The Fourth Plinth project, on Trafalgar Square, has been a success for various reasons. The first is its location. I mean, come on, Trafalgar Square! Nelson’s Column behind, the National Gallery in front, kings and generals all round. The lions. The view down to Big Ben. You could not find a more potent location for a contemporary sculpture than Trafalgar Square.

The second reason is the frisson caused by placing something so conspicuously contemporary in such a determinedly traditional setting. What delightful madness it is to have a giant blue cock sharing a heroic platform with Major General Sir Henry Havelock. The modern world is blowing raspberries at the past. On Trafalgar Square, at Fourth Plinth time, the spirit of Hogarth lives on.

The third reason is the choices made. By and large, they have been good ones. In the beginning, they were actively brilliant. Marc Quinn’s giant marble statue of the dysmelic Alison Lapper, rhyming her physical shortenings with the Venus de Milo, must be ranked as one of the most significant sculptural moments in Britain’s postwar art history. What a huge blow was struck for issues of disability by Quinn’s moment of sculptural genius. Not far behind was Mark Wallinger’s Ecce Homo, that pathetic human Christ who tiptoed to the edge of his plinth like a timid Olympic diver who has lost his nerve. What excellent contrasts Wallinger drew between the heroic and the humble.

More recent efforts have been patchier. The current one, by David Shrigley, a giant thumb poking into the sky, feels passively aggressive: a thumbs-up with the mood of a V-sign. I liked it when it was unveiled, but will now be happy when it is gone. It brings something graceless to the square, the shallow jokiness of afternoon TV.

It was with bounding enthusiasm, therefore, that I three-stepped it down into the National Gallery’s basement, where the latest batch of proposals for the Fourth Plinth projects of the future have been unveiled. Five proposals are presented, with maquettes and short explanatory notices. Two of these will get the go-ahead.

The most immediately arresting is a wobbly tower by Damian Ortega, constructed from a VW camper van with scaffolding on top of it, then some oil drums, then a ladder. Called High Way, the wobbly totem pole forms a homemade stairway to heaven. Climb it if you dare, hippie. It’s fun. But I suspect the joke would quickly wear thin.

Huma Bhabha’s blobby sci-fi humanoid with black legs and a white head can be immediately dismissed. It’s ghastly. And the evening-class aesthetics of the Raqs Media Collective, who give us a statue of George V as emperor of India from which the king himself has been removed, leaving only his cloak of office, is a dreary art gesture from page one of the postcolonial sociology manual. They even have the lack of invention to call it The Emperor’s Old Clothes.

The weirdest proposal is Heather Phillipson’s giant blob of cream with a cherry sticking out of it. Licking the cream is a huge fly. Licking the cherry is a whirling drone, which is actually relaying live pictures of those looking at it onto a nearby TV screen. God knows what it’s about. But it would certainly bring something new to the plinth, and you probably need to stare at it for a year to make sense of it.

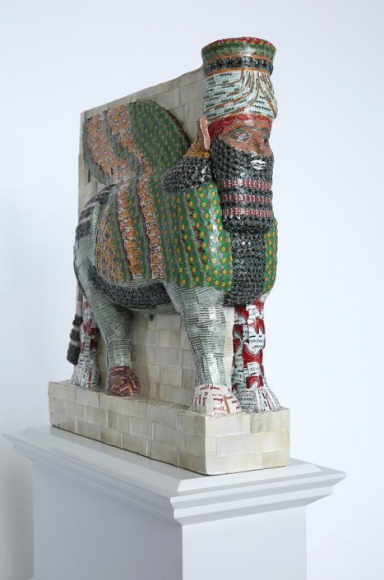

Best of all is Michael Rakowitz’s winged bull in the Assyrian style. At first sight, it looks like a slab of ancient art that has lost its way and blundered into a contemporary art situation: something that has escaped from the British Museum, perhaps? High above the plinth it looms, a stern hieratic figure with the body of a bull, the wings of an angel and the head of a king, all decorated in the trademark Assyrian colours of green and orange.

It’s actually a recreation of the lamassu, a protective deity that stood at the entrance gate of Nineveh from 700BC, but was destroyed by Isis in 2015. Lost in Iraq, it has been remade here out of empty date-syrup cans, a poignant reminder of the once thriving industry crushed by events in the Middle East. Extraordinary to look at, deep and deceptive in its meanings, different from anything seen here before, scarily relevant and heartbreakingly sad, this is the proposal to go for.

At Annely Juda Fine Art, the celebrated public sculptor Richard Wilson has gone unpublic on us with the first show of his in a private gallery that I remember seeing. Has he had one before?

Wilson is publicly celebrated because he has created a handful of important works that defined a moment. His 20:50, a room seemingly filled with black sump oil that reflected its surroundings as crisply as an obsidian mirror, was a signature sculpture of the 1980s and remains one of the most popular exhibits at the Saatchi Gallery. In 2008 — the year Liverpool was our European Capital of Culture — he cut a giant circle out of the side of a Merseyside office block and used heavy engineering to make it spin impossibly round and round.

Thus, Wilson brings something unique to British sculpture. His calculations are as precise as a Nobel prize-winning scientist’s; his thinking is as wacky as the fancies of an opium smoker. The result is a mad and marvellous art that explores a divide few of us even knew existed: the divide between surrealism and minimalism. As I said. Unique.

That said, his efforts to do this indoors at Annely Juda are only intermittently successful. The biggest works here are mysterious wooden constructions, giant Rubik’s Cubes gone wrong, which actually mimic the dimensions of spaces found just outside the gallery — the corridor at the top of the stairs, the facade on the street. These real-life spaces have been exactly measured and mapped, then turned into their wooden equivalents with clever sculptural origami. A set of drawings accompanying every sculpture makes things clear.

It’s ingenious stuff. But it never quite turns into poetry. So big are the wooden doppelgangers that they fit awkwardly into these modest spaces and — I hate to say this — cry out for a big white cube in which to present themselves more coherently. The DIY feel of their plywood and MDF construction interrupts their solemn minimalism with B&Q notes, like scratches on vinyl.

The smaller works are more successful. Blocka Flats is a cupboard-sized sculpture made by sawing a small cabinet into slices, then reassembling them at a jaunty tilt that appears somehow to enlarge every dimension. The drawings explaining this and the bigger constructions are a beautiful mix of precision and mystery.

Best of all is a room full of maquettes for some of Wilson’s best-known works, in which his signature sculptures are presented to us in doll’s-house form. The tiny scale adds an unexpected note of play to the careful engineering. Brunel in Wonderland.

Fourth Plinth Shortlist, National Gallery, London WC2, until Mar 26; Richard Wilson: Stealing Space, Annely Juda, London W1, until Mar 25