I had to laugh. A stentorian declaration from the Serpentine Gallery thudded into my inbox this week, announcing that the gallery’s artistic director, Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the man they call Herr Airmiles, the most travelled atom in the art orbit, was going to cut down on his international trips. “I can contribute to popularising methods of exchange that are more tenable for the wellbeing of the planet,” Obrist revealed in his usual catchy English.

It was hilarious for a couple of reasons. First, because the notion that an art gallery needs so grandly to announce a change in the travel plans of its director points to a serious subsidence of reality at that gallery. Second, because I’ll believe it when I see it. Obrist is such a notorious travel junkie — if Timbuktu had a biennale, he’d be there — that he must single-handedly have melted a couple of inches off the Greenland glaciers in his career with his relentless darting about the globe.

The background to this is the sudden determination by the art world to confront the issues of climate change. A crop of shows on the subject has been promised, notably by the Serpentine, but also by the Hayward Gallery, which is devoting its big spring exhibition to trees. Again, I had to laugh. Only the gods of electricity know exactly how many Amazon basins are needed to keep the Hayward Gallery lit and buzzing with the immersive installations and looming video rooms it favours. Let’s hope it’s less than Tate Modern, which must burn a couple of rainforests a week just to keep the lifts running. The Turner prize, in recent years, has been so devoted to electronic bleeping that its carbon footprint must have been visible from the moon.

For all these reasons, and too many others to list without detouring fatally from this article’s happy destination, we must welcome and even hug Radical Figures, at the Whitechapel Gallery. Devoted to a group of painters who have sought doggedly to remain au courant and pointy without draining the national grid of its amperage, this healthy-feeling event reminds us that art at its best is art at its most basic. Use your eyes. Use your hands. See stuff with the first. Rework it with the second.

It’s been clear for some time that painting was heading for one of its inevitable returns. It’s been especially noticeable among black artists such as Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Njideka Akunyili Crosby, and their artistic grandpa, Kerry James Marshall, for whom the airing of crucial issues of identity and racial memory is too urgent to be delegated to labour-saving devices.

Painting has a self-sufficiency to it, a sense of good husbandry, that suits art’s current mood. And this show has smartly placed a finger on that pulse with a selection of 10 artists who are doing something that people regularly forget painting will always do: renew itself and start again.

From the moment you step in, there’s a sense of uplift. The first artist you encounter, Cecily Brown, is hardly a new name. She’s been prominent for three decades. But Brown’s USP, that she paints while those around her do not, has made her a solitary figure. Here, though, she’s been given a pictorial cartel and cast as an agenda-setter, a task she fulfils spectacularly well with a suite of four gorgeous paintings.

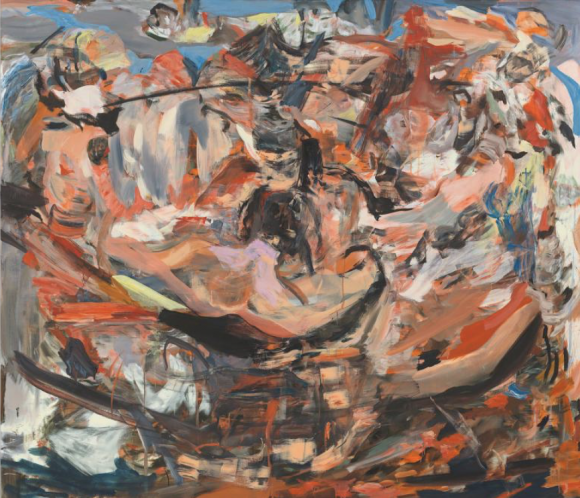

The first one you see, Oinops — a title borrowed from Homer’s Odyssey, where it describes a red and choppy sea — is a pigment thunderstorm from 2016-17. As always with Brown, the first impression of abstraction is complicated by a second impression of flickering figures. You think you see things — a boat, a gale, a shipwreck. But it’s the way the paint skims and dives, leaps in and out of focus like a pod of happy dolphins, that supplies the thrills. When it comes to implying movement while remaining rock-still, nothing lays a finger on oil paint.

