The trouble with being a celebrated artist is that when you die, your reputation falls into the hands of others and they can do whatever they please with it. It’s happened to all the masters. First they were forgotten; then they were remembered. One age likes your portraits; another likes your landscapes.

When I was a student, the only way of reading William Blake was as a half-mad loner raging against his times, a uniquely fierce presence in British art, noisy, fiery, demented. At night, the Angel Gabriel was said to come down to him and tell him what to paint. He was against slavery. Against the rich. Against mediocrity. His age had one set of values; Blake had another. Or so I was tutored.

Tate Britain, bless it, is begging to differ. The gallery possesses the world’s largest hoard of Blake’s outpourings, and every now and then these are unwrapped and re-presented to us, with shifts in emphasis here and there.

The latest effort — a big career survey entitled, starkly, William Blake — is the Tate’s fourth stab at the subject, and while it doesn’t serve up an entirely fresh artist, it does go out of its way to see him from different angles and to quieten down some of the fury. Where the usual William Blake plays at 150 decibels, this one plays at a mere 140.

Of course, no one is suggesting that Blake (1757-1827) was just an ordinary Georgian, Mr Reasonable, a tranquil product of his times. The route masters here may be wearing new specs, but they’re not blind. One glimpse of the three-headed thingummy with the David Seaman ponytail and the horse-headed trident, rearing up from the gangrene of hell in Blake’s notorious The Number of the Beast Is 666, makes instantly clear that we are not dealing here with normal normality.

What the show does do is to fit him more snugly into his context. Thus the opening room is devoted to his days at the Royal Academy. Later, Blake railed furiously against the academy’s methods and strictures — and especially against its first president, Sir Joshua Reynolds — so it’s easy to forget that he was once a student there, and a dutiful one at that. A selection of drawings from classical plaster casts prove him to have been reasonably adept, but no more. At least he was better than his brother, Robert, who appears also to have studied at the academy, and whose scribblings make obvious that in those days anybody could get in.

Before the academy, Blake was apprenticed for seven years to the master engraver James Basire. So that’s a decade of study, all bankrolled, happily, by his father, a successful stocking seller from Soho. It wasn’t a privileged background, but it was gently paced and moderate. And that’s revision number one.

Revision number two is the looming presence in the story of Blake’s loyal wife, Catherine, who appears next to him on the opening wall, and who seems to have done much of the heavy lifting in the 45 years they were together in life and art. All the way through the show, there are suggestions that Catherine did this and Catherine did that, including colouring some of the most delicate images we see. The caring wife, the helpful father, are soon joined by a gang of generous patrons who keep him in commissions for the rest of his career. For a loner, he sure had a lot of help.

A section entitled Money details how he simultaneously maintained a successful career as a jobbing engraver. Given how unshakably he settled on his mature style in his personal work, it’s something of a relief to see him trying out so many different moods and approaches in his day job. Blake may have protested furiously against poverty, but he never actually experienced it. He was too busy engraving the works of William Hogarth or illustrating comic episodes on the streets of London.

All this restores some balance to his tale and dampens some of the fires. The weird amalgams of poetry and art that constitute his nocturnal work are presented in their original book forms, where they are, in the main, underwhelming. Bring a microscope to view them. The self-made, self-published copy of Songs of Innocence and Experience included here is not much bigger than a fag packet.

Not that the swirling torrents of cascading vocab make more sense when helpfully enlarged in subsequent editions. When it comes to Blake the poet, I am happy to leave him to the literature fiends. Take him away and keep him. He’s all yours. The wondrous thing about art, however, and it’s especially true of Blake’s art, is that it has a life of its own, and no gatekeeper in the world can successfully force it down a path it doesn’t want to take.

Blake knew this, because he soon began publishing his illustrations on their own, without commentary or text or poetry. And suddenly the whole show catches fire. And a figure immediately recognisable as the old William Blake — fiery, demented, brilliant — bursts out from its cage.

His illustrations for Milton’s Paradise Lost are, quite simply, some of the most inventive religious imagery ever produced. Countless artists had already told the story of Adam and Eve. None of them ever imagined it as independently, as weirdly, as strikingly as Blake does.

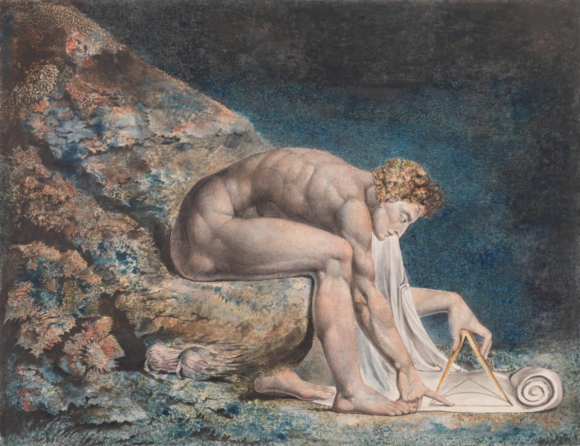

Earlier in the show, his debt to Michelangelo is unmissable, with big bearded men and small neoclassical women acting out clunky dramas with extra-large Sistine gestures. But although this obvious Michelangelo influence diminishes, something that never disappears — indeed, it grows — is a huge Sistine faith in the way art must work, how it must strike you between the eyes like a lightning bolt.

The thunderous frontispiece for America a Prophecy; Nebuchadnezzar crawling on all fours though his dismal cave; The Beast from the Sea gurning apocalyptically at us from seven faces at once — this is art that holds nothing back. Its effect feels closer to getting drunk than to looking at pictures.

Having tiptoed carefully through the opening stretches of this superb show, I found myself swaying through its final rooms. All of Blake’s most notable work is here. Plus plenty of the bad stuff, because he never lost the ability to be dreadful. Not even Piero della Francesca ever painted a baby Christ quite as ugly as the one Blake forces upon us in his Virgin and Child in Egypt, from 1810.

Something else that grows is his frustration at not being able to work on the scale he wanted. The A4 size of so much of his art — and the false sense of repetition it creates — was the result of lack of opportunity, not lack of ambition. In a clever move, the organisers have installed a wall-sized photograph of St James’s, Piccadilly, the Blake family church, then magicked into it an enlargement of one of Blake’s tiny crucifixions, so that it fills the entire altar wall. It’s shockingly impressive.

William Blake, Tate Britain, London SW1, until February 2