One of the great joys of being a wizened old art critic is that you don’t have to go to the cinema to see Clark Kent pop into a phone booth and become Superman. In fact, you don’t even have to go out. All you have to do is settle down in a comfy armchair with a pile of old catalogues and watch the reputations of artists changing outrageously before your eyes as different generations come up with different versions of the same creative. Oh, how we wizened old art critics giggle and gawp at the exciting costume changes and surprising plot flips that you encounter when you flick through a tower of old catalogues.

It works best with artists who already have bold outlines — the Leonardos, the Caravaggios, the Van Goghs. Picasso is an especially busy shape-shifter, but even he can be outnumbered. If you want to see Clark Kent turn into Dr Strange, then Daredevil, then Albert Steptoe and, finally, Wonder Woman, get yourself a box of popcorn and a selection of catalogues devoted to Amedeo Modigliani.

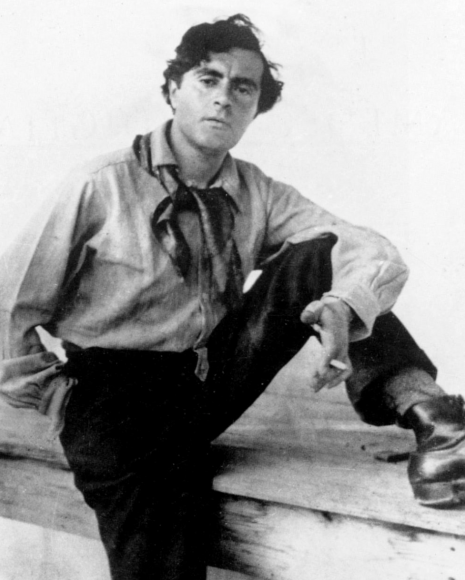

No one in art has survived as many identity changes as Modigliani, wild dog of Montparnasse, demon opium puffer and unstoppable dropper of trousers. Michael Kimmelman arrived at the perfect list when he described him in The New York Times as “the prototypical handsome, promiscuous, inebriated, pugnacious, misunderstood, tragically ill, impoverished, vulnerable, gifted and short-lived exemplar of la vie de bohème”.

It’s all true. The box Modi came out of is the Byronic one labelled mad, bad and dangerous to know. But the really puzzling thing about him is that none of this extreme waywardness shows in his work. He may have been an absinthe-sucking crazy, but his art remains steadfastly tranquil and still; full of silence and grace. Those famous madonnas of his, the swan-necked beauties with the oval eyes, glow with a transcendental light that feels like the opposite of decadence. There’s something ancient about them, something traditional and sacred. While the rest of bohemian Paris was tearing up reality and reassembling it in mad cubist jumbles, Modigliani, the wildest of the lot, was calmly returning to the ethereal grace of the 14th century.

It was Robert Hughes, the grumpy Australian naysayer, who supplied the definitive Modigliani put-down when he dismissed him as a peddler of “modern art for people who don’t much like modernism”. Ouch. It’s why critics have never really taken to him, and why the public always has. It’s also why he has had so many shows devoted to his work — ordinary people queue to see it — and why the mammoth Modigliani exhibition that is thundering towards Tate Modern is sure to be packed to the rafters. So book early.

With almost 100 paintings and sculptures in it, this will be the largest Modigliani survey mounted in Britain. And from my perusal of the pre-emptive paperwork, the redrawing of his outline that is taking place here is going to be especially hopeful. Because the new Modigliani promised to us by the Tate is going to be female-friendly, a supporter of girl power and a useful gateway through which a powerful assortment of independent women made a telling entrance onto the world stage. The feminist Modigliani: now there’s a turn-up.

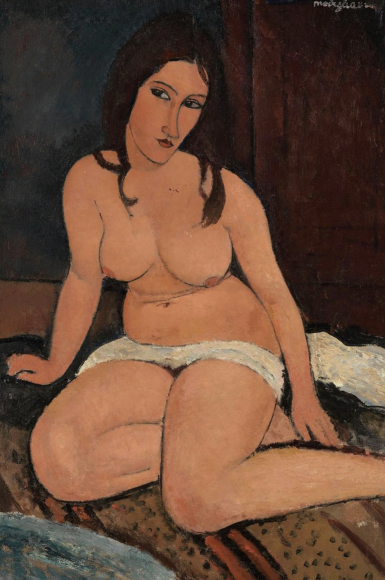

And that’s not all. The show will introduce us, as well, to the digital Modigliani, with a virtual-reality recreation of his last Parisian studio, through which you can wander, free as a cloud, in an all-action Modigliani headset. Also included will be the most comprehensive selection of the pictures that caused a rumpus at his only one-man show in 1917: his nudes. Unfortunately, the gallery staging this momentous display was located across the road from a police station.

