Art has an excellent history of turning insults into badges of honour. It happened, for instance, with the cubists, who were dismissed in the reactionary French press as painters of cubes, but who disarmed their enemies by adopting exactly this term as their nom de guerre. Earlier still, we had those daring expressionists — Matisse, Derain, Vlaminck — whose mad brushstrokes unsettled the bourgeois so fully that they were accused of painting like wild beasts, or fauves. So the fauves they stayed.

Exactly the same has happened to the word “queer”. Until the 1980s, it was used almost exclusively in a pejorative sense to describe gay men and women. As an insult, it could be found scrawled on lavatory walls or shouted from the doorways of pubs at passing strangers on St Martin’s Lane. A tough, harsh, Germanic little word, “queer” had an onomatopoeic ring to it that made it sound especially aggressive when directed at others. By appropriating it as a mantle, the queer community has successfully turned self-defence into attack. As Derek Jarman put it: “For me, to use the word ‘queer’ is a liberation; it was a word that frightened me, but no longer.”

This, then, is the etymological background to Queer British Art 1861-1967, a display at Tate Britain that has set out to recognise the contribution made by queer artists between the years 1861, when the death penalty for sodomy was abolished, and 1967, when sex between consenting men was finally decriminalised. The century under examination is, therefore, an era of gigantic social change — from the Victorian age to the Swinging Sixties, with two world wars thrown in for good measure.

This thunderous historical reality seems to hover beyond the show’s sightlines, however. The centre stage, meanwhile, is occupied by a floaty atmosphere of flux and uncertainty, whispers and innuendo, half-truths and projections.

One thing is certain: without the queer contribution examined here, the arts in Britain would be catastrophically impoverished. From Francis Bacon to Virginia Woolf, from David Hockney to Radclyffe Hall, from Oscar Wilde to Noël Coward, homosexuals, and inbetweenies, have punched far above their weight in the creation of our culture. That’s the good news. The bad news is that identity politics are not the same thing as scholarship. Indeed, they are scholarship’s enemy when they privilege attitude over certainty. And from beginning to end, there is a tendency to flimflam and cross the fingers when it comes to defining queer artists or pinpointing the queerness of their work.

We begin with Simeon Solomon (1840-1905), a belated pre-Raphaelite who was Jewish and alcoholic as well as homosexual. Arrested in 1873 for attempted sodomy in a public urinal, Solomon ended up in a workhouse and died poor and forgotten. You would have thought a life as dark as his — the workhouses, the alcoholism — would have inspired a keener understanding of the issues and thrusts of Victorian modernity. But no. Instead, he became a painter of ludicrous mythological fantasies, in which England is transformed into a pretend Greece inhabited by toga-wearing daydreamers with wistful eyes.

The real scandal of Simeon Solomon was not that he was caught in flagrante in a public lavatory in 1873, but that in 1894 he was still painting pictures as asinine as The Moon and Sleep — beautiful goddess falls in love with beautiful shepherd under a beautiful night sky. To put this anachronistic waffle into context, we should remember that at exactly the same time, in Norway, Edvard Munch was painting that nerve-jangling, accusatory embodiment of modern anxiety, The Scream.

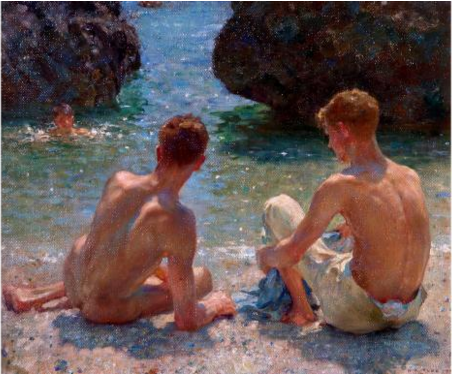

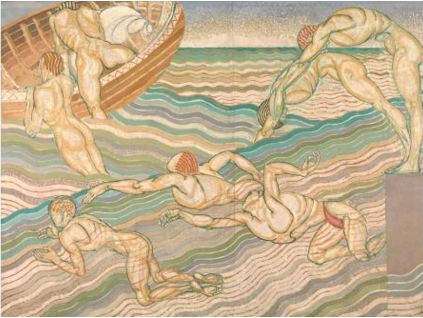

Solomon was no worse in his absurd imaginings than the other pre-Raphaelites. Indeed, the show’s opening stretches are filled with examples of the dodgy ancient fantasies churned out in Britain in the age of the train, the factory and the suspension bridge. To get into this display, it seems to have been enough that you painted half-clothed Athenian youths or drooping waterside nymphs. On those shaky grounds, all the pre-Raphaelites could have been included.

