Dora Maar was not Dora Maar. She was Henriette Theodora Markovitch, born in Paris in 1907 of a Croatian father and a French mother. Gradually she changed herself. First she dropped the Henriette, insisting her family call her Dora. Then, in her early twenties, she settled on the snappy Maar rather than the lengthy and foreign Markovitch. Thus she became Dora Maar, a name that comes out as a vowelly “drama”, if you say it quickly.

It was John Richardson, Picasso’s biographer, who pointed this out to me with a characteristic guffaw when we were making Picasso: Magic, Sex & Death, a big film biography of the master inspired by something Maar had noticed. “Every time Picasso changed his women,” she observed, “he changed his style.” She knew this, of course, because she was one of those women, the original Weeping Woman, Picasso’s mistress in the 1930s and the early war years.

I mention it here because the simultaneously intriguing and frustrating Dora Maar exhibition that has arrived at Tate Modern left me feeling that her insights into Picasso may just as well have applied to her. Not because the show dwells on her lovers — it conspicuously doesn’t: the P-word isn’t even mentioned until near the end — but because there is a striking lack of continuity and fixity about her progress. Not only does she jump from style to style as her life unfolds, she flits, as well, from method to method. This could be six careers lined up in a row, rather than one career advancing.

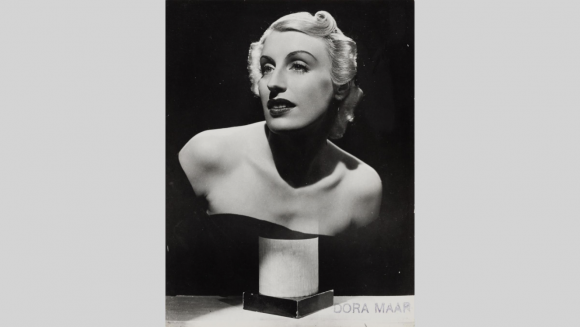

The opening sight, a wall of portraits of her at various ages, taken by various photographers, is the first evidence of this jumpiness. She’s young. She’s old. She’s big. She’s small. A glamorous Maar draws on an art deco cigarette. An old lady in a photo booth stares starkly at us as if she has just been arrested. A potpourri of identities is served up as an amuse-bouche.

Although Maar began her artistic career as a painter — she studied briefly under André Lhote, the excellent cubist — there is no evidence here of these original impulses. How did she start? Who was she? With identity issues dominating the show’s structure, it too often ignores the bread and butter of dates and people.

Instead, we plunge immediately into her career as a commercial photographer. In 1931, having been advised to drop the paintbrush and take up the camera, she adopted the professional name of Dora Maar and started a photography studio with a shadowy figure called Pierre Kéfer. What followed was the most glamorous and obviously successful phase of her career. Working for big fashion houses — Chanel, Schiaparelli — she began churning out exquisite art deco fashion plates characterised by dramatic silhouettes and mysterious props. Perfect bodies cast perfect shadows. Beautiful faces stare beautifully into space.

She also worked for the erotic press, for a magazine called Seduction, for which she produced a harem of stunning nudes. A Ukrainian model called Assia, who gets a section of the show to herself, is so elegantly art deco in her angles and proportions, she looks as if she has jumped straight off the bonnet of a Rolls-Royce.

The show devotes one of its best rooms to this impressive commercial photography, with its mildly sinister 1930s fascination with the perfect human body. All the work here is signed Kéfer-Dora Maar, yet we find out nothing about Pierre Kéfer. Clearly their relationship had something of the Lennon and McCartney about it, so who did what? As a former designer of film sets, was Kéfer responsible for the brilliant lighting? It would have been good to know.

Having impressed with the precision and elegance of her “worldly period”, Maar veers off at a very different tangent in the “socialist” phase that follows. Leaving behind Kéfer and his dramatic studio lighting, she follows her friend Brassaï onto the mean streets of 1930s Europe, with a series of expeditions to Barcelona, London and the suburbs of Paris, where she photographs the poor, the messy, the blighted.

Again, it’s impressive stuff. Ragamuffins in Barcelona, strewn across the streets like litter. Crumbling shantytowns in Paris that could be the favelas of Rio today. The London poor begging in front of banks. Suddenly we’re with a different artist in a different world.