One day, the chief of police popped out for lunch and noticed that the naked brunettes in the gallery window were not depilated, as nudes in French art usually were. Instead, they sported pubic hair that was, as Robert Hughes noted, “as neatly topiarised as Hercule Poirot’s moustache”, with further offending tufts under their arms. “They have hair,” the police chief is said to have squealed before insisting they be removed.

So yes, Modigliani at Tate Modern promises to be a shape-shifting event. But before we meet the new Modigliani, allow a wizened old art critic to fondly remember the old one. The Modigliani I grew up with was not digital, or feminised, or a gateway for powerful and independent women. My first Modigliani was a sex-craved cad addicted to cocaine and hash who spent most of his creative life in a state of toxic befuddlement. Ah, the good old days.

He was born in 1884 in Livorno, the battered Italian port that you sometimes end up at if you take a wrong turning in Pisa. Livorno has some decent Renaissance ruins and a good reputation for seafood, and that’s about it. Even its old English name — Leghorn — is lacking in grace. Modigliani is easily the most thrilling thing to have come from there.

The first of the remarkable women who stud his life — empowered woman No 1 — was his mother, Eugénie Garsin, who came from an illustrious line of Sephardic Jews and claimed to be descended from the 17th-century Dutch philosopher Baruch Spinoza. Eugénie doted over her son because he was the sickest and weakest of her children, and because there was something strangely fated about him.

The Tate show isn’t much interested in Modigliani the Jew: it’s one of the versions being ignored here. But when he met new people in Paris, he would often introduce himself with the salutation: “I am Jewish.” So it definitely meant more to him than it does to modern curators.

The story of his birth is equally charged and curious. According to family legend, the day he arrived was the day that the bailiffs came round to the Modigliani house to seize all their possessions. A series of bad business decisions had seen the Modiglianis go bankrupt. However, an ancient Italian law forbade bailiffs from seizing the bed of a pregnant woman, or a woman in childbirth, so the family piled all their valuables onto Eugénie and the newly arrived Amedeo, and his fortuitous birth saved them.

It’s a cracking origin myth. And probably explains his name. Amedeo means something like “loved by God”. From the start, his mother singled him out for special attention, and even by Italian standards he was a mamma’s boy. So fragile was he that he never went to school, and was taught at home till he was 10. At 11, he contracted pleurisy. Three years later he got typhoid fever. Two years after that he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, the disease that never left him. Eugénie responded to the sicknesses by spoiling him rotten, and taking him on long cultural journeys to Naples, Rome, Florence and Venice, where she educated him in the delicacies of Italian Renaissance art and awakened the desire in him to be an artist.

Opinions vary about his adult height. Some say he was only 5ft 3in. Others enlarge him to 5ft 5in. But he was certainly diddy, though perfectly formed. In his cafe years in Paris, a favourite party trick was to drop his trousers, lift off his shirt, and stand there naked, shouting: “Am I not a god?” But real gods don’t suffer from tuberculosis for all of their adult lives, or die from it at the age of 35.

A couple of Modiglianis ago, the view began to be aired that his furious drug taking and drinking were actually a cover for his illness. Fearful of scaring away friends and lovers with his tuberculosis, he hid the real reasons for his coughing and his unsteadiness by feigning an uncontrollable appetite for intoxicants. It’s an explanation that is tempting to believe, until you encounter the descriptions of him left behind by his lovers. Beatrice Hastings, the bisexual English poet who shared her bed with him in Montparnasse, having previously shared the writer Katherine Mansfield’s bed in London, bashed him up in her memoirs as “a craving, violent bad boy, overturning tables, never paying his scores and insulting his best friends”. During arguments, he would throw her, head-first, out of the window. She, to her credit, did the same to him.

The Tate show will not be going into any of these notorious madnesses of his. It’s not that kind of event. Instead, it will ignore the wilder details of the Modigliani legend and replace them with something less purple and more contemporary by examining such au courant topics as his relationship with French cinema. It’s a fresh angle. Totally today. But nowhere in the big chunks of Modigliani literature on my shelves is any mention actually made of cinema. Modigliani himself never noted it, and there are no signs of it in his work. So good luck with that.

What there are signs of — big ones — is the influence of early Renaissance art: the ethereal touches of Piero della Francesca, the slight madonnas of Fra Angelico, the faded clarity of Carpaccio. In 1903, having previously attended life classes at the Free School of Nude Studies in Florence, the handsome sickling from Livorno registered to study at the Regio Istituto di Belle Arti in Venice. Armed with a copy of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra thrust in his back pocket, Modi, as they called him — a homophone for the French maudit, meaning “cursed” — spent three years in Venice learning how to be decadent. He dabbled in the occult, began smoking hash and collected his first girlfriends. No wonder the plaque they have put up on the side of his old house on the Fondamenta San Basegio, directly opposite the Veronese-filled church of San Sebastiano, cockily insists: “In Venice I received the most valuable lessons of my life.”

