It is always interesting to see how art galleries describe James Turrell: what they call him in their press releases. He’s so difficult to define, so tough to encapsulate, that the people tasked with coming up with designations for him certainly have their work cut out.

So the Pace Gallery gets 6 out of 10 from me for bringing us “light and space master James Turrell”. It doesn’t trip off the tongue. And there’s a note of Star Wars in it that takes us too far into the galaxies. But for all that, it’s reasonably accurate. Light and space are the things he deals with. And if you are going to call anyone in contemporary art a master, then Obi-Wan Turrell is your guy.

For a start, he’s 76, the kind of age at which you expect to find deeper reservoirs of wisdom in your artists. It is also true that in his hefty American career he has remained notably resolute in his direction: Turrell doesn’t wind, he doesn’t detour. The fact that his art has such a powerful scientific bent to it, and involves such a conspicuous knowledge of optics and physics, gives him a pansophic air. Also, he looks exactly like Michelangelo’s bearded God on the Sistine Ceiling. So I’ve changed my mind about the marks. Let’s hoick it up to 8 out of 10.

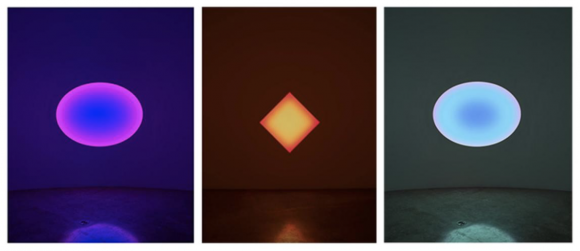

Turrell’s new show at Pace is a sparse installation of just four works. Three form a sequence in the main gallery, while the fourth sits in a room at the back, where it is deliberately visible through a gallery window. You can see it from the street. If you’re a passing shopper, I recommend putting down your bags and watching. Things will happen. Not immediately. Turrell doesn’t do speed. But gently and subtly.

From what I understand of “mindfulness”, it involves a careful and sensuous savouring of the moment: a giving up of yourself to the experience you are in. That is exactly what you need to do with Turrell. And if you do it properly, you’ll be there for a couple of hours, gawping through the window, because that is how long it takes Whitehall, as the work is called, to complete its extra-slow pulsations. Better still, brave the portentous columniation that surrounds the Pace Gallery — it’s in the old Museum of Mankind building at the back of the Royal Academy — and pop inside for some face-to-face transport.

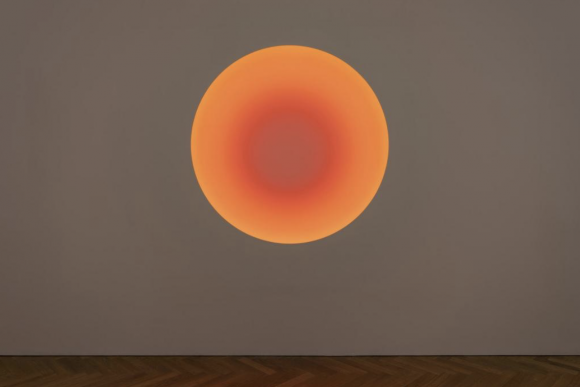

The three works that form an installation in the gallery are named after constellations: Sagittarius, Cassiopeia and Pegasus. Each of them is basically a roundel of coloured light on a white wall. Sagittarius is a horizontal oval. Cassiopeia is a circle. Pegasus is a vertical spheroid. So the first impression here is of a strict geometry, with a mildly authoritarian tang to it, as if you are being told to pay attention.

I started with Sagittarius, which seemed initially to be an oval of cloudy white: not flat, not solid, but simultaneously see-through and not see-through. As I said: cloudy.

The white began to grow pinkish in the middle. Not pink like the sky in a nice sunset, but pink like an exquisite bit of flesh or an expensive blusher. Nipple pink. Then it went red around the edge. Not a fierce red, like a London bus or a telephone box, but a suffused red, with light in it, as if its production involved the use of poppies.

Back in the middle, I began to see greens. Though I couldn’t be certain. You know how greens are. They can feel like blues. Then the greens went, and the reds got bigger, until they filled the whole oval and tinged the space around them. Then the whites returned: back to the clouds. I looked at my watch. I’d been watching for 20 minutes. Every delicious pulse and fade had been engrossing.

So that’s how Turrell works. It’s all in the eyes. As Goethe famously and plangently put it: “The eye has to thank light for its existence.” How it is done is another enticing mystery. You go up to the nipple-pink oval, stick your face in it, and there’s nothing there. It’s not a flat wall, but neither is it an obvious hole. An oval cloud has somehow been suspended in mid-wall by an artist with the mind of a heavily gonged Cambridge physicist. (Unless that really is him up there on the Sistine Ceiling …)

The same thing happens with the circular Cassiopeia, although in that case it’s all about glowing greens and their relationship to yellow. With the final spheroid, we’re with the reds again, but not with the whites — the full poppy-on-poppy experience. As for the work in the window, it’s blue, and square, oriented like a diamond. It made me think of sapphires and how much I love their particular blueness.

We’re talking, therefore, about a kind of op art, a visual geometry that pleasures the eyes. But it is also a kind of kinetic art, because these things are never still. They blur, they pulse. There’s some minimalism in there, too, because all we see are three strict roundels and a square. And it’s science art, because Professor Turrell is precisely manipulating our vision, toying with our perception, calculating the response of the retina. Finally, and least clearly, we’re talking about transcendence. Which is where the fogs get especially foggy.

Is it merely a trick of the light that there’s something churchy about the experience? That the roundels have something of the rose window about them, that the alcoves feel whispery, like a chapel? Is it an accident that the three constellations are arranged in a big glowing triptych, like a giant altarpiece? Forget Goethe. Let’s go back to the beginning and add the daddy of all scientists to the equation. Genesis. Chapter one. “God said, ‘Let there be light. And there was light.’” Hallelujah.

Back on earth, at the Flowers Gallery, they are celebrating 50 years of existence. In 1970, Angela Flowers, the matriarch of the family, started a gallery in London devoted to modern art, with an opening year that included work by Joseph Beuys, David Hockney, Peter Blake and Richard Hamilton. It was impressive then. It’s been impressive ever since.

When I started art-criticing, the Angela Flowers Gallery was always stimulating and always welcoming. It was never a snobbish establishment. Never felt as if it was trying to flimflam or obfuscate in the falsely superior art-world manner. At the Angela Flowers gallery, things felt real. When Britain decided to send war artists to the Gulf War and to Bosnia, it chose Flowers artists — John Keane and Peter Howson.

The fact that the gallery is still there, 50 years later, is a tribute to its deep and lasting value. They have a show, 50×50, looking back at those 50 years. There’s lots to see.

James Turrell, at Pace, London W1, until March 27; 50×50, Flowers East, London E2, until March 7