Venice. It’s mental. But I love it,” yaps Damien Hirst, bounding into his unbelievable new show about belief like an excited puppy arriving in a new room. “It’s psychotic as well. Great for art. The whole of Italy is great for art.”

Indeed it is. But when it comes to artistic craziness of the depth and wildness Hirst is now exhibiting, Venice has the edge over anywhere else on earth. Stupendous palaces. Crumbling walls. Everything floating inches above the water. No cars. Just boats. There are plenty of places where the demented assault on our notions of reality he has mounted would have felt demented. But Venice isn’t one of them. In Venice, craziness doesn’t feel crazy. And mad men do not always appear mad.

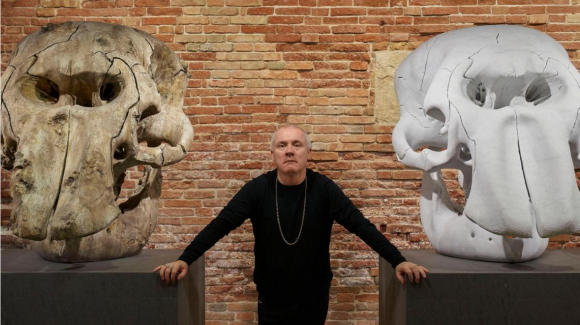

You will probably have heard something already of what he has been up to. Despite levels of enforced secrecy that would shame the CIA, hints and whispers have been fluttering about the art world for years. Hirst is planning something enormous. It’s going to be bonkers. It’s costing hundreds of millions of pounds. No one knew exactly what it was, but everyone knew it would be immodest.

On the surface, what we have here is the tale of a chap called Cif Amotan II, a freed slave living in Antioch at the end of the 1st century AD, whose vast acquired wealth allowed him to build a stupendous collection of 100 ancient artefacts, which he planned to house in a new temple. To transport them there, the 100 objects were loaded onto a ship called the Apistos, which, unfortunately, sank off the coast of Africa with everything on board.

In 2008, the wreck of the Apistos was rediscovered and Hirst, who had recently sold £200m of his art in a spectacular sale at Sotheby’s, stepped in to finance the recovery of the treasures. The result is what you see now divided between the exhibition halls of the enormous Punta della Dogana, on one side of the Grand Canal, and the huge Palazzo Grassi on the other.

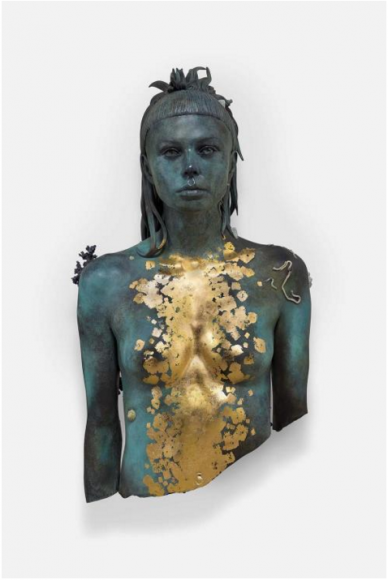

The 100 treasures come from all corners of the ancient world, in all shapes and sizes, and in various states. Some are covered in 2,000 years of corals and barnacles. Some have been cleaned up for the show. Some have become museum models that indicate how they must originally have looked.

They range from a statue of a headless demon that is fully three storeys high, and towers over the entire central space of the Palazzo Grassi like an indoor Eiffel Tower, to some pea-sized gold coins in a glass case tracing the history of money. There are weapons. Statues. Idols. Jewels. Buddhas carved out of jade. Unicorns carved out of rock crystal. All this Cif Amotan II collected in his mad and expensive pursuit of knowledge and power.

This background story is, of course, complete twaddle. A minor shuffle of letters tells us that Cif Amotan II is an anagram of “I am a fiction”. And those among you who read Koine Greek will know that Apistos, the name of the sunken boat, translates loosely as “Unbelievable”. Yapping about the pretence in his trademark happy-dog manner as we peruse what appears to be a display case filled with rusty swords, Hirst points to one that seems to have an ancient inscription on it. Peering closer, I make out the words “Sea World”. It’s one of Connor’s swords, he chuckles. Connor is his son. He has two others, Cassius and Cyrus. In the Hirst family, “C” is the letter of choice for boys.

Later we watch a film about the huge salvage operation to lift Cif Amotan II’s lost hoard out of the Indian Ocean, and Hirst encourages me to look at the logo on the divers’ suits. It says “CCC Salvage”. The suits are red. He designed them himself. That’s why he gave them bright yellow windpipes.

As for the colossus in the Palazzo Grassi — surely one of the biggest sculptures ever made, ancient or modern — he yanks out his iPhone and taps in “William Blake” and “The Ghost of a Flea”. Up comes a weird watercolour of an otherworldly demon painted by Blake in 1820. It’s the colossus, but a thousand times smaller.

