For evidence of how history progresses in thunderous waves, you can do no better than visit the Royal Academy’s superb Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32, a centenary tribute. But wait. I do not mean the story of the revolution itself, and its destructive course. I was thinking of the actual show. Its attitude. Its journey. Its contents.

Ten years ago, this exhibition would have been unlikely. Twenty years ago, it would have been impossible. Not because the subject itself was a no-go. It wasn’t. On my watch as an art critic, I have seen scores of tributes to the art of the Russian Revolution. It’s a popular topic, especially for those unreconstructed modernists who view the futuristic achievements of Malevich, El Lissitzky and Stepanova as the high spot of progressive art in the 20th century. Confession: I am one of those. For sheer aesthetic excitement, I don’t think you can trump the modernist art of the Russian Revolution.

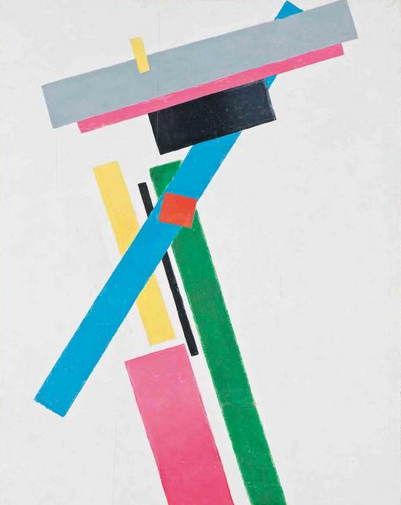

It was as if someone who’d been on the Stoli had taken a chainsaw to ornament and detail. Nothing in pre-revolutionary Russian aesthetics prepares us for the startling simplicity of Malevich and co. Nothing in the grim Stalinist era that followed is the result of it. It came from nowhere. It went nowhere. And this contrast with what came before and after gave Russian revolutionary art its get-out-of-jail card: it might have been Bolshevik and hardcore, but it felt like a liberation.

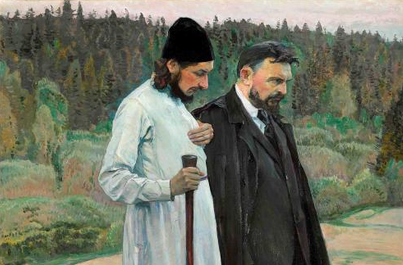

Previous exhibitions on the subject have, therefore, confined themselves to the exciting visual experiments of the suprematists and the constructivists. But not this one. This one dispenses brusquely with the notion that some Bolshevik art was on the side of the angels, and other Bolshevik art was not, by determinedly blurring the divide between the two. Indeed, the show begins by ignoring the good guys completely and devoting its opening rooms to fawning portrayals of Lenin and Stalin in the style that came to be called social realism.

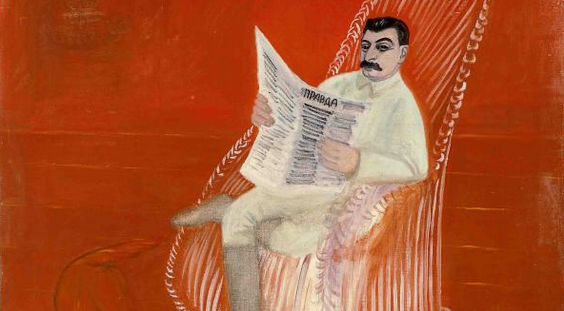

Isaak Brodsky pictures Lenin at work on his state papers, hunched unglamorously over a coffee table in what looks like the waiting room of an impoverished dentist. Stalin, meanwhile, black-haired and youthfully moustached, stands up from his desk, sticks out his chest and prepares to achieve something. The doer v the thinker. On another wall, Lenin, after his death, lies in state in a bright red coffin and exudes a divine peacefulness of the kind more commonly encountered in Buddhist deities.

So we are dealing with determined visual propaganda, with art aimed at the imaginations of the masses. In previous celebrations of the art of the Russian Revolution, this kind of imagery would have taken a back seat. Here, it takes the front seat. That’s what I mean about the thunderous waves. From the off, the current display appears hellbent on challenging the modernist myth of the revolution. Twenty years ago, no one would have dared present this argument.

If the show needed to distort the facts to make its point, it would merely be a typical 2017 event: a post-truth exhibition. But the opposite happens. The journey ahead argues convincingly and busily that the art of the suprematists and the constructivists needs to be understood as a part of the bigger picture, and not an exception to it. Social realism wasn’t only an alternative aesthetic imposed brutally by Stalin: it was also a parallel journey that shared its years with progressiveness. Indeed, the difference between the two approaches has been overstated.