And that’s the problem with cultural politics. By replacing the hard work of proper scholarship with the easy option of assuming a theoretical position, they ensure that bad art is no longer recognised as bad art. All the way through we are offered feeble examples. Even the Bacons inserted at the end are only average Bacons. Too much is included for gossipy reasons. And some of the art isn’t art at all.

Thus, in the section on Oscar Wilde, we suddenly encounter the battered door of his cell in Reading gaol, hung piously on the wall in the manner of a medieval relic. What are we supposed to do? Worship it? And see the bright red robe glowing in that spotlit vitrine? That’s one of Noël Coward’s dressing gowns. Yes, his actual dressing gown.

Though the show claims to be examining the full spectrum of queerness, it is overwhelmingly dominated by the efforts of gay men. The theatre section that follows the pre-Raphaelite fantasies is essentially a collection of memorabilia and gossip, with lots of photographs but precious little insight. A potentially fascinating display case full of theatrical dames and cross-dressers introduces us to the curious British phenomenon of “the man in drag as family entertainer”, from Danny La Rue to Mrs Brown. But having shown us the photos, the shows darts on to its next bit of gossip.

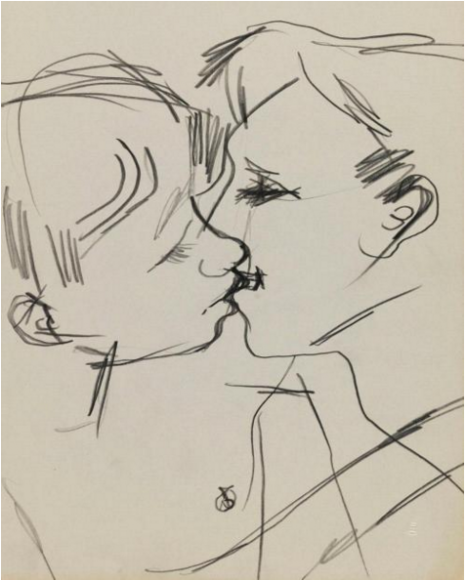

It’s a failing that culminates, alas, in a central gallery devoted … zzzz … to the Bloomsbury set, “who lived in squares, painted in circles and loved in triangles”. With their tiresome bed-hopping and third-rate pseudo-French doodling, the Bloomsberries are familiar Tate fodder. No amount of showing or reshowing of Duncan Grant will ever turn him into anything better than he was: a feeble post-impressionist with rocks for fingertips. Grant’s sexual adventurousness may qualify him for inclusion here, but his talent does not.

While poor art is the show’s main failing, another is its tendency to see evidence of queerness under every stone. Or rather in every cactus. In Glyn Philpot’s Repose on the Flight into Egypt, painted in 1922, a faceless holy family has slumped at the edge of a pagan world, in which a looming cactus is said to be setting a homoerotic agenda. A few walls further, we are asked to notice how Philpot’s portrait of a man with a gun features a “firm grip on the gun’s phallic barrel that is possibly suggestive”.

This is the worst kind of art history: the projection of casual readings onto the past. The constant refrain of maybe/possibly/could be becomes a disqualifying factor in too many of the arguments. This spirit of approximation extends as well to the chosen artists. I love Claude Cahun’s work, and her show at the National Portrait Gallery with Gillian Wearing is currently one of the best in London, but Cahun is fully French. No amount of cultural hopefulness can qualify her for inclusion in Queer British Art.

Laura Knight, meanwhile, is appropriately British, but no trace of sexual ambiguity has ever attended her persona. To include her because she has painted a female nude in her self-portrait is to misunderstand her motivation.

A well-meaning effort, then. But an unsatisfactory show.

Queer British Art 1861-1967, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Oct 1