A book thumped onto the mat last week. Published by Phaidon and the size of a thick paving stone, it was called Modern Art in America 1908-68. “Great,” I enthused, as I began flicking through its 350 full-colour pages. Just what I need to prepare myself for the Royal Academy’s America After the Fall, an examination of American painting of the 1930s. But it wasn’t. Almost none of the artists in the exhibition is present in the book.

Their omission is explained by differing attitudes to the word “modern”. The Phaidon book is a clueless document that parrots the view that the creation of modern art in America involved the production of local versions of various imported European isms, with abstraction at their helm. It’s a New York viewpoint, a MoMA viewpoint, and in most of its conclusions it is uninsightful, derivative, prejudiced or plain wrong.

America After the Fall, on the other hand, is about as insightful as an exhibition can be. Full of unfamiliar work by artists who will be new to British audiences, it presents a parallel story of American art that is not only riveting in itself, but also shines a helpful light on events in the United States today. The “modern art” to which this display is devoted is no less modern than the work with which the Phaidon paving stone is stuffed. But its drives are endemic and particular. So, therefore, are its truths.

The focus is on the art produced in America during the Great Depression — “the deepest and longest-lasting economic downturn in the history of the western industrialised world” — and the impact this seismic event had on the American mindset: the aesthetic attitudes it triggered or confirmed. As the show’s title implies, it was a historical moment with a biblical underscoring. God’s chosen people had brought disaster down on themselves. The Wall Street Crash of 1929 wasn’t just a financial failing. It had the atmosphere of a plague, a punishment, a divine comeuppance. And away from the concocted story of modern art, a gang of painters who have largely been redacted from the official version of American progressiveness produced a fascinating range of reactions to these critical episodes. That’s the story of the show.

We begin with an amuse-bouche that’s keen to evoke the prelapsarian spirit of American painting. By fiddling a bit with the dates, the RA has assembled a set of pictures that convey the optimism that preceded the expulsion from paradise. Thus, Charles Green Shaw paints a giant packet of Wrigley’s Spearmint Chewing Gum floating in front of the New York skyline. The simple rectangle of the gum rhymes with the simple rectangles of the skyscrapers, and the two together feel as if they are saying something sexy about modernity. Painted in 1937, Shaw’s gum’n’skyscraper combo is remarkably prescient in its prefiguration of pop art.

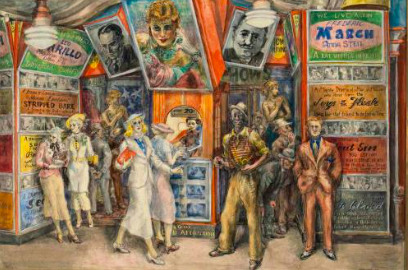

That’s the good news. The rest of the show is dominated by the bad news. Panning down from the skyscrapers, Reginald Marsh, a kind of 1930s Rowlandson, gives us hordes of excited out-of-towners pouring out of the subway like rats, or loitering like vultures outside a cinema where a Mae West movie is playing, and where their lecherous hopes find an echo in the snatches of typography on surrounding posters: “Joys of the flesh”; “Stripped bare”; “Dangerous curves”.

For previous generations, the city had been something wondrous and soaring: a victory over the skies. For the postlapsarians of America After the Fall, it has turned into Hades. Philip Evergood’s Dance Marathon, from 1934, shows a heap of collapsing couples trying to stay upright as they dance themselves beyond the limits of endurance for a few hellish bucks. “A sort of Last Judgment for the New Deal era” is how the catalogue describes it. The suspicion has taken root that modern America has sinned its way to the Great Depression: that New York was Sodom and Chicago was Gomorrah. And when Edward Hopper arrives in the show, with his lonely cinema ushers and forlorn petrol-pump attendants, the city becomes the setting for a hope-crushing ennui: somewhere the twilight never lifts.

All this is fabulous storytelling by a group of artists who had invented a brand of American realism that was deliberately avoiding the Esperanto of modernism. In the show’s next and best section — a central gallery devoted to rural America — the lament becomes more complex as we encounter a gang of painters whom 20th-century art criticism has generally rubbished as Regionalists.

