Have you noticed how you never quite know where you are with Italian futurism? I certainly have. It was surely the most idiosyncratic, even wacky, of the pioneering movements of modernism. Something about the union of Italy and 20th-century progressiveness didn’t quite work.

In theory, the aims of the futurists appear clear enough. They were seeking to evolve a pictorial language with which to convey the changing rhythms of the modern world. “A roaring car that seems to run on grapeshot is more beautiful than The Victory of Samothrace,” shouted Marinetti, famously, in the Futurist Manifesto of 1909. They wanted to capture the sensations of speed, electricity, dynamism. The old art couldn’t do it. The new one could.

That’s the dream. The problem is that the actual pictures and sculptures the futurists produced seem so often to be about something else. Even a brief poke of the head around the corner of the strange Giacomo Balla exhibition at the Italocentric Estorick Collection, in Islington, should be enough to convince most visitors that Balla, the famous futurist, was barely a futurist at all.

Early in the show, we encounter Tolstoy, of all people, looking especially bearded and weighty. Balla painted him in 1911, two years after the publication of the Futurist Manifesto, but not an atom of futuristic ambition is discernible in the great sage’s wrinkly and biblical presence. The more promising Iridescent Interpenetrations, of 1913 — brightly coloured abstract lozenges, worked out with recurrent geometry — have no sense of movement or thrust to them. They are pretty cosmic patterns of the sort you might find on Islamic cloth or tiles.

Thus, the first and ultimately most insistent message delivered by this strange show is that Balla (1871-1958) needs to be understood differently from the way he is usually understood. The career laid out for us in a bitty selection drawn from the collection of the posh Italian fashion designer Laura Biagiotti — best known these days for her range of expensive perfumes — is a career of whimsy and wilfulness. Already touching 40 when Marinetti unleashed the futurists, Balla, you feel, was a piece of loose paper, waiting to be picked up by every strong wind that passed his way. And some of those winds blew in regrettable directions.

Our first encounter with him, in 1895, finds him painting a lonely girl sitting in a dark Italian corner, sewing thoughtfully in the shadows. She’s the first of the vague female presences that keep returning to these walls, the last of them painted in 1934, when Balla was going through his fascist phase as a supporter of Mussolini. From beginning to end, there’s something off-putting about the absence of real personality or character in his idealised women.

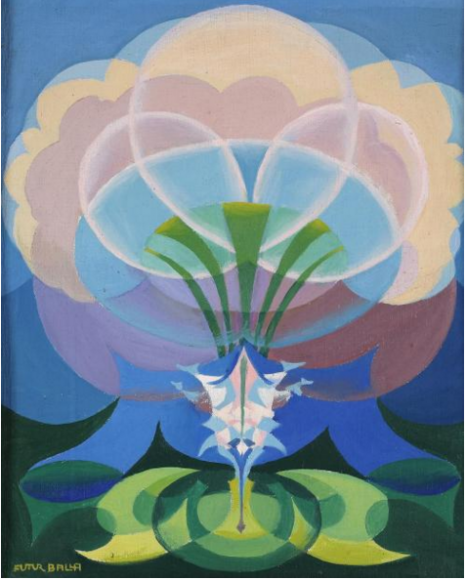

Though Balla never rises above the passable as a figurative painter, he becomes more exciting when he turns to futurism and abstraction. The Biagiotti collection contains none of his futurist masterpieces, but it is packed with scraps and snippets of his experimental progressiveness. Futurfishes, from 1924, shows a triangular ocean filled with triangular fish: if God had used a ruler, this would be our world. Expansion of Spring, from 1918, is a cosmic flower shape that spreads spookily into the sky like an atomic cloud designed by Buddhists.

It’s weird art. None of it appears at all interested in speed or machines. Rather, it seems to be trying to imagine a new cosmic order. Before he was a fascist, before he was a futurist, Balla had been an occultist — a theosophist and a freemason — and it is in the dreamy spiritual hocus-pocus of theosophy that we probably need to search for his primary drives. Even the peculiar way he keeps switching modes, from figurative art to abstraction and back, feels governed by ambitions located in the fourth dimension.

The second half focuses on his work as a designer and features examples of his clothes, furniture and domestic interiors. Most exist only as drawings and plans. A few have become finished products. All try to rip up the antique way of designing things and to come up with a fresh one.

It’s a more coherent display than the muddled opening stages, but just as Balla the figurative painter never fully convinces, neither does Balla the futuristic designer. Making men’s suits triangular and pointy gives them a preternatural Dan Dare air, but saddles them, also, with extreme unwearability. As for the impractical child’s room designed for Iris Calabria in 1932, there are enough sharp edges on its protruding corners to murder a classload of kids.

I entered this display unsure what I thought about Balla. I left it slightly scared. Imagine if Mussolini had won and the wearing of Balla’s suits to work had been made compulsory. Shiver!

At Blain/Southern, the reliably dark and fascinating Mat Collishaw is dark and fascinating in a spooky show called The Centrifugal Soul. Ever since he came to prominence in the late 1980s with a giant close-up of a bullet wound in someone’s head — one of the signature works of Brit Art — Collishaw has prowled around the nether regions of the human experience, searching for evidence of our fall. If he were a type of bird, he would be a quothing raven.

The present event is dominated by modern versions of two celebrated examples of Victorian optical trickery: the zoetrope and Pepper’s ghost. The zoetrope was an early form of animation, achieved with spinning imagery and strobe lighting. In this instance, it gives us a giant bouquet of tropical flowers, around which dances a mad array of exotic birds: mostly birds of paradise, famed for their courtship displays and their look-at-me mating plumage. It’s like a model in a natural history museum, acting out the behaviour of the birds and the bees. But it does so with an air that is harsh and ceaseless. Look how mechanical the rumpy-pumpy has become in paradise today.

Pepper’s ghost was an illusion achieved with mirrors and hidden compartments that seemed to project a ghostly figure into an adjacent room. Here, the trick is used to transport the famous Major Oak, one of Britain’s oldest trees, in whose hollow trunk Robin Hood is said to have hidden, from Sherwood Forest to Collishaw’s show.

Huge, gnarled, twisty, doomy, the hollow oak turns slowly, as if in its final asthmatic revolution. Something is being said about the nature of modern Britain, you feel. And it isn’t very complimentary.

Giacomo Balla, Estorick Collection, London N1, until June 25; Mat Collishaw, Blain/Southern, London W1, until May 27