When you’re an adult, it’s easy to forget that the world is full of wonders. Too easy. Remember, though, when you were a kid? Those books you pored over about dinosaurs or volcanoes or the sky at night? Remember your first visit to the Natural History Museum, in South Kensington, or that experiment with the Van de Graaff generator you saw at the Royal Institution? Remember lying in the grass on a summer’s day and inspecting the cocoon of a six-spot burnet? No, wait. The last suggestion is probably too specific: one of my memories masquerading as a common one. For all I know, there are no more six-spot burnets left in Britain.

My point is that feeling wide-eyed is a condition of childhood. For us, at childhood, the world feels like a miraculous place: somewhere to be amazed by. But then, of course, we grow up. And it all goes. The sense of wonder. The raw joy of discovery. And no number of escapes to a beach in Thailand to swim with the dolphins, or to a jungle lodge in Costa Rica to see a tapir, can ever fully awaken the eager amazement that filled you as a child.

I mention all this because it seems to be what Mark Dion’s art is principally about. For the past 30 or so years, in a career that has seen him present his installations and sculptures at an impressive assortment of contemporary art museums, from the Tate Gallery to MoMA, Dion has been remembering his childhood in a series of works that target the sense of wonder and the yearning for it we carry about as adults. Why is David Attenborough always on the telly? Because he connects us to something profound.

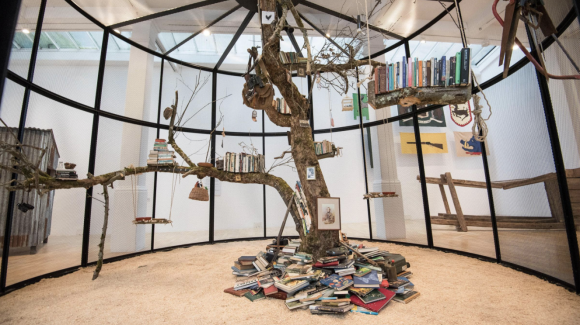

Dion’s show at the Whitechapel Gallery begins with an aviary. It’s round and purpose-built. Inside is a sprawling tree, with a flock of live zebra finches tweeting happily from its branches. The birds skip from twig to twig, and from book to book, because the aviary is home as well to a library of tomes, squeezed between the boughs and stacked around the trunk. The books range from colourful volumes of natural history to the letters of Carl Jung and the collected Foucault. So they have about them an upper-cased sense of knowledge.

The aviary can be walked through. So in you go, to dodge the birds, observe the books, notice things. See that photograph of a young Victorian pinned to the tree? That’s the young and beardless Darwin. See the old boy up in the branches? That’s Hitchcock when he directed The Birds.

An explanatory text, introducing us to the show, has a quote from the artist: “I imagine my viewers for the installation works, follies and sculptures as detectives at a crime scene.” He wants us to make connections and explore possibilities. So here is what DC Januszczak thinks Dion’s aviary — The Library for the Birds of London, to give it its proper name — is about.

I think it’s about the bad things we have done to our sense of wonder. How we have codified it, tamed it, betrayed it. The aviary isn’t just a prison for the birds. It is also a prison for all that knowledge in all those books. I don’t imagine it’s an accident that the cage is shaped like the round Reading Room at the British Museum, in which Karl Marx wrote Das Kapital. Over the course of the show, which runs until mid-May, those zebra finches are going to shower every book in there with bird shit. Whether you are Marx, Foucault or Desmond Morris, your fate is to be pooed on from a height. That is what the modern world does to us. It despoils us. It despoils our knowledge.

And that’s not all, m’lud. While wandering through Mr Dion’s installation, I could not help but notice that the tree in the centre, the one covered with books, is an obvious reference to the Tree of Knowledge, the one in the Garden of Eden from which Adam and Eve were not supposed to pick any fruit. But they did. So God chased them out. And we’ve been expelled from Paradise ever since. That’s why we can’t get enough of David Attenborough on the telly, m’lud. All those finches tweeting in the branches of Mr Dion’s aviary can be seen as a banal shorthand for the natural paradise from which we have been expelled.

Judge: “DC Januszczak, you’ve been watching too much Miami Vice.”

DC Januszczak: “M’lud, I’m absolutely certain the aviary has a biblical underpinning.”

Beyond the aviary, the show consists of half a dozen ambitious installations, all broadly concerned with themes of wonder, nature and knowledge. All are for wandering through and guessing meanings. All have an atmospheric dankness to them: a sense of loss.

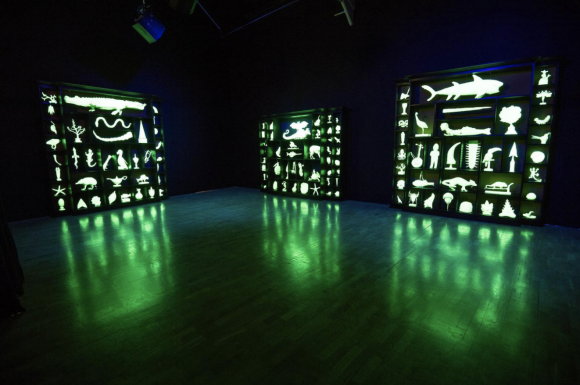

Downstairs, there’s a set of “blinds”, homemade shelters from which hunters can shoot their prey, of the kind you find scattered about the forests and marshes of Austria. Upstairs, there’s a nocturnal Cabinet of Curiosities, in which a set of busy shelves is filled with an eerie mix of natural wonders glowing in the dark, like those strange beasties you find on the ocean floor.

The most atmospheric installation, called The Bureau of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacy, was made in 2008 for the Manchester Museum. It’s an inch-perfect recreation of a cluttered study: a scholarly mess of curiosities and artefacts, stuffed birds and statues, battered books and scientific instruments. Strange objects are having surreal encounters with other strange objects in a lucky dip of fusty knowledge. If you’ve seen Sigmund Freud’s study in Hampstead, or any of the Indiana Jones movies, you will immediately recognise the aesthetic being mimicked.

And that is the problem with all this. It’s too familiar. You don’t have to be a detective to recognise these moods. They are the Gentlemen’s Library moods that are searched for in every episode of Salvage Hunters. Gaze into a shop window at Selfridges and you’ll find them in their crudest form. Go to Soho House and you’ll see them at their most expensive. Poor Mark Dion has been cruelly overtaken by the forces of fashion.

Thirty years ago, when he began mining these particular atmospheres, he was ahead of the times. By reflecting on our taste for wonder, by making art out of taxidermy and leather armchairs, he was paying serious homage to the natural history museum and its poetic framing of knowledge.

At exactly the same time, Damien Hirst was doing the same thing: floating sharks in formaldehyde, presenting rows of stuffed fish in glass cabinets. But where Hirst moved on and infused his work with satanic darkness, Dion has stayed put. His art hasn’t changed enough.

Battered suitcases and monkey skulls, mounted antlers and cased pike — this is art displaying the same taste for vintage natural history as an interior designer working on a cocktail bar in Shoreditch.