How much do you know about string theory? Before I staggered round the extraordinary Anselm Kiefer exhibition that has arrived at the White Cube gallery with an enormous thump, like a slab of muddy Norfolk dropped from the sky, I knew next to nothing about it. Now, having been prompted by Kiefer to research the topic in depth, I still know next to nothing about it. These are mysteries of deeper physics that no ordinary mind can grasp. Here, though, is what I think I have learnt.

String theory is a mathematical model that seeks to understand the forces holding the universe together, not as a collection of particles, but as a net of strings. These strings connect everything to everything and underpin every force. So it’s a theory of everything, a successor to Einstein’s theory of relativity that attempts to explain the fundamental make-up of the universe by visualising it as a giant cauldron of spaghetti, rather than an enormous box of marbles.

Back off, Cambridge dons. I know I sound like a donkey trying to pass the entrance exams for Trinity. But art doesn’t work the way science does. Besides, I suspect that Kiefer, who puts an astonishing amount of effort into visualising and understanding string theory at this outrageously ambitious event, hasn’t really grasped it more fully than I have. What attracts him is a crude truth: everything is connected to everything.

Titled, portentously, Superstrings, Runes, the Norns, Gordian Knot, this rousing event begins with a giant installation that runs down the middle of the gallery like a spine. Consisting of no fewer than 30 gloomy vitrines, each more than 12ft high, the colossal corridor of doom gets straight down to the challenge of conveying the heft and import of string theory to visiting numbskulls, while at the same time squashing our hopes.

Every vitrine is filled with a messy tangle of electrical cables, with ambitions to evoke the convoluted strings of the universe. Scrawled across the glass are daunting equations, borrowed, I assume, from genuine calculations. And inserted brutally among the cables is an assortment of battered farm implements, a scythe, an axe, seeking, I imagine, to connect the scientific mess of the present with the nostalgic textures of a rural past.

So it’s all a bit laborious. The entangled electrical cables feel too literal. And once you’ve seen five of the 30 vitrines, you’ve seen them all. Where it does work is in preparing us for the tone and subject matter of the gigantic paintings that lie ahead. If you’ve got a bad neck, be careful. There’s a lot of looking up to be done.

From the start of his career, back in Germany in the 1970s, Kiefer has weaponised the size of his art. His paintings make us feel tiny. Envelop us. Trigger our sense of awe. When I quipped at the top that the show felt like a slab of Norfolk that has landed on the gallery, I was searching merely for accuracy. Most of the art here seems to have been created by a tractor that has crisscrossed a muddy field: the heavily furrowed slabs of land have then been tipped on their side and pushed against the wall.

Elsewhere, monstrous visions of the cosmos at night tower over us like expanses of wartime sky, filled with violent explosions and flickering stars. It’s rousing stuff. Unfeasibly large. Outrageously ambitious. And genuinely exciting. Kiefer may have been around a long time, but I doubt he has often overwhelmed us with size as effectively as he does in this volcanic eruption of paint, sticks, furrows and ashes.

Buried somewhere in the mud — in scratched-out furrows and hovering meshes — are the facts and issues of string theory. Their point, I imagine, is to make evident how the physics of the universe connects us across time as well as space; across all our histories and all our myths. In the biggest of the painted skies, the names of the 12 tribes of Israel make a sudden appearance, like a fateful new constellation discovered in the heavens. Above a particularly scarred, muddy landscape, the Seven Seals prophesied to John in the Revelation are counted down apocalyptically on the horizon.

A room full of paintings devoted to the Gordian knot is especially successful at evoking the sense of a blighted history. In the original story, Alexander the Great, confronted by the intractable problem of the Gordian knot, solved it by slicing the knot in half with his sword. Here, the brutal severing of the strings that connect the universe seems to have ushered in a permanent winter. The snow-filled land, scribbled over by straggly branches, is stuck in unshiftable twilight. The axes attached to the centre of every picture — real axes, battered and ancient — have inflicted a damage that’s irreversible.

All these fuzzy hints and clues, the mythical interconnections and elusive names, keep leading back to the same destination: to wartime Germany and everything that was lost there. These days, Kiefer lives in France, far away from his native Black Forest, but, as we all know, because he keeps proving it, you can take a naysayer out of Germany, but you can’t take Germany out of a naysayer. National history sticks to his art like clods of earth picked up on a muddy walk.

The Nordic runes mentioned in the title are here because their spiky shapes rhyme so naturally with the broken branches and dead tree stumps that stud the burnt-out land. The furrows in the fields running relentlessly towards the horizon are instantly reminiscent of the crosses in a war cemetery. The constant use of landscape as a metaphor for the despoiled state of the earth is in itself a trope of German Romantic painting.

The result of all this doominess is a particularly impressive Kiefer showing. Big subjects drawn from the worlds of religion, mythology and science are coloured, effectively and excitingly, with the terrible blackness of German history. As always with him, the Second World War doesn’t actually seem to be over. The fields are still burning. The bombs are still dropping. Wagner is still playing. And the tanks are still ploughing through the mud.

But to see all this as just glum reminiscence would be a mistake. Remember string theory. The whole point of this show is to connect the past with the present. In one of the final pictures, the blackened furrows in a scorched landscape lead your eye to a building that feels immediately familiar. It took me a moment to recognise it. But then I had my Mark Francois moment. Bingo. It’s the European parliament.

At the Stephen Friedman Gallery, Ged Quinn, who used to be in the Teardrop Explodes, but has since turned into a reliably interesting painter, has also had a Teutonic epiphany. In his new show, Quinn, too, is busily referencing the German landscape tradition. But where Kiefer sees desolation and loss, Quinn sees hope, poetry and fairy-tale atmospheres that belong in a story by the Brothers Grimm.

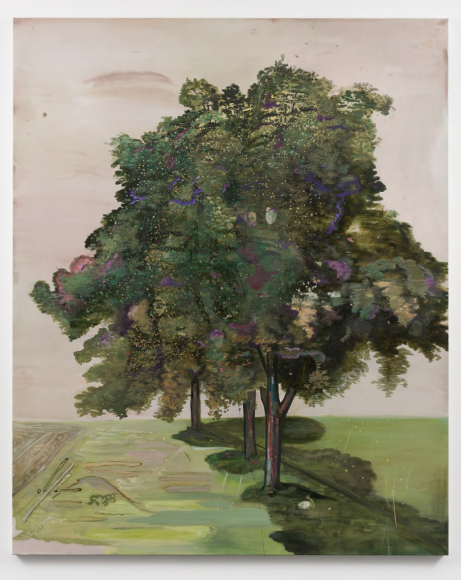

The resulting paintings make you want to go “Aaah” a lot. A linden tree, standing tall in a pink landscape, is surrounded by specks of light that glow like fireflies: it’s actually linden pollen, cascading magically from the branches. In the middle of a pine forest, a beautiful lake of lapis lazuli blue beckons to us, so enchantingly.

It’s a sweet vision. But too innocent for me. When it comes to Germanic truths, Kiefer and Wagner seem infinitely more trustworthy than Ged Quinn and the Brothers Grimm.

Anselm Kiefer, White Cube, London SE1, until January 26; Ged Quinn, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London W1, until January 18