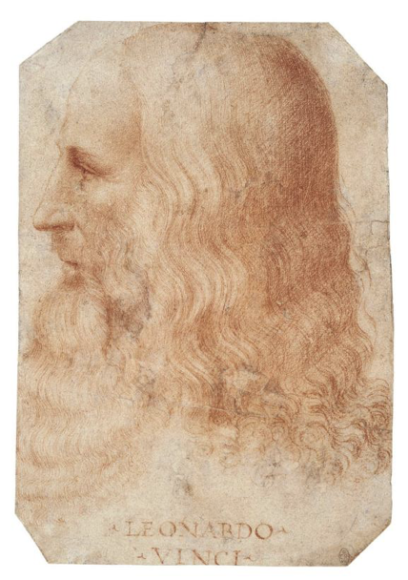

No artist has revealed the stupidity of the modern world as successfully as Leonardo da Vinci. It’s as if the great inventor has successfully invented a mechanism for luring out idiots, fantasists and chancers — himself! And it isn’t one kind of idiot he attracts. Leonardo gets the full house.

There’s the rich idiot with so much money to burn that he throws away $450m for a botched-up portrayal of Christ, some of which may be by Leonardo. There are the Mona Lisa idiots who cannot let a year go by without coming up with yet another preposterous theory about her secret identity. She’s a man. She’s a self-portrait. And all that. Finally, there are the science idiots, determined to proclaim that this or that squiggle by the master is actually a prototype for the hairdryer, or whatever.

What this merry band of idiots have in common — apart from their tragic contemporaneity — is the shortage of material they have to deal with. The poet Paul Valéry once confided: “I write half the poem. The reader writes the other half.” With Leonardo, the ratio is more like 1:99. So little about him is tangible that huge tracts of his achievement can be invaded by marauding numpties.

In these unfortunate circumstances, what can the determined seeker after truth do to assuage their hunger? Where to go, what to see? The Louvre is a waste of time because in between you and the Mona Lisa will be thousands of package tourists clicking their iPhones. Libraries are a waste of time because the many miles of literature they hold on the subject consist mostly of gas. Milan is a waste of time because The Last Supper, in Santa Maria delle Grazie, is chiefly the product of 500 years of crumbling restoration. No. If you want to grab something real, the only place to go is the drawings.

Luckily, on the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s passing, exactly such an opportunity has arrived on our doorstep with the appearance of a superior selection of his drawings at the Queen’s Gallery, in Buckingham Palace. Acquired by Charles II, bound up in a single volume, this treasure trove was originally bequeathed by Leonardo himself to his most loyal pupil, Francesco Melzi. It’s the most complete representation there is of his talent and his journey.

Of the 600 drawings in the Melzi collection, 200 have been selected for this display. And they are the route to the truth about him, because they were so rarely started to be finished. Their purpose is to investigate, to try out. They are a vehicle in which Leonardo’s thoughts could be visualised, an illustrated gym in which his imagination could be exercised. They are particularly important because he was such an instinctive procrastinator. Every Leonardo painting was accompanied by a convoluted campaign of trying things out.

Of all the unfinished paintings that make up such a big hunk of his output, the one I would most have wanted to see completed is the Adoration of the Magi, started in Florence in 1481. It’s his most ambitious surviving composition, 30 figures and as many animals huddled around the still figure of the Virgin Mary like a stormy sea surrounding a rock. The mad crowd scene survives as an unfinished work in the Uffizi, in Florence. It’s impressive. But it can only hint at what could have been had he spent less time starting and more time finishing.

He drew the horses from every angle. There’s an ox. There’s a back leg. There’s a horse being measured for no good reason, except that Leonardo was an instinctive measurer of horses. Helpfully, the Queen’s Gallery curators have included a blow-up of the unfinished Uffizi picture above this crowd of dazzling inkings, so that we can visualise what he was heading towards. But it also makes clear how keenly he headed down the nearest byway.

It’s a story repeated throughout the show. He gets a project. And leaves it hanging. The Last Supper for the refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie. A war scene for the council chamber of the Florentine Republic. An equestrian statue for the Sforzas of Milan. He starts investigating the possibilities, but each possibility leads to another possibility. And then another.

While preparing to paint a nude John the Baptist, he gets interested in anatomy, originally to get the Baptist’s pose right. But the anatomy proves so fascinating that he spends the rest of his life continuing the investigation. So he decides to write a treatise on it. But never finishes it. Or the painting.

While painting Leda and the Swan, he gets interested in the plants around Leda’s feet. So he starts a multi-drawing exploration of all the horticulture he can find. The result is a gorgeous row of flower drawings: sedges and roses, burweed and stars of Bethlehem. Suddenly he’s Monty Don. The sheer randomness of his approach is made beautifully clear by a sudden drawing of the hairstyle at the back of Leda’s head: the side we never see in the picture.

There are two ways of understanding this relentless ability to go off on tangents. You can see it as spectacular proof of his multivalent genius, his insatiable curiosity, which is what we tend to do these days, as we drift further and further away from his reality. Or you can see it as an addiction to fiddling. A chronic inability to complete what he commences.

Certainly, the idiocy he encourages in modern audiences is prompted chiefly by an absence of concrete information and a shortage of completions. And that cannot be a good thing. Drawings are the perfect vehicle for him because they encourage exactly this kind of shooting from the artistic hip.

The present show is filled to the rafters with intriguing detours, dazzling titbits and busy crammings of complex details. His touch is so flighty and quick that you feel his breath on your cheek as you lean in for a better look at the acorns or the horse muscles or the drawing of the foetus in the womb or the beautiful Milanese profile of a girl or the endless studies for the apostles in The Last Supper.

But something else you get from this intoxicating parade is various bits of bad news about him. The lack of determination that characterised his completion rate made him an eager accomplice of whoever paid for his time. And he wasn’t choosy.

When the French invaded Milan, he went happily to work for them, preparing yet more unfinished equestrian monuments to their glory. That is how he ended up in France for the big death we are commemorating this year: a mercenary with his hand out. For the Sforzas in Milan, he devoted most of his creative energies to inventing horrible war machines that could most efficiently murder as many as possible. The row of caricatures that constitute one of the highlights of a show filled with highlights are, finally, rather spiteful and mean. He mocks an old man for falling for an old woman and disfigures them both in his portrayal. Among the greedy gullibles being robbed by grimacing gypsies in a comic street scene he imagines is an unpleasantly caricatured Jewish face that would these days get him thrown out of the Labour Party. Or not.

Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing, Queen’s Gallery, London SW1, until October 13