Retrospectives can be mournful things. Their task is to look back at an artistic career and summarise it, which makes the retrospective the brother in arms of the obituary. “Where next?” they sometimes whisper at their end. “How much further to go?”

Fortunately for David Hockney, he is an artist whose work is characterised by its brightness, its sense of jaunty exploration, so the huge look-back at his 60 years in art that has opened at Tate Britain never grows bleak on us. From beginning to end, it remains chatty and cheerful. Indeed, so chatty and cheerful is it that this, too, becomes an issue. It’s like going to Stratford-upon-Avon and finding only the comedies. No Lear, no Hamlet.

The opening room baffled me when I entered. Stylistically, it jumps about all over the place, as work from all periods of his career is jumbled up. Swinging London stuff from the 1960s. Poolside pleasure-seeking in LA in the 1970s. An image from 2014 that shows people walking round a room whose walls are hung with pictures of people walking round a room. Whoa, David, slow down, screamed my aesthetic satnav. You’re losing me. The 1960s pictures were done with oil paints; the 1970s ones, acrylics. The 2014 one was a “photographic drawing printed on paper”.

A bit of careful looking soon explained the leaps. Hockney is deliberately making like Picasso, shifting from style to style, because there is no rule in art that insists otherwise. Who says an artist has to follow one path to the summit? Why not follow lots of paths? The question appears less urgent today because we live in multivalent aesthetic times, but back in the 1960s, when Hockney started, the modernist mindset that policed British aesthetics deemed the changing of styles to be flighty and unserious. Hockney, a shouty naysayer by instinct, on every topic from sexual liberty to smoking, is using this retrospective to make a point about artistic freedom.

But that is not all that is happening. The other big point being made in the jumpy opening room is that painting is ultimately about mark-making. It is not about realism. It is not about expression. It is not about emotion. It can have those things in it, yes, but what really counts is the way the painter conveys the information: the marks. If we understand this, we understand all that follows in the jumpy, multivalent, cheerful, rebellious and ultimately irritating journey ahead.

This is the biggest such retrospective in Tate history. Thirteen rooms. Much has been made of the little-seen works that are included. The first batch of these come from Hockney’s art-school days, when he experimented with abstract expressionism. White, wild and scruffy, the art-school abstracts from 1960 feature an artist who paints chiefly with instinct. I like their messy wildness because it makes Hockney’s talent as an intuitive mark-maker immediately obvious.

According to the catalogue, he is already dealing here with his covert homosexuality. Love Painting, from 1960, contains phallic shapes, I read, and a sense of the illicit. By 1961, the flirtation with abstract expressionism has passed — the first skip — and given way to a pop primitivism in which the painter’s crush on Cliff Richard is acted out by a pair of love-hungry blobs going at it like the clappers in a painting called We Two Boys Together Clinging. It’s a notorious work, and a cheeky one, its secret meaning encoded in a number symbolism learnt, apparently, from Walt Whitman. Thus, the numbers 4.2 written below the entwined blobs stand for the fourth and second letters of the alphabet. Hockney is dreaming of getting himself a crying, talking, sleeping, walking, living Doll Boy.

We Two Boys was painted when homosexuality was still illegal in Britain. The coded love pictures that follow are both brave and stubborn in a Yorkshire way. They offer constant evidence of a fascination with marks and signs. Whether it be the naughty inclusion of the number 69 or the snatches of graffiti found in the toilets in Earls Court or the tubes of Colgate toothpaste as stand-ins for phalluses, the blobby paeans to gay love are packed with secret messages.

The 1960s were Hockney’s golden years. Switching styles with Picasso-esque insouciance, he goes from being a wild abstract expressionist at the start of the decade to a precise classicist at the end. It’s difficult to imagine a wider pictorial canyon than the one that separates the thick smears of oil paint used to produce the clinging doll boys from the smooth acrylic perfection of the celebrated double portrait of Mr and Mrs Ossie Clark. Where the first picture is all sperm, the second is all eye: an extra-clear depiction of two cool presences in a cool room, whose cool space coolly updates the cool Renaissance language of Piero della Francesca.

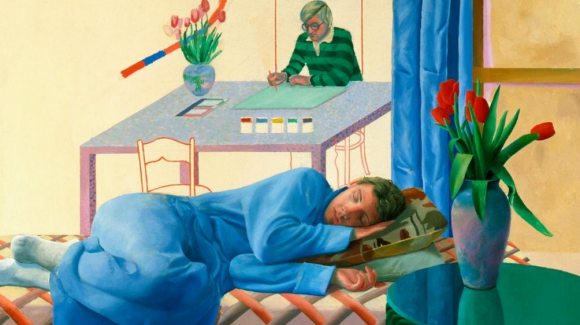

The display copes with his leaps by giving them independent rooms. Thus, Mr and Mrs Clark find themselves in a spectacular gallery filled with big portraits from the late 1960s and early 1970s, in which Hockney’s friends and collectors are examined in detail, in pairs, in perfect lighting, like luxurious double-page spreads in a lifestyle magazine.

The poolside pictures, with A Bigger Splash at their centre, get another space. The careful context makes it easier to see that their chief concern is, again, mark-making. Yes, the bright blue skies, the palm trees, the white-bottomed boys discovered on Hockney’s first visit to California in 1964 set an indolent mood for the pool pictures, but the aesthetic battle being conducted here is deceptively fierce: the battle to paint water. What are the marks that best convey the sparkle of the Californian sun in a rippling pool? How can you paint something as brief and intangible as a bigger splash?

So far, the spirit of investigation that drives this show has been successfully tracked. Personally, I will go to my grave unenamoured of the bright plastic dryness of acrylic paints, Hockney’s preferred method in California, but I do not doubt the view that they are an appropriate medium for capturing the sunny flatness of Los Angeles, where the poolsides, the showers, the cacti all look as if they have been acquired from the same department-store range.

Also pleasing are the experiments with photography that commence in 1982. Having been warned that Picasso is always a predecessor for Hockney, it is easier to recognise the busy Polaroid collages of landscapes and friends as inventive efforts at a photographic cubism that aims to see things from many sides at once. The photography holds up well. It’s what comes next that begins to disappoint.

A room entitled Experiences of Space continues the search for cubist viewpoints in huge and wobbly 1980s interiors that feel like painted quilts for a kid’s bedroom. This relentless jauntiness continues in panoramic views of the Grand Canyon, in which the felt-tip colours of Hockney’s poster years turn the sublime vistas into cartoonish racetracks Dick Dastardly might enjoy. Depth and emotion have been replaced by a cheerfulness you can stick to the fridge.

Where the first half of the show is laced with successful invention, the second becomes fidgety with it. A sense emerges that Hockney is constantly changing styles, like a man in a midlife crisis who keeps buying new cars. Going back to Yorkshire in 2004 triggers a welcome return to muted shades and cloudy moods, as the British weather restores the sense of poetry that California dried out. But it’s a brief respite. By the end of the 13 rooms, he’s back in LA trying out a bewildering array of gadgets and methods.

Ironically, one of the artists reworked on computers in the final stretch is Cézanne, the archetypal pictorial grumblebum, who never deviated from his chosen path. A set of poker lovers, hunched round a table, pay homage to Cézanne’s Card Players with assorted photographic gimmicks that seem to get in each other’s way.

Stop experimenting, David, I found myself wishing, in a final room that buzzed and bleeped with electronic markings produced on iPads. Just tell us something deep again.

David Hockney, Tate Britain, London SW1, until May 29