no doubts about the size and scope of Andy’s achievement — the word “genius” gets several tremulous outings — but the view from Manhattan is not yet the view from everywhere else. Warhol’s eventual importance is far from settled.

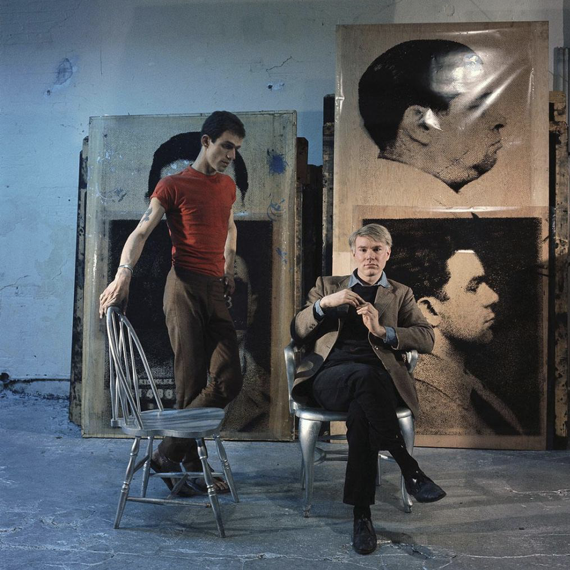

Which is not to say that Warhol: A Life as Art lacks direction or determination. Far from it. The book progresses in tiny steps, year by year, stopping to investigate every notable artwork, and plenty of un-notable ones as well, and it is impossible to imagine anyone finding out much more about Andy than is recorded here. In that sense it’s definitive.

Born in Pittsburgh in 1928, Warhol was actually a Rusyn, a precise Carpathian nationality that spoke its own language, wrote in the Cyrillic alphabet, and, like all Slav minorities, clung together fiercely when it reached America. The poverty of his early years was dark and true. Gopnik devotes some of the book’s best passages to describing its specific flavours.

It was Warhol’s mother, the eccentric Julia Zavacka, who triggered a taste for art. Julia made flowers out of refashioned soup tins, and sold them door to door, thereby forecasting Warhol’s own relationship to soup. In later years, when he moved to Manhattan, she followed him there to look after “her Andy” and never left. Warhol installed her in his basement. The flowery script that was such a distinctive feature of his advertising work in the 1950s was Julia’s script. When he needed more of it, he learnt to forge it.

Before fleeing Pittsburgh, he completed a thorough art education at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, a progressive art school with Bauhaus ambitions. Carnegie Tech brought him bang up to date with developments in modern art, a truth he sought to hide by claiming later that he was entirely self-taught, a natural genius.

Warhol’s past has always felt foggy. Partly because it was mysteriously Central European, but also because he lied about it so regularly. Embarrassed by his lowly origins, he tinkered with his own history. Thus Andrej Warhola called himself “André” in the French style when he wanted to impress his advertising clients, and “von Warhol” when he briefly developed aristocratic pretensions. He lied about his age, too, often chopping off years when he felt the need to appear younger.

Some of this rewriting of his identity was merely a style thing, but there’s a sense as well of a flight from the truth that was emotionally dark. Hugely detailed though he is, Gopnik sometimes feels as if his understandings are too technocratic. The most far-reaching corrective he attempts is devoted to Warhol’s sex life. Earlier observers have told us that Andy was largely asexual. Gay, yes, but tidily and discreetly so. Gopnik bashes that one into the bleachers.

From his first gropes in a department store in Pittsburgh to his daisy chain of younger boyfriends, Warhol was a determined sexual adventurer. Most of the men he seduced can be described as workplace conquests. Most were substantially younger. All confirm a sad progress in the relationship from curt initial sex to a dull love life in which the action stops. Andy took lots of drugs as well, amphetamines and quaaludes, and was also, on occasions, a big drinker. Because his touch was so light, he was really good at blow jobs.

All this is important not only for gossipy Warholian reasons but as an aesthetic rerouting. A gay man, with a fierce gay agenda, Warhol’s sexuality was powerfully impactful. It influenced his choice of styles and opportunities and made him a modernist. As Gopnik astutely points out, Warhol observed America from an outsider’s position. The America that he made the subject of his art, the America of Marilyns and Elvises, of Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo boxes, was the Walmart America of the everyday immigrant.

But big-picture conclusions are not what this book does best. Its diary format, its division into years, is great for detail, but less great for overviews. When it comes to Warhol’s films, each of which gets a slab of book to itself, we are definitely in the realm of too much information. Having sat through the entire eight hours of Empire(1964) — a single shot of the Empire State Building — I cannot share Gopnik’s detailed Manhattan enthusiasm for Warhol’s films. Everything that any Warhol junkie should ever wish to investigate is here: the operation that saved him when he was shot by Valerie Solanas; how he came to paint his Marilyns and Elvises; how Edie Sedgwick came into his life. Every member of the infamous Factory citizenry gets a detailed mini-biography to themselves. You probably need to be a New Yorker to fully enjoy this relentless name-dropping. I found it wearisome.

For all its weight and length, Warhol: A Life as Art feels a tad premature. The next Warhol biographer hasn’t a hope of bringing more detail to the task, that’s been done. What they might bring is a truer perspective.

Warhol: A Life As Art by Blake Gopnik

Allen Lane £35 pp976