Dear Maria and Tristram. Hee-hee. Sorry. It’s just that whenever I see the name Tristram, I think of my erstwhile colleague on these pages, the great television critic AA Gill, who used “Tristram” as a shorthand for all the privileged, Cambridge-educated types who work for the BBC. You, of course, are Cambridge-educated, the son of Baron Hunt of Chesterton, and you’ve worked for the BBC. But in your case, it’s just a coincidence, I’m sure. Apologies, again, for the giggle.

What I really want to do here is to congratulate you both on your new jobs. The positions you are about to occupy are two of the great public offices of art. Few get to rise to them. Fewer still are any good at them. So I know you will not mind me proffering some advice on what needs doing and how to do it.

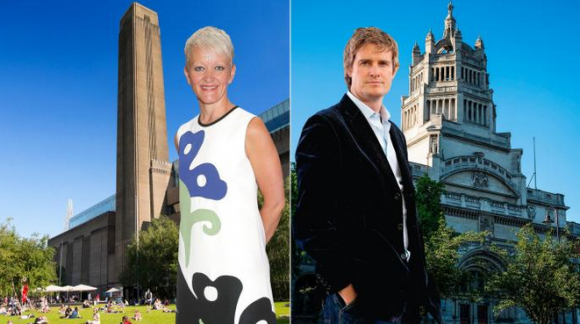

I’m going to start with you, Maria, because I know you better, and because taking over from Nick Serota as the Obergruppenführer of the Tate empire is the bigger job. Indeed, so big is it that some will be surprised if you don’t fail at it. Not me. I reckon you’re the kind of person who can succeed at anything you set your mind to.

Do you remember that time when I came to your fiefdom in Manchester, and you showed me round the Whitworth Art Gallery, where you were director, and which you had completely transformed? That was the year in which the Whitworth won Museum of the Year, an accolade it fully deserved. I actually studied art history at Manchester, and remember the old Whitworth well. How gloomy, bricky, hessian-lined and poky it was.

You, however, in your 10-year stint as director, opened it out and filled it with light. You turned it into somewhere that put on inventive exhibitions and attracted the public. You raised money for it. You changed it. And in doing all that, you changed Manchester, because for too long this great northern powerhouse had been culturally stagnant. Before you came along, all people up there ever seemed to want to talk about was LS bloody Lowry.

That said, your new job as director of all the bits of the Tate empire, the whole shebang, will test every atom of your talent. In his almost 30 years at the helm, Serota turned the Tate into a mega-institution of unprecedented power and reach. As the creator of Tate Modern, he was the creator of the most popular modern art museum in the world. Six million people a year turn up there to climb the stairs and wander around the foyers.

My own view is that, under Serota, Tate grew too big. Since the £260m extension was added, Tate Modern itself feels gargantuan. It’s as if the dimensions of an international airport had been visited on the intimate and whispery world of art. All those empty foyers and vestibules and lifts. Getting close to the art is hard. What it really needs — and I’ll risk saying this even though it may get me into cultural trouble — is a woman’s touch. By that I mean it needs to become less about size and more about meaning; less phallic and more welcoming; less cool and more honest.

One thing worries me about you, Maria — that you studied critical theory for your MA, not the history of art. It worries me because there is a tendency in art today to seek to understand it by reading about it, rather than by looking at it. The mountains of ornate theory you would have had to wade through to achieve your degree appeal to a certain kind of curatorial mind, but we both know that it’s not the way artists or gallery visitors actually think. You’re from Birmingham. You changed Manchester. In your heart of hearts, you know the London art world exists in a bubble, and that this bubble is disconnected from the heartlands of Britain.

I’m not talking Brexit here. I’m talking emotion. I’m talking about the power of art to move people, transform them, delight them. Under your predecessor, the Tate empire grew too large and too cold. Instead of celebrating quirky British talents such as Grayson Perry, Tracey Emin or Sarah Lucas, it seemed to be embarrassed by them and to prefer the imagined “rigour” of their international counterparts.

People have been saying your predecessor will be an impossible act to follow. When it comes to politicking, diplomacy, schmoozing rich people and keeping in with prime ministers, he was, indeed, masterful. But one thing you have, which he usually hid, is heart. And right now, as fate would have it, heart is exactly what the Tate empire needs.

Tristram, I don’t know you, except for the things of yours I’ve seen on the telly. You were OK in those, if a tad posh. I have no idea what sort of MP you were up there in Stoke-on-Trent, but I have no problem with you crossing over now into the world of museum directing. If I were a Labour MP, I, too, would be jumping ship.

As for that infamous appearance of yours on Question Time, where you clashed with the grandiloquent Cristina Odone on the question of whether nuns make good teachers, let me just say I support you totally on that. I was brought up by nuns and priests. They treated me like a fat little sinner who needed weekly whipping, and succeeded only in turning me into an atheist.

However, one thing Odone said during your Question Time clash is pertinent, because she made the point that you do not need to have been to teacher-training college to be a good teacher. By the same token, you do not need to have worked in a museum to become a good museum director. In fact, not having worked in a museum may even be an advantage.

What you, as a trained historian, have instead is an instinctive fondness for the past that not all V&A directors have recently exhibited. Your predecessor was notably lacking in a taste for days of yore. Like many museum directors today, he seemed more interested in media attention and cultural impact than in the stewardship of his institution’s fabulous historic holdings. Occasionally, he didn’t even turn up at exhibition openings, so busy was he having a cultural and media impact. As a result of all this international rubbernecking, the scholarship for which the V&A is globally renowned gathered moss and declined.

Tristram, talk to your curators. Not just to the ones who put on the David Bowie show or the displays of Alexander McQueen. They’re doing fine. Talk to the ones who run the Islamic department or the Japanese section; the India scholars and the porcelain experts. These are the people, with their unparalleled knowledge of the world’s cultural past, who have been sidelined and neglected. Let’s face it, putting on Bowie shows is easy. Teaching us about the aesthetic meanderings of Japanese art in the Meiji period is not.

This year also sees the opening of the grand new V&A entrance on Exhibition Road, with its splendid galleries. So I’m hoping you will seize the opportunity as well to open the doors again to the proper scholarship for which your museum is so rightly appreciated.

Tristram and Maria, break a leg. And welcome.