When I was a kid, I could not wait for my mum to stop talking about Russia. She was a stuck record on the subject. It took nothing to set her off and, once she started, on and on she went with the same dank stories. How the Russians invaded her village in Poland. How they put her on a cattle truck when she was 14 and transported her to Siberia, where they forced her to work in a labour camp. How eight of her family went to Siberia, but only five came back. How cold it was. How frightened she was of the wolves. I heard it all so often, I practically knew it by heart. But it wasn’t until this year that I properly felt its heft.

As you know, 2017 is the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution. To commemorate, scores of Russia shows up and down the land have dealt in various artistic ways with this huge historic memory. Earlier in the year, the Royal Academy gave us a lively mix in which progressives and repressives were jumbled up, as if they were essentially the same thing.

Now Tate Modern, which has been slow to the party, has finally got there with two cool shows that ruminate calmly upon recent Russian history. Too calmly for my new tastes. What they need here is a couple of babushkas sobbing in the corner about the loss of their sons and daughters in a gulag. Failing that, how about a hologram of my mother in the Turbine Hall, repeating her Siberia stories?

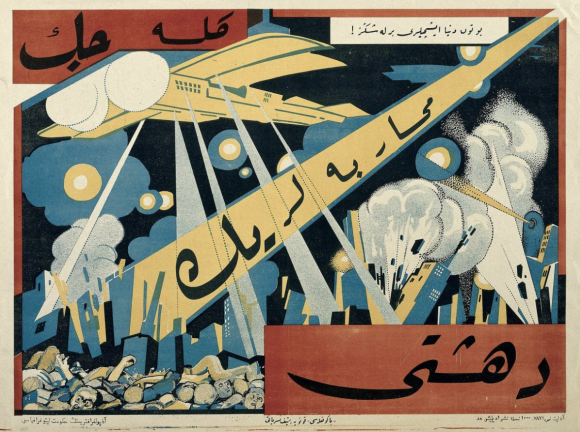

Red Star over Russia is a collection of posters, films and photographs produced during and after the revolution. Basically, it’s the story of the Soviet Union, told briskly and cheaply through a busy selection of the popular arts.

What posters have, and paintings do not, is a connection with the populace that privileges legibility. The shouty images that pack the first room are trying to fire up a populace that was largely illiterate. It wasn’t a time for subtlety. The unknown graphic artist remembering Bloody Sunday in 1905, when the tsarist forces massacred unarmed protesters on a St Petersburg square, does it by showing the square filled with skulls, and by colouring them red.

As if to prove that subtlety is often a waste in the world of posters, also included is a marvellous abstract lithograph by El Lissitzky of a red triangle thrusting into a white circle. It’s an abstract evocation of the civil war between the Bolsheviks and the White Army that broke out after the revolution, and as art, I love it. But as a political poster, it must have baffled more than it informed.

Everything here comes from the collection of David King, formerly of this parish, as he was once the art editor of the Sunday Times Magazine. A crazy collector of Russian materials, King, who died last year, ended up amassing an archive of 250,000 examples, of which this is a fraction.

King was initially drawn to the Russian popular arts, I read, by the notorious treatment of Trotsky and the way he was “airbrushed” out of Soviet history. As an art editor, he recognised the issue and was fascinated by it. A wall here filled with different versions of the same photograph shines a bright light on the process.

In one photograph, Trotsky stands next to Lenin on a pedestal in Moscow. In the next photograph, he doesn’t. He’s been Tippexed out, reframed, disappeared. Even more starkly, what begins as a group portrait of Stalin and three of his allies ends up as a solo portrait of the great leader. One by one the others are photographically picked off, as if by a sniper.

All this is presented to us in the usual Tate fashion as a sequence of thematic displays — mini exhibitions with a specific focus — arranged in a loose chronology. We start with the revolution and end with the death of Stalin. By revisiting events through the popular arts, the hope here is to present a truer picture than the one you get higher up the art ladder.

But I’m not sure that you do. What’s missing, what you don’t get in the popular arts, is the ringing voice of an author insisting upon the truth: you don’t get Solzhenitsyn. Instead, and this is the persistent weakness of thematic displays, the materials are arranged by curatorial whim.

Thus the section devoted to the couples who worked in the popular arts — Rodchenko and Stepanova; Klutsis and Kulagina — feels as if it is more concerned with 21st-century issues of equality and gender identity than with the startling creation of Stalin’s image taking place on the walls. By pointing to the couples, the curation points away from the pachyderm.

We see it again in the final room, devoted to notions of the Motherland. During the Second World War, the Russian soldiers fighting on the eastern front were roused into greater effort by images of their womenfolk encouraging them to resist. Posters of the great leader gave way to posters of mothers and wives in need of protection.

It’s interesting stuff, but it feels more like an enlarged detail than a concluding chapter. These themed Tate displays deal with the icing rather than the cake. Shorn of context, shorn of plangency, shorn of tears, Red Star over Russia is a selection of engrossing bits searching for a meaningful storyline.

Over on the other side of Tate Modern, in what they call the Boiler House and I call the old bit, the veteran husband-and-wife team of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov update the Russian story to the present day with a retrospective of their sneaky, snippy, slippery installation art.

Grasping what the Kabakovs are saying is like trying to knot an eel. They use lots of texts in their work, so unless you are a fluent Russian speaker, you will spend significant slabs of their show staring hopelessly at large expanses of the Cyrillic alphabet. Their jokes are chiefly about Soviet days as well, and depend on knowledgeable readings of the details. So that too is an obstacle.

The biggest reason why the Kabakov show is such a tricky beast, however, is that Russian artists are world leaders at not saying what they mean. It’s something they imbibe with their mother’s milk: an instinct for preservation that allows them to comment on the world they are in without the world they are in knowing they are doing it.

Installation art is especially handy for this, as it conveys its meanings with nudges and winks. The famous Kabakov piece The Man Who Flew into Space from His Apartment consists of a recreated Soviet room from which an unseen inhabitant has launched himself into orbit with a homemade catapult that hangs from the roof. Made in 1985, it’s intended, I suppose, as a sarky commentary on the space race. But there’s something bleaker here as well — a nihilistic encapsulation, perhaps, of the hunger for freedom and the will to escape.

Another giant installation features the entire back end of a train, from which is spilling an assortment of painted canvases. It’s called Not Everyone Will Be Taken into the Future and concerns itself, I think, with the idea that some artists make it, but others do not. Also intended, I suspect, is some kind of existential rumination upon the hopelessness of life and the random workings of fate. But that could just be wishful thinking on my part.

And that’s the trouble with installation art in general and Russian installation art in particular. The damn stuff keeps handing you back the responsibility and refusing to say what it means. In English, comrade, it’s called passing the buck.

Red Star over Russia, until Feb 18; Ilya and Emilia Kabakov, until Jan 28; Tate Modern, London SE1