There is a buzz in the ether right now about abstract art. Lots of shows. Lots of rethinks. Why? The question is worth asking, not just for the light it throws on the past, but for the illumination it offers to the present. So we’ll come to that. But the first thing to say about Abstract Expressionism at the Royal Academy is that it is a stirring event: a big, grand, no-nonsense art show that lifts the spirits and pounds them.

The sheer purity of the experience presented here — the feeling that this is an exhibition about painting and sculpture, and that’s it — is so unusual these days that we may even term it “radical”. This marvellous selection, with its unpolluted artistic presence, its clear faith in the emotional impact of big pictures with big colours, feels like an escape from the tasting menus and a return to mamma’s food.

How many years is it since we had any kind of examination of abstract expressionism? I’ve been around a long time, but I don’t remember such a show.

I remember monographs at the Tate on Pollock, Newman and Rothko, but the movement as a whole has lain dormant in our understanding. The sense persists that it was a dinosaur among artistic tendencies — lumbering and unsophisticated, macho and American. And the fact that the CIA is known to have employed it in the propaganda campaigns of the Cold War has earned it so many black marks in the book of contemporary curation that only an institution as bare-chested as the Royal Academy might ever have thought it a good idea to tackle it now.

The show is a mix of themed stretches devoted to telling aspects of the movement, interspersed with one-room celebrations of the stars. Thus, Jackson Pollock gets the RA’s central galleries, the best rooms in the house, where a generous selection of his work culminates in a stare-off between two of his biggest pictures: Mural, painted for Peggy Guggenheim in 1943, and Blue Poles, from 1952. The latter is the ultimate drip painting, 16ft of splats, dribbles, crashes and feints, surging from left to right like a tidal wave that’s picked up some telegraph poles. Borrowed, ambitiously, from the National Gallery of Australia, in Canberra, it’s brighter than your average Pollock and a thrill to see.

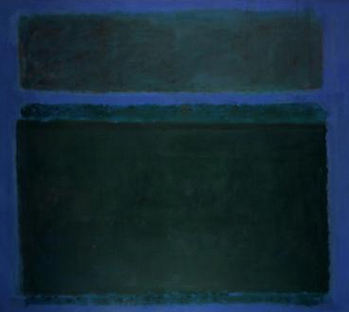

Rothko, whose oeuvre is full of achievement, but not, perhaps, of signature works, has been given the central rotunda, where a suite of his beautiful fogs takes us through a catalogue of his favourite colour combinations. Yellow and orange. Bright blue, dark blue. The mustardy green of a late summer lawn. Blacks and yellows that clash, salamander-style. It’s delightful, but perhaps a touch too varied. We get none of that sense of doomy theological purpose you feel among the purple Rothkos of Tate Modern.

Unexpectedly, the show starts with a selection of self-portraits. Who knew the ab exes did self-portraits? There’s Rothko again, in a private painting borrowed from his son, Christopher Rothko, standing bulkily before us in shades, from behind which he appears to be studying us as intently as we study him. And there’s Pollock while still a teenager — big eyes, big ears, big existentialism — staring sweatily out of the dark, in a picture so clunkily anxious that Rembrandt would have painted it more subtly with his foot. Pollock, Rothko, Arshile Gorky, Lee Krasner —none of these glum self-portraiteers is in it for the pleasure or the fame. This bunch are in it for the struggle, the weight, the meaning.

Also in the opening room is a selection of early works in which the giants-to-be evince their precocious determination to tackle subjects at the epicentre of the human condition. The ab exes didn’t sweat the small stuff. Pollock’s Male and Female, from 1942, is some sort of exploration of the interaction between the sexes. But who knows which of the swirling blobs represent the male components, and which the female? Or what the weird mathematical calculations scrawled across the picture like blackboard markings from an algebra class are supposed to add up to? All that is finally unmissable in this frantic painting is that the interaction between the sexes is a condition closer to war than to love.

Note again the date of Male and Female: 1942. These days, the ab exes get accused of machismo and melodrama, but, as the show’s co-curator, David Anfam, emphasises in the catalogue (great catalogue: worth getting), this is art rooted in an especially bleak stretch of 20th-century history. The Great Depression, the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, the invention of the atomic bomb — the compost in which the ab exes were planted was unremittingly black.

Having explained why the movement acquired its taste for existential themes, the show, to its credit, puts aside its bleak historical understanding and gets down to the real business at hand here, which is gathering up the best examples it can find and hanging them in exhibition circumstances that feel close to perfect. I’m not sure I have ever seen these galleries look better.

It’s something that works not only for the painters, but also for the show’s only significant sculptor, David Smith, whose inventive weldings sit in the centre of every room and seem to complete it, like a fountain in a courtyard. Made mainly out of discarded bits of agricultural machinery, Smith’s sculptures have banged and bent the rusty metals of the Great Depression into forms that are light on their toes and full of surprises. Ploughs have been sent to ballet classes.

Heavens, but there are some fabulous stretches to this event. In the de Kooning room, they have somehow managed to persuade American lenders to part with an explosive row of four of his “Women”, the celebrated expressionist nudes that are often accused of misogyny. That’s not how they strike you here. Yes, the paintwork is slashing and active, and everything is angular and carved up, yet the violent mood describes not the subjects themselves, but the tone of their creation. The presence of de Kooning is as tangible here as the presence of the “Women”. These are paintings about the ecstatic savagery of a sexual relationship.

In a show packed with spectacular stretches of paintwork, there is nothing finer than the three ravishing canvases by Arshile Gorky that decorate the end wall of the second room. Born in Armenia in 1904, Gorky was a living link between pioneering European modernism and these newfangled Americans. The influence of the surrealists, especially Miro, is immediately obvious in the acrobatic skips and skates of his paintwork. But for my money, he improves upon Miro by bringing bigger emotions to the table: a bigger sense of sadness; a brighter burst of joy.

On and on it goes. Superb stretch after superb stretch. Barnett Newman, the minimalist before his time, whose paintings strike you with their spectacular simplicity, is presented here as a seeker after sublime religious effects whose art looms over you like a clerestory window and bathes you in thin zips of celestial light. Size was an ab ex speciality. Clyfford Still, so notable, so rarely seen, has a thrilling room to himself, filled with pictures so mountainous that looking at them involves a form of climbing.

Commendably, the show refuses to get hung up on the differences between the “colour-field” ab exes, such as Rothko and Newman, and the flaying expressionists Pollock and de Kooning. Yes, the first bunch prefer stillness and the second go for frenzy, but, in the end, these differences are nothing more complicated than the choice of a horse for a course. Some emotions are slow and sublime. Others are quick and frantic. The bigger point being made here is that this is an art that set out to paint the way we feel, not through description, but through evocation and sensation.

So what important message does this marvellous and juicy past have for our brittle and embattled present? Oh, that’s simple. There’s not enough emotion in our art any more. We think too much and feel too little. That’s the message.

Abstract Expressionism, Royal Academy, London W1, until Jan 2