Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits, at the Royal Academy, would certainly have set out to impress and interest us. But although the show achieves its second ambition — how can it not have, given what a strange and fixated cove he was? — it wobbles on the first. Because the unexpected truth revealed here is that making art was a career-long struggle for Freud. He had plenty of black magic in his head, but not much in his fingers. And these failings are made extra evident by the recurrent and unsettling evidence of his self-portraiture.

It’s unsettling because his fascination with his own presence had a neurotic edge to it. Were he around today, he would dispute any and all touchy-feely readings of this self-absorption, because he was the type who disputed everything. But the impression here is of an actor so obsessed with his role that he cannot tear himself away from the bathroom mirror.

Some of that feeling will be due to the unusual make-up of this show. Its curator is David Dawson, Freud’s longtime man Friday and reliable model. As the keeper of the records, he has an address book to kill for and enough personal clout to fill this event with unfamiliar materials from distant corners of Freud’s oeuvre. Armed with the knowledge that self-portraiture was a more insistent focus of his master’s attention than many of us have realised, Dawson has been busily scrumping in private collections and has returned to the academy with an armful of surprises.

The show begins in 1940, when Freud was 18 and should already have been capable of producing something more fluent than the blobby, circular full frontal that opens his score here. Blobby Self-Portrait as the Man in the Moon would be my title for it. Even allowing for the fact that some of the clunky primitiveness may have been deliberate, it’s a feeble opening effort. A self-obsessed 18-year-old is painting like a self-obsessed 14-year-old.

What it does have about it is an air of showy authorship. What a ghastly child Freud must have been. Born in Berlin in 1922, the grandson of Sigmund Freud, little Lucian was obviously brought up with lots of intellectual stimulation, but not nearly enough hugs. His father was an architect, his mother a classicist, and between them they managed to make him feel simultaneously special and bitter. “From very early on [my mother] treated me as an only child,” he complains unpleasantly in the catalogue. “I resented her interest.”

The early parts of the show are filled with uptight drawings, scratchily done on scraps of paper, from which an unhappy Freud stares persistently at us through slitty eyes that belong on a caricatured snake in a painting of paradise by, say, Lucas Cranach. Dear me, what a spitty presence. This visual anger would surely have been understood by his grandfather as a response to being cast adrift on foreign shores. Brought to England in 1933 to escape the Nazis, sent to boarding school in Devon and Dorset, Freud had plenty of reason to feel cut off. And this effortful alienation never lets up in the show ahead. Four rooms of paintings. Not a single smile.

Interestingly, the exhibition paperwork tells us his early art was done sitting down, working on his lap on a board, which explains some of its sense of cramp. There’s not a whisper of breadth about early Freud. The laborious precision he attempts instead is the best his stiff fingers can manage. To put it bluntly, he really wasn’t very good at drawing.

When he does attempt something more ambitious, with some clunky symbolic paintings, the results are even less impressive. In Man with a Feather, from 1943, he stands forlornly on a street corner holding a white feather given to him by an early girlfriend, while an absurd crow in the window behind tries to infect the atmosphere with some corvine doom. It’s like watching LS Lowry pretending to be Gauguin.

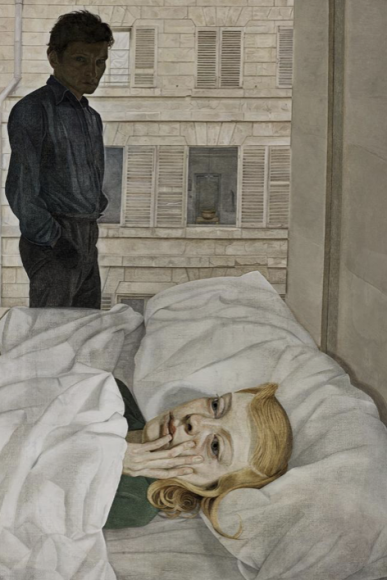

Not until we get to 1954, many women later, does he finally perfect a drawing style that can convey true psychological darkness. Hotel Bedroom shows him in Paris with his second wife, the Guinness heiress Caroline Blackwood. She’s lying in bed, lost in fearful and private thoughts. He’s backlit by the window; a creepy black shadow who should be looking at her, but looks instead at us, Travis Bickle-style. Stylistically, it’s another helping of stiff precision, but the mood is involving and fraught. “Get out of there, Caroline,” you feel like whispering. “He’s behind you.”

Apparently, Hotel Bedroom was the last picture Freud painted on his lap. Encouraged to attempt something broader by his Soho drinking buddies, the double Franks, Bacon and Auerbach, he began working standing up, in front of an easel. He also swapped the fine sable brushes with which he’d been dabbing away rigidly for a decade for the coarser hog’s hair recommended by Bacon. Suddenly he was back to square one.

The following years are another blur of low achievement. Everything gets fragmentary or is left unfinished. In a conspicuous effort to broaden his touch, he takes up watercolours and battles, with little success, for a fluency that taunts him. A selection of cubist heads from the early 1960s see him struggling mightily to discern the essential shapes of his own physiognomy. If you wondered why his infamous portrait of the Queen was quite so bad, here’s the evidence. Achieving a likeness was a big ask for Lucian Freud.

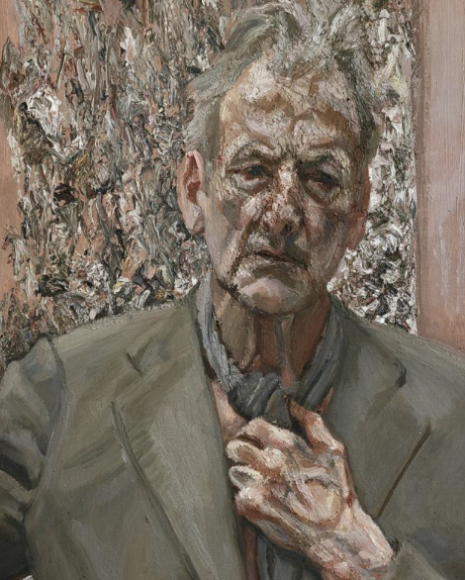

It isn’t until we get to the 1980s that we finally arrive in a space filled with full-blown achievement. The large paintings of friends and family he began to produce have moods that are as neurotic and awkward as any that came before, but their pictorial presence is finally bold, finally confident.

Two Irishmen, one old, one young, share an edgy double portrait. Their physical closeness seems to exaggerate their psychological separation. But see the fuzzy face painted loosely on a small canvas in the background. It’s Freud, adding to the unease by smuggling his problematic presence into the scene.

In the image opposite, his son Freddy stands before us, bone thin and naked, in a picture that demands comparisons with martyrs and Christs. But look who’s reflected in the window, spying on the tension. Insistent shouts of “I’m here” enliven these strange, bold portraits and make them doubly interesting, because Freud’s role in them is to be the cherry, not the cake.

Unfortunately, the show decides for its finale to return to self-portraiture proper and, therefore, to an unhappy atmosphere of effort. In its final image, the painter, aged 70, stands droopily naked with his palette in one hand and his palette knife in the other, an art Spartan — a SpARTan! — holding his weapons aloft.

From a distance, it’s jauntily mock-heroic. But when you get close, big blobs of paint and repaint loom up clumsily, clogging and smudging the face and genitals. He may as well be tarmacking a road.

Lucian Freud: The Self-Portraits, Royal Academy, London W1, until January 26