Initially, their message is a comforting one. Charles Sheeler’s Home, Sweet Home is a lovingly recorded Shaker interior, with plain chairs and geometric carpets bathed in a pale national light. Homestead America is being presented as an alternative to the city: a native American paradigm.

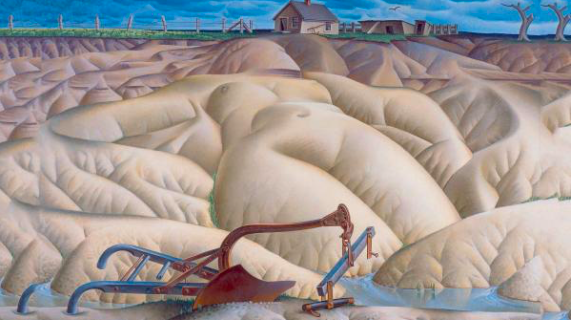

Plagues, however, come in clusters, and in the rural Midwest, the Great Depression was accompanied by the ecological disaster known as the Dust Bowl. Caused by greedy farming practices that involved ploughing up the fragile surface of the Great Plains, the Dust Bowl turned them into a windswept desert, strewn with animal skeletons and discarded ploughs.

All the way through this show, you can hear biblical notes being struck. But they are loudest in the Dust Bowl stretches. Alexandre Hogue, an artist I have never previously encountered, gives us an extraordinary image of erosion in which the top layer of a field has been blown away, revealing the corpse of Mother Earth lying supine in the ground. In the foreground, a biblical plough looms up in accusation, like the skeleton of a dead steer.

The most famous Regionalist painting is Grant Wood’s American Gothic, that familiar double portrait of two lean and pointy homesteaders standing bolt upright in front of their lean and pointed rural home. From the moment it was unveiled at the Chicago Art Institute in 1930, American Gothic has felt as if it stood for the spirit of America. Or at least for a version of that spirit.

You might have noticed that from the start of this piece I have been tempted to detour into contemporary America. With American Gothic, that temptation becomes irresistible. What Wood captured in his famous human rhyme seems so obviously to sum up the typical red-state voter: white, God-fearing, driven by a sense of entitlement. These glum Midwesterners may be chicken-thin and worn as gateposts, but they are God’s chosen people, standing guard over his world. The pointy home behind them may not actually be a church, but it sure as hell feels like one.

But — and it’s a big but — is this realism or is it sarcasm? As a secret homosexual and an artist renowned in private for his wit, Wood produced paintings that are devilishly difficult to read. Are we supposed to see the stern couple in American Gothic as guardians of the American way of life? Or are they being sent up? Is the old man a Leonidas who will defend his land to the end? Or is he a deluded old crock who cannot tell the difference between a trident and a pitchfork? For what it’s worth, I’m inclined towards the second reading. Hallelujah.

The show’s final room is its darkest. Set in the late 1930s, it records the growth of fascism in Europe and the effect it had on the faraway American psyche. Separated by an ocean from the realities of Franco and Mussolini, the American artists assembled here allow their imaginations to run riot as they intuit the arrival of the worst plague of all — war.

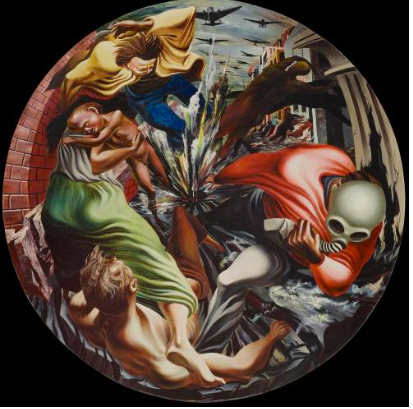

Peter Blume’s The Eternal City is a monstrous view of 1930s Rome, reimagined in the style of Hieronymus Bosch. That grotesque green jack-in-the-box popping out on the right — that’s Mussolini. In the show’s most brilliantly surprising moment, Philip Guston — yes, Philip Guston— describes the bombing of Guernica in a round painting filled with mutilated figures that feels like a grenade going off in a rubbish bin. After all the Warhol shows, all the repetitive American art histories, what a relief to encounter something so unfamiliar and so telling.

America After the Fall, Royal Academy, London W1, until June 4