Rarely have I tiptoed into an exhibition as nervously as I tiptoed into Masculinities at the Barbican. The show is billed as an investigation of the ways in which masculinity has been “experienced, performed, coded and socially constructed” in photography and film since the 1960s. But that, of course, is just its background. The foreground is what is happening right now in New York in the Harvey Weinstein case. It’s Jimmy Savile and Rolf Harris, Ray Kelvin and Les Moonves. When it comes to readings of masculinity, the real world is currently delivering the storylines. Art is just tagging along.

So it was disarming and even kindly of the female curators of Masculinities to begin their artistic show trial with John Coplans’s famous Self-Portrait (Frieze No 2, Four Panels). Produced in 1994, when he was in his seventies, Coplans’s naked tell-all confronts us with a male body that is saggy, hairy, heavily moobed. When I say confronts, I mean confronts. Pushing his ageing nudity into our picture space like a German naturist pressing himself against a shop window, Coplans forces us to notice every saggy inch of his undressed self.

Not showing his head is a clever touch. This is not self-portraiture as character study. This is self-portraiture as evidence of decay. And because the poses he adopts are reminiscent of the heroic ones favoured by classical statues — naked Apollos, Parthenon warriors — the headless Coplans adds a note of pleasing pathos to the mix. He’s no warrior. He’s no Apollo. He’s a 74-year-old everyman with his kecks off, Coplans of Milo, the headless grandad. Brilliant.

It’s an edgy beginning. And it signals a show that is trying to avoid the obvious paths. The long and wobbly shaggy-dog story that unfolds ahead darts down every detour it reaches, and is all the better for it.

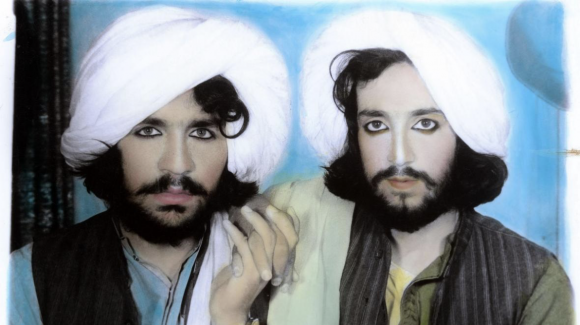

The first corrective proposed here, in a section called Disrupting the Archetype, is that typical blokes are not really typical blokes. Thus, Thomas Dworzak gives us Taliban fighters who put on heavy eye make-up and get themselves photographed in sensuous colour in Afghanistan in 2002. If you had told them they were getting in touch with their feminine side, they would have shot you. But that is what is happening.

The Dutch artist Bas Jan Ader sobs uncontrollably into the camera, because big boys do cry. The Norwegian Knut Asdam presents a close-up of a cocky cowboy urinating into his pants like a teenage bedwetter. Rineke Dijkstra shows us blood-splattered Portuguese bullfighters whose faces are too sensitive for their costumes. Robert Mapplethorpe photographs the young Arnold Schwarzenegger, grotesquely muscled from the shoulders down, shy and awkward from the neck up.

These are eloquent examples, sourced from different corners and many epochs. Whoever found them has been looking carefully. The show has been mounted because we are living through the #MeToo moment in our culture, yes, but it doesn’t see that situation in remorselessly tragic black and white. Fifty-five artists, of every gender and every age group, some as famous as Andy Warhol, others as un-famous as Kiluanji Kia Henda, pop up in busy clusters, on a journey packed to the pecs with fantasy, caricature and energetic side-stepping.

Having established that blokes are not really blokes, and that masculinity is a variable condition, the display sets about exploring this variability. Even the section ominously entitled Male Order: Power, Patriarchy and Space turns out to be surprisingly impish. Piotr Uklanski’s huge collection of cinematic Nazis — played by every famous beefcake from Marlon Brando to Roger Moore — is certainly concerned with images of masculine power, but it also pokes fun at the taste for Hollywood Nazis and highlights the relentless absurdity of their characterisation.

Not that there’s a shortage here of genuine examples of toxic masculinity. The creepiest exhibit is Andrew Moisey’s probe into American fraternities: their rules and their behaviour. Presented as a portentous annual volume, leather-bound and respectable, Moisey’s ugly picturings of drunken students vomiting into sinks, groping strippers, torturing dogs, parading nakedly with their dongs dinging, is topped off with a list of American presidents and the fraternities they belonged to.

Yet there’s proof that women can be just as creepy as men. Heaven only knows what the Polish photographer Aneta Bartos is trying to say in a sequence of troubling pictures in which she shows herself cavorting in her undies with her bodybuilder dad. Annette Messager’s telephoto close-ups of the crotches of passing strangers are as spookily intrusive as an FBI surveillance operation.