By the time he arrived in Paris in 1906, aged 22, he was pretty close to the finished article. Coughing incessantly, smoking incessantly, drinking incessantly, dashing off rapid drawings that he sold to passersby in the street for whatever they could spare, he was, according to his new buddy Picasso, the “one man in Paris who knows how to dress”. In his brown corduroy suit set off with a yellow shirt and a scarlet scarf, or a black velvet jacket splattered picturesquely with oil paints, he looked like the young Marcello Mastroianni, and few women could resist him.

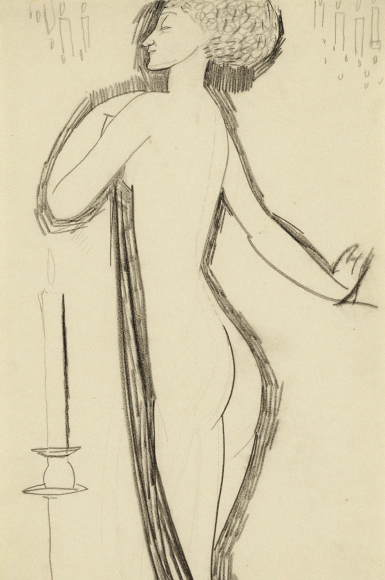

His first studio was the squalid Bateau-Lavoir in Montmartre, where, at exactly that moment, Picasso and Braque were inventing cubism. It was a momentous artistic discovery — one that Modigliani completely ignored as he set about becoming a sculptor of tall, thin female heads. Persuaded by his friend Jacob Epstein, another peripatetic Jew, that sculpture was the most serious of the arts, he scavenged for stones on the building sites of Paris and carved them into idols that seem simultaneously ancient and modern.

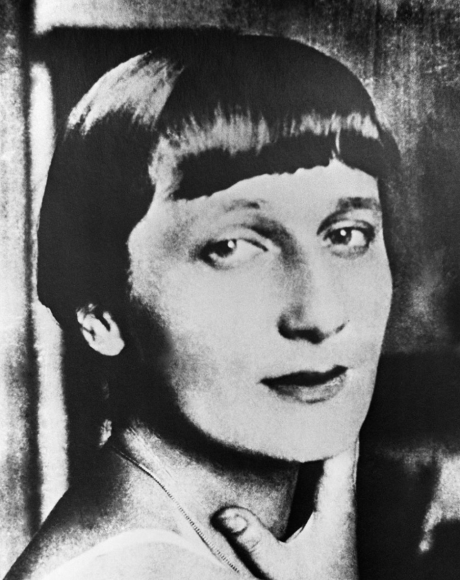

At night, remembered Epstein again, Modigliani would put candles on his etiolated heads and worship them, and the two of them would hatch absurd plans to build a full-size Temple of Beauty. The lovely drawings he made of female caryatids were beautiful supports imagined for the temple’s roof. And it was about now that empowered woman No 2 entered his life: the brilliant Russian poet Anna Akhmatova.

For proof of how strange are the ways of love, and how unfair, you could not ask for clearer evidence than the relationship that ensued between Modi and Anna. She was on her honeymoon in Paris when she met him, having recently married her energetic fellow scribbler Nikolai Gumilev, who had pestered her for years to wed him and whose persistent encouragement had originally persuaded her to become a poet. But poor Gumilev didn’t have what Modi had.

Returning briefly to Russia, within a year Akhmatova was back in Paris, where she posed for around 20 Modigliani paintings, including several scintillating nudes. You will see some of them in the show, elegant depictions of an elongated woman whose magnetism was as legendary as her snippiness. This is what she had to say about the unfortunate Gumilev when she left him:

“He loved three things in life:

Evensong, white peacocks

And old maps of America.

He couldn’t stand bawling brats,

Or raspberry jam with his tea,

Or womanish hysteria.

… And I was his wife.”

All her lovers had poetic stilettos plunged into their hearts. Except Modi. Until the end of her days she kept a nude drawing he made of her above her settee. And when she did write about him, it was with cheery fondness. “When you’re drunk, you’re so much fun”, she smiled, in the best-known of her Modigliani poems.

Tiny as he was, Modi attracted tall and forceful women. Akhmatova towered over him. So did empowered woman No 3, the already-mentioned Beatrice Hastings. Born in South Africa in 1879, she was significantly older than him, previously married, previously aborted and previously bisexual, and had fetched up in Paris just before the outbreak of the First World War.