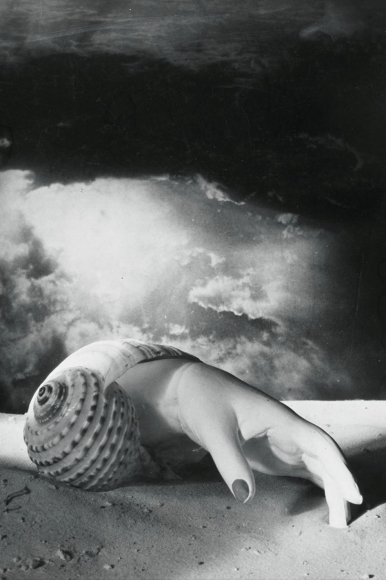

And then, just as suddenly, we’re out of there, too, and in the presence of a fully formed surrealist. A hand emerging from a shell scuttles along a beach like a crab. A sticky blob, with talons for hands, introduces himself as Père Ubu, though he’s actually the foetus of an armadillo.

The surrealist Dora Maar is the Maar we’ve been expecting. Since her death in 1997, her reputation as a surrealist photographer has enlarged noisily, as indeed have her prices. The social circles she moved in — Paul Eluard, André Breton — were surrealist circles, and even in her socialist street photography she seemed as interested in unexpected juxtapositions as in the plight of the unfortunate.

But, effective and hilarious though she was as a surrealist — in an image called The Pisser, a young boy relieves himself so copiously in a posh Parisian house that he has turned the entire floor of the salon into a marsh — there’s a sense as well of these aesthetics having been learnt rather than invented. It’s an impression magnified in the show’s next phase, when, finally, Picasso enters the story. She met him in 1935. Picasso himself remembers seeing her for the first time at the cafe Les Deux Magots, where she was playing that game with a penknife where you stab yourself between the fingers, moving faster and faster. She kept missing, and her fingers were soon covered in blood. Quite an entrance.

He was impressed, too, by her intelligence, and by the firm contrast she offered to his mistress at the time, the blonde and submissive Marie-Thérèse Walter. It’s a comparison made obvious by the abrupt appearance in the show of Maar the painter. Encouraged by Picasso to pick up a brush again, one of her first efforts in the new medium is a portrait of him that is so Picasso-like in style — a profile that’s also full-face: one eye where the cheek should be — it might almost be a parody.

Much more convincing is a double portrait called The Conversation, in which she shows herself sitting at a table with Marie-Thérèse. Dora has her back to us, Marie-Thérèse faces the front. Dora is dark, her rival is blonde. So it’s an image that feels as if it is demanding a choice from you-know-who, by far the most interesting of her Picasso-era paintings precisely because it’s the least Picasso-like.

Maar pops up in many guises in these Picasso years: it’s the exhibition’s most fertile stretch. She’s the copycat painter. She’s the inspiration for Weeping Woman, seen here in a couple of versions. As a photographer, she records the genesis of Guernica, stage by stage. There’s even a marvellous little interview with her about these events, conducted in 1990 by Tate Modern’s current director, Frances Morris.

What’s missing is a sense of trauma. If you’ve read the memoirs of Françoise Gilot, the mistress who usurped her in Picasso’s life, you will know what a severe breakdown Dora suffered when Françoise took her place, and how fierce and scary were the religious beliefs that underpinned that breakdown. Gilot tells the story of Picasso and Eluard going round to visit Maar and of her shouting at them: “Get down on your knees before me, you ungodly pair.”

I mention her religious manias because their absence from the show feels like a whitewash, and because the collapse of her mental stability offers an explanation, perhaps, for the descent into awfulness that characterises the concluding moments of this bumpy journey. Dear me, her final efforts were bad.

Her last paintings, smudgy daubs with a sense of landscape about them from the 1950s and 1960s, are horrible. The photographic experiments from the 1980s, created by placing her rosary onto sheets of darkroom paper, are just as bad. It’s a sad ending to a career that feels as if it has concluded with a smash, like a vase that has been dropped.

Dora Maar, Tate Modern, London SE1, until March 15