Picasso was monstrously superstitious as well as monstrously egotistical, and the two weaknesses had a way of cancelling each other out, so he would certainly not have appreciated how lucky he was to have John Richardson as his biographer or Françoise Gilot as his mistress. Richardson’s telling of Picasso’s story, in the three volumes published so far, is the finest artistic biography ever written, a definition-changing fingertip investigation of a perverse and volcanic life. So good is his tussle with the monster that Gilot’s paving of the way has been unfairly overlooked.

She was Picasso’s mistress in the decade immediately after the war. She bore him two children, and when her decade in the furnace was up she left him, the only mistress to do so. But when My Life with Picasso was finally published in 1964, the Picasso fan club rounded on her and the book was greeted with a tsunami of shock and criticism. How dare she betray the Minotaur. What kind of a woman so flagrantly breaks a trust?

To stop the publication, Picasso launched three legal challenges, all of which failed. In a spiteful riposte, he disinherited Claude and Paloma, the children he shared with Gilot, and the warring parents never saw each other again. Thus a superior literary achievement was drowned out by the scandal that greeted its appearance.

I hope it doesn’t happen again. The decision to republish has been prompted, in a large measure, by the #MeToo movement, as Lisa Alther admits in her introduction to the new paperback edition. So there’s already a context in place that might once again distract from the quality and purpose of Gilot’s memoir. My Life with Picasso is many impressive things, but most certainly it is not a revenge document or a Picasso-kicking or a #MeToo kiss and thrust. Mistaking it for any of those things would be plain wrong. From the first word to the last this is, above all, a love story. Painful, yes. Complex, yes. Doomed, yes. But still a love story.

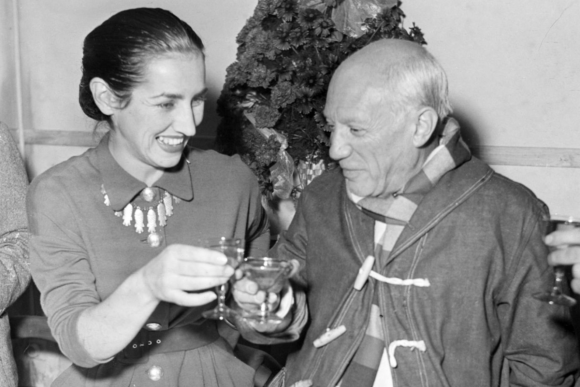

Gilot met Picasso in 1943, when she was 21 and he was 61. He picked her up in a restaurant, coming over to her table with a bowl of cherries. She wanted to be a painter. He was already the most famous in the world. Nothing happened straightaway. His comic attempts to seduce her included taking her up onto the roof of his studio and showing her a giant penis that some workmen had drawn on the house opposite. Did she know what one of those was? Yes, she did. When she finally succumbed to his relentless nagging — Picasso the nagger, going on and on until he got his way, is one of the central characters in her tale — “he was very gentle, and that is the impression that remains with me to this day — his extraordinary gentleness”.

Gilot writes so well about the opening rounds of her Picasso time. She has an ear for a good anecdote and, as everyone who was anyone in global culture turned up at some point on the doorstep, her impressive powers of recall have a field day with the cast list. Brassaï, Malraux, Cocteau all shuffle amusingly in and out of the studio. After the liberation of Paris, Hemingway pops in, but Picasso isn’t there, so he leaves a box of grenades as his calling card. “To Picasso from Hemingway.” A visit to Gertrude Stein turns into a painful confrontation with Alice B Toklas, “dressed for a funeral” and sporting a “furry moustache”, who hisses at her “like the sharpening of a scythe”.

Fun though they are, these pointy anecdotes never get fully in the way of the book’s real purpose, which is to trace and understand her developing relationship with Picasso. At first glance, it’s a classic old man/young girl confrontation, and many will be determined to see it only as that. But Gilot takes great care to inject complexity into the plot line. On her side of the story, it’s clear that the relationship with Picasso is a response to the behaviour of her father, who filled her head with art and literature when she was a little girl, then beat her up when she told him she was going to be a painter. Conquering Picasso, you feel, is a message to her dad.

Picasso’s motives are more practised, but no less complex. He can be a brute, and a remarkably inventive one at that, but for three-quarters of the book he is mainly funny and compelling, a sexagenarian with the instincts of a schoolboy. He falls for her because she is untouched (“If the wings of a butterfly are to keep their sheen, you mustn’t touch them”), but also because he can talk so easily to her about art.

It is here, in the conversations with her antique lover about art, remembered in extraordinary detail, that Gilot’s book mines its second seam of brilliance. They are some of the best conversations about 20th-century art you will ever encounter. I particularly recommend the discussion of cubism, and Picasso’s insouciant explanation of why he only added the recognisable features — a moustache, a guitar, an eye — at the end, as a deliberate enticement for his audience.

So the first three-quarters of the book offer a gripping mix of love, aesthetics and hilarious anecdotes. But then suddenly it darkens. Having persuaded Gilot to have children to fulfil herself as a woman, Picasso turns into the monster we have been expecting from the beginning.

When she entered his life, he was already a serial collector of women and her encounters with his previous conquests make for uncomfortable reading. Picasso’s Russian wife, Olga, stalks her, and deliberately walks across her hands in stilettos when they meet on a beach in the south of France. Poor Dora Maar, usurped by Françoise, has a religious breakdown and demands that Picasso kneels before her and repents.

When he turns 70, Picasso begins a string of seedy affairs designed to cheat time, and she finally sees him for what he is — a cruel and wilful child hiding in an ancient body — and decides to leave.

But it is another of this book’s many strong points that it is only when the illusions pop for her, that they also pop for us.

Clumsy seducer

Picasso’s seduction technique with Gilot was rather hammy. Whenever she came to visit him in his often crowded studio, he would always look “for some excuse to get me off into another room where he could be alone with me for a few minutes”. One time, it was to get her some tubes of paint. On another occasion, it was to help her dry her rain-soaked hair. Another time, he managed to manoeuvre her into his bedroom, picked up a book and asked: “Have you read the Marquis de Sade?”

Life with Picasso by Françoise Gilot and Carlton Lake

NYRB Classics £14.99 pp356