Another of the books he liked to carry around in his velvet pocket was The Divine Comedy, by his beloved Dante, so he must surely have seen the arrival of a Beatrice as a sign. In fact, her real name was Emily Haigh, but Hastings was another inveterate swapper of identities and throughout her long literary career she came up with dozens of different appellations for herself.

In England, she had been the artist Wyndham Lewis’s lover as well as Katherine Mansfield’s, and by the time she got to Paris she had a substantial literary career behind her editing and contributing to The New Age, where she commissioned and encouraged writers of the size of TS Eliot and Ezra Pound. When she began her angry romance with Modigliani, she lied about her age. She was five years older than him, but he never suspected.

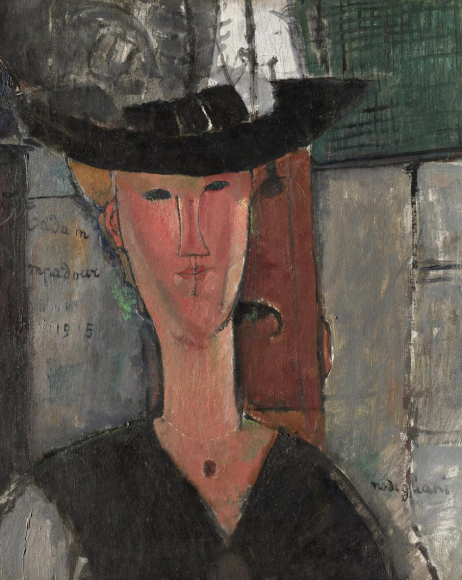

So she was slippery. And his portraits of her seem to jump around more frantically than his portrayals of anyone else. There she is as a bright blonde, sporting a bold black hat in a picture he inscribed “Madame Pompadour”. And there she is again, looking enticingly Spanish, shiny black hair parted severely in the middle and a sexy ribbon around her neck.

It was Hastings who seems to have reignited Modigliani’s edgy relationship with the occult. Ever since his sojourn in Venice, he had nursed a taste for other realities. The relentless puffing of hashish must have played a role in that, as did the smoking of all that opium. And although he had stubbornly avoided joining any of the isms clamouring for aesthetic attention in Paris at the time, the one art style with which he did express some solidarity was symbolism: the ism of choice of the hardened ether-sniffer.

Drugs will have played a part, but so did theosophy, the cultish pseudo-religion invented by the fraudulent Russian medium Madame Blavatsky, which was sweeping through art circles at the time and which Hastings was later to defend in a series of shouty pamphlets. Having attempted on several occasions to read Blavatsky’s magnum opus, The Secret Doctrine, and quickly given up, I cannot claim to be more than a dumb amateur when it comes to understanding these impossibly dense occult ramblings. All I can pass on with any confidence is that theosophy proposed a common origin for all religions and that it encouraged its adherents to peer through the superficial surfaces of reality to discern the bigger and truer reality below.

This notion, that what you see is not what is really there, was massively influential. It legitimised abstraction and changed art. Mondrian was a theosophist. So was Kandinsky. And so, to some degree, was Modigliani in his Beatrice Hastings phase.

I dwell on it here because it seems pertinent to the most pressing of the Modigliani questions. Why does his art exude such spiritual calm when its maker was such an unstable crackpot? Why do his sitters stare so vacantly through such pupil-less eyes? Are they staring in or out?

These are the mumblings whose volume will be turned up when the display finally reaches the shy and lovely presence of Modigliani’s last and greatest muse, the impossibly tragic Jeanne Hébuterne. Is there a sadder or more doomed presence in art? Off the top of my head, I cannot think of one. She was 19 when they met at the Académie Colarossi. He was 32. She wanted to be an artist, and he just wanted her.

With her perfect oval lines and her pale, butterfly presence, Hébuterne is the archetypical Modigliani woman, and the subject of his most tender portrayals. Over and over again he painted her, each ethereal likeness more haunting than the one before. She bore him a daughter, and would have borne him another if the tuberculosis that he contracted as a child had not abruptly killed him on January 24, 1920.

The next day, Jeanne Hébuterne, nine months pregnant, threw herself from the fifth-floor window of her parents’ apartment and ended her life as brutally as the tuberculosis had ended his. So no, she wasn’t one of his empowered women. And Modigliani at Tate Modern will be too sensible an event to shed a tear for the broken love shared by Modi and Jeanne. But that doesn’t mean the rest of us can’t.

Modigliani, Tate Modern, London SE1, from Thursday until April 2; tate.org.uk.