So it’s all fake news — fake news that takes great delight in revealing its own falsity. Hirst himself is merrily at ease with the unreality of it all, and encourages me to describe the show as I wish. Do what you think is right, he instructs me. In which case, let’s not beat about the burning bush. It’s a mega-con. That’s obvious. What’s not obvious is why he has done it, and what he hopes to achieve by it.

If most exhibitions are the size of a suburban semi, Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable, as the monster is officially entitled, is the size of the Louvre. Make that two Louvres, one on either side of the Grand Canal. I reckon this insane voyage across the choppy waters of belief is the most ambitious solo exhibition any artist has ever mounted. Seriously. I cannot think of any previous event that matches the scale or cost of this one.

Given how many different people with different skills using different materials in different places were involved in its production — 250 craftsmen in five countries — the fact that none of us outsiders had much of a clue what was really going on during the 10 years the behemoth was being created is evidence of the world-class control freakery Hirst exerts over his exertions. Who paid for it? He did. “The galleries said to me, ‘Treat us like a bank.’ Then I went to them with the idea and they said, ‘Go to the bank.’”

We meet at the Punta della Dogana, the former customs house opposite St Mark’s Square that was turned into a museum in 2009 by François Pinault, Hirst fan and super-rich owner of Christie’s, Gucci and Converse. In fact, we meet in the most moneyed corner of this moneyed corner — the gold room.

Gold is one of my favourite art substances. Not for nothing did the Incas call it “the sweat of the gods”. Every society prior to our own has treasured gold in ways that are profound and clinging. We, alas, have presided over its cultural cheapening and engineered its Ratnerisation. It’s a transformation Hirst is hoping to reverse, and in this ambition, he has my undying support. If you don’t get gold, you don’t get life.

Walking into Cif’s gold room is like walking into the Gold Museum in Peru. Bring your shades. There are amulets and nuggets. Shields of Apollo and golden doors. A gold scorpion and a gold monkey. The crazy glow of the wall-to-wall bling tampers with the starch in your knees and makes them wobbly.

Why 100 objects? Because, he says, it’s like that thing Neil MacGregor did on the radio: A History of the World in 100 Objects.

Why the pretence? “I think it gives people different ways into the work. You know, it’s like when a guy comes out of the sea with a gold object, you just believe it. It’s built into us. We need to believe that if someone comes out of the sea with a gold object, it’s treasure. You can’t believe he just put it there.”

Surely no one will actually fall for this guff about Cif Amotan and his lost ship? “Of course some people will believe it. It’s like the Beatles and that Paul-McCartney-being-dead thing. Some people still believe it. Think about governments programming people’s minds and things like that. You think it would take a lot to make somebody believe something that’s not true. But it f****** doesn’t. I’ve worked on this for 10 years and I absolutely think Cif Amotan is a real person, because I’ve devoted so much time to him. It becomes real. And it becomes real quite quickly.”

For him, then, it’s all about belief. About how we can be made to believe things because we need to believe things. He’s not a political artist, but it’s certainly a warning about how vulnerable we are to institutional control — even if the institution in question is as seemingly innocent as a museum.

Interspersed among the specialist rooms devoted to gold, coins, armour, silver are the ridiculous ritual sculptures that Cif collected and that have been dragged out of the sea covered in coral and barnacles. Ho-ho. They’re huge and unmistakably Damien Hirst in their over-the-topness. A warrior woman riding on the shoulders of a bear is 23ft tall. She’s enacting a ceremonial conquest of a she-bear in an effort to appease the goddess Artemis. The one with the legs of a fly sticking grotesquely out of her back is Arachne, who was turned into a spider by Athena. And all these hilarious mythological absurdities have been made using the lost wax process whose principles have remained unchanged for 5,000 years. (Note to self: don’t get Hirst started on the wonders of bronze and the lost wax process. Because he’ll still be going on about it a year later.)

I like this one, Damien. It’s the fractured head of an ancient Egyptian goddess carved from gorgeous red marble. Look, she’s got a sacred inscription on her chest of a winged female deity. Isn’t that Aten, the solar entity whom the Egyptians called the life-giver? No. It’s actually Rihanna, carved from a life mould he made. And that’s not a sacred inscription. That’s her tattoo.

Thus the modern world keeps making naughty and spiky appearances in Cif’s ancient collection. Over at the Palazzo Grassi, there’s a sculpture covered thickly in barnacles that preserves the blurry outline of, er, Walt Disney’s Goofy. And this one here, entitled The Collector with Friend, isn’t that Walt himself holding the hand of Mickey Mouse?

“With the Disney characters, I just thought I would add something totally impossible. Because of the dangerous way I was trying to trick people, I thought, if I put that in, it’s not a trick. Then I started thinking about Disney. About Cif and his collection. About me, and what I was trying to do. And I figured it was all the same thing. And it all seemed to make sense. To have a person creating a whole world for themselves and for other people — that’s what Cif did. That’s what all artists do. That’s what I was trying to do. And it’s what Walt Disney did.”

He encourages me to take a closer look at the chap holding the hand of Mickey Mouse. The blunt Yorkshire nose. The protruding tummy. That’s Damien all right.

Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable is in Venice until Dec 3