Up on the Sistine Chapel ceiling in Rome there is a blonde looking at herself in a mirror. If you’re standing at the back of the chapel, she’s high up on the right, among the ancestors of Christ. A beautiful woman transfixed by her own reflection.

The blonde’s role in Michelangelo’s dense symbolism is to represent vanity. In art, women looking into mirrors have always represented vanity. That’s their artistic purpose. Vanity was seen as a dangerous human weakness. Something to be fretted over and regretted.

Fast-forward 500 years, and all that has changed. Today, not only does there seem to be a woman in every mirror, but the very concept of “vanity” seems to have taken a direct hit in the bows. For centuries, nay millennia, vanity was understood as something to be avoided. “For heaven’s sake, take your eyes off yourself,” was the message of Michelangelo’s Sistine blonde. Today, not only is it culturally acceptable to adore the sight of yourself, but the pursuit of our own presences has turned into an international epidemic.

Wherever we look, there we are. On Instagram, on Twitter, on Facebook. In every corner of the smedding cosmos, we, us, me, moi are staring back at us as we elbow ourselves into our neighbour’s sightlines like a bunch of mad shoppers at the Boxing Day sales. Today, nobody is a nobody anymore. Not on their Instagram account at least.

Perversely it was art itself, the same art that invented the woman in the mirror, that invented the selfie. If you go left from Michelangelo’s blonde in the Sistine Chapel, over to his Last Judgment on the far wall, you will see a fearful-looking naked chappie sitting on a cloud at the feet of Christ, holding what looks like an animal skin. The naked chappie is St Bartholomew, a celebrated Christian martyr who was skinned alive by the Romans. What he is actually holding is his own skin. And the face on it is Michelangelo’s. It’s a self-portrait. On the most important wall in the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo has inserted himself into the height of the action.

What’s interesting about Michelangelo’s Sistine selfie is that it is an early example of role-playing. This isn’t Michelangelo, the real bloke. This is Michelangelo pretending to be the skin of St Bartholomew. He’s acting out a part. And that’s the thing about selfies. From the start they were never about the real you. They were always about an imagined “you”. A construct. A projection.

It’s as true today of Kim Kardashian “curating” her own nudity on Instagram, or Cindy Sherman imagining herself to be Caravaggio, or the woman you sit next to in the office dressing up as Cindy Sherman imagining herself to be Caravaggio, as it was of Michelangelo “curating” his nudity in the Sistine Chapel. In the world of the selfie, no one is really them.

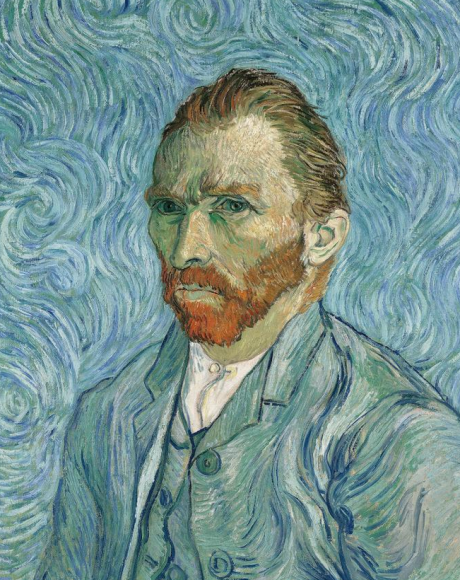

Artists were the first selfie-takers because they were the only creatives in the past who could actually do them. What is now easy used to be difficult. Before the advent of smartphones and mirror functions, only those who could paint and draw to a high standard were capable of preserving a convincing likeness. Not only did you need to stare into a mirror for hours, wrestling with your own reality, but you needed also to say something meaningful. Looking like you was never enough.

No wonder the great self-portraitists are such a miserable bunch. The greatest of them all, Rembrandt, is one of art’s glummest presences. Rembrandt painted about 50 self-portraits in all — Kardashian numbers! But in none of them does he appear to enjoy what he sees. Even in his earliest selfies, the young Rembrandt looks as if he is counting the days. By the time he gets to old age, his face is as lined with pits and wrinkles as a pensioner’s scrotum. Yet this, too, is role playing. Those funny hats he wears, the gold chains, the fur coats, are studio costumes put on for the picture. This was not the clobber he wore in the street. Rembrandt’s selfies are fantasies about the passage of time, the shortness of life.

The same with Caravaggio, who popped up regularly as Bacchus, the god of wine, with his toga slipping off his shoulder and a crown of vine leaves around his head. Caravaggio dressed up as Bacchus to make the same point that Rembrandt makes. Life is short. Enjoy it while you can. Because it will soon be over.

Among art’s keenest self-portraitists, not one of them, not Gauguin, not Van Gogh, not Frida Kahlo, can be described as an optimistic presence. Something about looking into a mirror, staring deep into yourself, turned the self-portraiture of the Old Masters into a dark and profound pursuit.

That is no longer true. Today, taking selfies is simples. Just point and click. Anyone can do it. Famous politicians gathered at important summits can do it. People falling out of aeroplanes can do it. Women in the bath can do it. Astronauts orbiting the moon can do it. We can all do it. The disappeared have disappeared. A Niagara Falls of selfies is cascading down on us from the heavens as every nobody on the planet is handed the tool with which to turn themselves into a somebody.

All this is the subject of an exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery that is heading our way. Combining Old Master examples with a selection of the best modern efforts, From Selfie to Self-Expression at the Saatchi will seek to understand why we humans cannot take our eyes off ourselves.

From Selfie to Self Expression at The Saatchi Gallery until 30th of May 2017