Brown’s sense of unbelted enthusiasm turns out to be exhibition-wide. If shows made noises, this one would be whistling. But while she is not adding much that is fiercely new to the abstract expressionist cookbook, especially to the chapters written by de Kooning, other exhibitors here have struck out in radical directions.

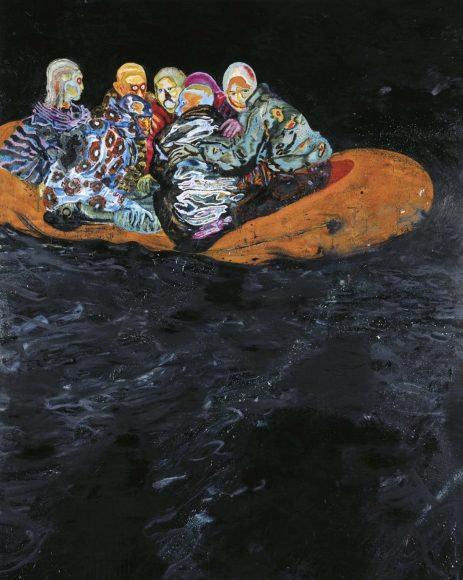

I really like the German painter Daniel Richter and his wacky surprises. In Richter’s case, the four pictures come from different stages of his career, and they add up to a telling precis. The earliest work, from 2001, shows a boatload of refugees bobbing perilously across a black sea. So it’s literal and accusatory. But by his fourth instalment, a picture from 2015 called Asger, Bill und Mark, there is nothing on view that’s easy to recognise. I presume Asger, Bill and Mark are in there somewhere, but their legible outlines have been sacrificed in a fabulously inventive display of mark-making that seems to oscillate between serious and comic. If you told me it’s a murder scene, I’d believe you. If you told me they’re playing poker, I’d believe you.

Tala Madani, born in Iran in 1981, but now working in America, is another oscillator. Her early work pokes fun at a masculine world in which gangs of middle-aged men run around being comically useless in the manner of the Keystone Cops. But these echoes of her Islamic past have grown fainter and fainter, and these days her work is more interested in noticing our universal absurdity. Technically she’s become madly inventive, another key development underlined recurrently here. It may be a painting show, but it’s not painting as we know it.

The shifting identity issues that keep resurfacing, the lack of faith in the old realities, has clearly encouraged an energetic review of the rules of painting. The old ones have been ditched. A bunch of new ones have been invented.

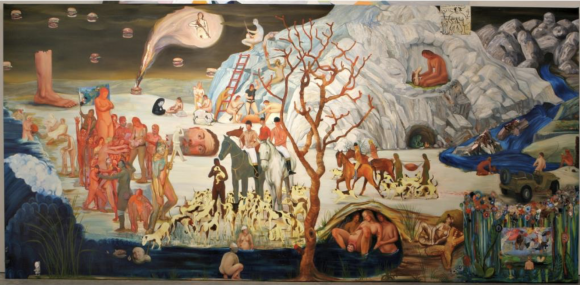

The Kenyan artist Michael Armitage paints on lubugo bark cloth, a local material usually used to wrap bodies for burial. It’s lumpy. It’s got holes in it. If you’ll pardon the paradox, it looks lived in. Richter’s four paintings could easily be the work of four separate artists. Ryan Mosley, who works on linen, aluminium and board, has found a way to squeeze five human heads onto a single neck without the results feeling surreal.

Annoyingly, the show is brilliant on the first floor, but weaker on the second, where it gets taken over by what used to be called Bad Painting. Dana Schutz, Tschabalala Self and Christina Quarles are all repeaters of cartoonish figures for whom painting seems merely another shortcut to the image. There’s little of the visceral enjoyment of the stuff of paint that makes downstairs a joy.

But hey, this remains a fascinating and welcome event that has put its finger on a significant pulse. Over at the Serpentine, Hans-Ulrich Obrist should resist the temptation to fly to Mongolia for the Ulan Bator Biennale and cycle to the Whitechapel instead. This is where the action is.

Radical Figures, Whitechapel Gallery, London E1, until May 10