The arguments for this are mounted on a journey that darts from paintings to pots, from photographs to textiles, from films to posters, as it tries to convey the extraordinary fecundity of Russian art in the years 1917-32. At every step, there is discovery. Previous investigations of the era would have ignored the factory interiors painted by Alexander Deineka in 1927 because they appear, at first glance, to exemplify “commie bullshit”. But a closer look at Deineka’s women at work reveals an ethereal second identity. Barefoot and pale, his factory girls float through their labours like a ghostly workforce kidnapped from the art of Piero della Francesca. Not quite surrealism, not quite modernism, Deineka’s curious paintings prove that to be a Russian revolutionary, you didn’t need to reach for a ruler.

It’s a point the event keeps making. The traditionalists were more revolutionary than we suspect, and the revolutionaries were more traditional. Some of the best things here are the fine wares produced by the State Porcelain Factory in St Petersburg. Using up old porcelain stock that had previously been covered in ornate tsarist cartouches and views of the Winter Palace, an impressive array of mainly female artists produced pots that go off the scale on the invention front. Natalia Danko gives us an elegant contrapposto figurine of a Woman Worker Making a Speech. Vasily Timorev decorates his plate with carefully observed identity papers. Posh porcelain at the service of the people.

And the range of arts explored here — film, photography, theatre, ballet, poetry, architecture, interior design — is as prescient as it is impressive. It’s not just Grayson Perry and his story pots that are being prefigured. Huge stretches of our own contemporary art, as it skips between boundaries and invades adjacent territories, are being set an example.

Arranging the resulting clutter into a coherent exhibition has tested the mettle of the unfortunates charged with fitting this inherently chaotic event into a suite of galleries created in the un-Bolshevik spirit of Sir Joshua Reynolds. They try hard to mask the inappropriate grandeur of the location with faux-Bolshevik partitions, Petrograd-style industrial trellising and unlikely Eisenstein cinemas in the sky: here and there, they succeed.

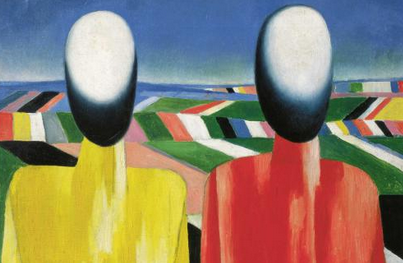

My high spot is the room devoted to Kazimir Malevich, in which a full-size recreation has been mounted of a show he had in Leningrad in 1932. High up on the wall, a black square and a red square confirm his faith in what he called “the zero of form”. Below is a triptych of gorgeous suprematist abstractions in which coloured triangles and cosmic circles soar like soap bubbles in floaty white space. Filling the room on either side is a marvellous selection of those curious peasant paintings in which he blurred the divide between the abstract and the figurative as he sought to convince the Stalinists of his plebeian ambitions. All has been redone perfectly, with original works.

It’s the summit of an event that manages, against the odds, to present an entirely fresh opinion of the artistic achievements of the revolution. Relentlessly interesting, packed with wows, keenly revisionist, this is exhibition-making of uncommon efficacy.

At the National Gallery, there’s also a rare arrival. I do not recall a show devoted to Guido Cagnacci. His dates, 1601-63, make him a close contemporary of Rembrandt and Velazquez. In his lifetime, his reputation was a match for theirs. But somewhere along the way, it fell between the cracks.

Considering what the National Gallery has unveiled for us now, his disappearance is a genuine surprise. Painted in 1660-63, his Repentant Magdalene is an extraordinary picture. Huge, complex, inventive, different, it shows a near-naked Magdalene sprawled on the ground, surrounded by gold and pearls. She has seen the error of her ways and is renouncing all her former riches, including her posh clothes. Behind her, a pair of allegorical figures act out the victory of Virtue over Vice.

What it is really about, however, is the seductive beauty of the near-naked Magdalene. This is what Cagnacci was infamous for: painting desirable blondes pretending to be Cleopatras and Magdalenes.

Having recently completed a film about the portrayal of Mary Magdalene in art, I can vouch for the fact that she was a regular loser of her clothes. I am also happy to concur with the view that Cagnacci was unusual in the amount of pleasure he gained from the loss.

Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32, Royal Academy, London W1, until Apr 17; Cagnacci, National Gallery, London W1, until May 21