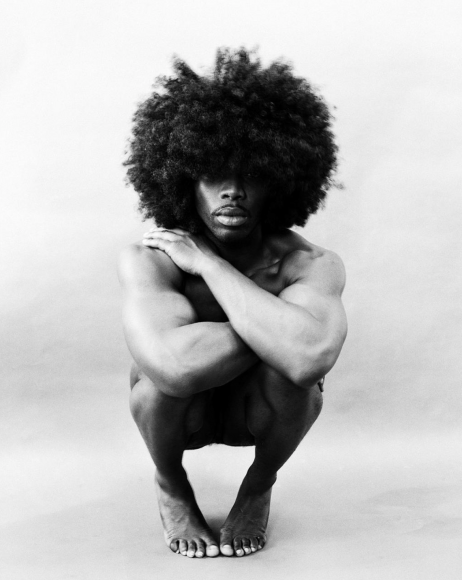

Halfway along, the show’s definition of manliness grows conspicuously flexible. Trans artists pop up to reinforce the core message that masculinity is a spectrum, not a rulebook. A chapter called Queering Masculinity looks at the shortcuts and fantasies involved in reshaping masculinity from a gay perspective. Reclaiming the Black Body remembers how black artists have sought to wrestle back their own identities from the clutches of voyeuristic westerners. In patches, it’s more woke than bloke, but most of it is impressively adult, full of excellently chosen art, more humour than I was expecting, and a heap more wisdom.

At Tate Modern, the rise and rise of Steve McQueen continues apace. He really has been ridiculously successful. On the art side, he won the Turner prize in 1999 and represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 2009. On the film side, he’s made four successful movies, has just been knighted, and in 2014 won the Oscar for best picture with 12 Years a Slave. Alfred Hitchcock and Stanley Kubrick never won best picture; neither has Quentin Tarantino.

What’s interesting about this two-pronged success is how separate it remains. The selection of newish artwork that has arrived at Tate Modern is so determinedly hardcore, it almost constitutes a test of loyalty. Movie fans, stay out. Art fans, come in.

The opening sight is a shaky movie of the Statue of Liberty, shot from a circling helicopter that goes round and round the monument, noticing how grubby it is. There’s a pleasing payoff when the helicopter gets so close that you can see seagulls nesting in the armpits of the great symbol of American liberty. But the camerawork is so wobbly that McQueen may as well have strapped a Bolex to a circling pigeon.

This reliance on basic methods — handheld cameras, haphazard lighting, poky situations — is exhibition-wide and not always successful. The ambition is clearly to keep things extra-truthful, but sometimes it just made them hard to see.

Others have praised Western Deep, the 2002 film in which McQueen journeyed three and a half kilometres into the earth, down South Africa’s deepest gold mine. But by filming the experience on wonky Super 8 film that has no hope of responding to the subtle degrees of blackness down there, he emerges with a grainy approximation that goes from blobby black to blobby black with barely a moment of focus. It’s like entering a scooter in a Grand Prix. If ever a film needed to be sent to Specsavers, it’s this one.

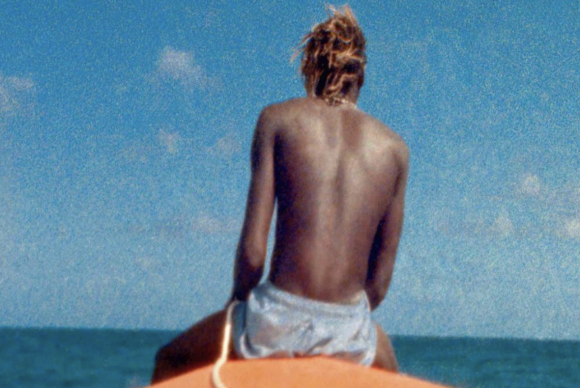

So that doesn’t work. But other bits of the show do. Charlotte (2004) is an edgy close-up of Charlotte Rampling’s eye, which the artist manipulates with his finger before eventually touching her eyeball with a prod that feels thoroughly transgressive. Girls, Tricky (2001) is a sweaty recording of the trip-hop pioneer Tricky singing himself into a trance as he screams out fierce accusations about absent fathers. Best of all, Ashes is a two-screen projection telling the story of a beautiful Grenadian boy who gets murdered in a drugs mix-up. One screen shows him in 2002, on a boat, free and happy. The other screen shows two recent Yoricks digging his grave.

So it’s a deliberate piece of cinematic storytelling, and the only occasion here when Steve Jekyll barges onto the territory of Steve Hyde.

Masculinities, Barbican, London EC1, until May 17; Steve McQueen, Tate Modern, London SE1, until May 11