Modern art is so popular these days — with its record-breaking prices, its endless biennales, its art fairs, its art stars, its £260m Tate extension — that it’s easy to forget this was not always the case. Those of us who are longer in the tooth can remember the days when modern art in Britain was something to be avoided. In the old days, if you put up a sign outside a gallery saying “Modern art on show here”, the queues would snake in the opposite direction.

I’m remembering this now because an exhibition has opened at Tate Britain that, unfortunately, brings it all back. Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979 is drab, grey, dismal, pretentious, self-important, joyless and pitiful. It’s as tedious a display of art as I have seen since, well, 1964-1979.

Conceptual art has always been a problematic piece of art territory. Not just in Britain. Everywhere it arrived, it planted a kiss that was cold, dry and sexless. By privileging the responses you have between your ears, rather than before your eyes, it’s a genre that leaves the emotions untouched and appeals instead to the left cortex — the bit that works things out, calculates, deciphers and obsesses about language.

The reasons for its unpopularity become evident as soon as you step into this show. Actually, they are evident before you step in, because an extra-long vitrine packed with texts and blurry archive photos is waiting in the vestibule. What a lot of documentation. Sorry, but I came into art to see things, not to read them. When did enjoying art become confused with doing homework? Between 1964 and 1979, appears to be the answer.

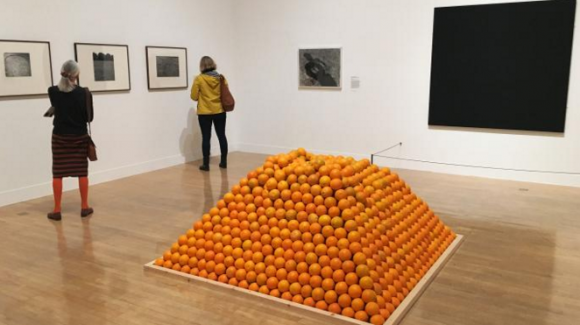

Beyond the vestibule, the opening gallery is the most pleasing in the show, for the simple reason that it has at its centre Roelof Louw’s Soul City (Pyramid of Oranges), from 1967. The pyramid of oranges is exactly that. In an early effort at visitor participation, you are encouraged to pick one from the pile and take it home. “By taking an orange, each person changes the molecular form of the stack of oranges,” Louw explained at the time, “and participates in ‘consuming’ its presence.”

This might have been true in the artist’s mind. But in the eyes of the visitor, the best thing about the oranges is that they are orange. The sudden drench of colour they supply cheers up your eyes like the glimpse of an oasis in a desert. In a room filled otherwise with typed-out texts and dull black-and-white photos, the burst of orange reminds you why the visual arts are a visual art.

The display ahead investigates an era when a bleak collection of artists working in Britain embarked on a collective misunderstanding of conceptual art. They did it for decent and perhaps even praiseworthy reasons. But it was a huge misunderstanding. Keith Arnatt addresses the key issue — tangentially, of course — in a photowork from 1968 called Invisible Hole Revealed by the Shadow of the Artist. Digging a hole in a lawn, Arnatt lined it with mirrors and placed a square of turf at the bottom, so the turf was reflected in the mirrors and the hole became invisible. Only when his shadow fell across it in an oddly disjointed fashion could you see it was there.

For Arnatt, the hole and its implications asked huge questions: “How visual does visual art have to be?” The point of his piece, I read, was to challenge those brash modernist sculptures of the 1960s that were determined to differ dramatically from their surroundings: determined to be seen. Here instead, Arnatt reasoned, was a piece of conceptual art that was determined not to be seen.

“So what?” you will be tempted to ask. “So nothing much” would be the honest answer. Faced with fey conundrums of this ilk, it is no wonder the British public walked away. Not only was Arnatt’s piece addressing its issues in a form nobody understood, the issues themselves were of little interest to the world at large. One corner of the art shed was having a moan at another corner of the art shed. In Harold Wilson’s Britain, the last thing on most people’s minds was the degree of difference that outdoor sculpture should adopt.

Absurdly, however, the main reason provided here for the rise of conceptual art was the desire to connect more closely with the outside. The show’s opening wall text suggests we should see the art gathered here as an attempt to turn away from “something rarefied and set apart from the world”, and to replace it with “something that acted within the world”. Had we been living on the planet Zog, that might have washed. But we weren’t.

In another of his pieces, Arnatt, who was obviously something of a narcissist, shows himself 11 times eating the 11 words “eleven portraits of the artist about to eat his own words”. But it’s precisely because he was such a narcissist, and looks like a moody baddie out of a spaghetti western, that the results have something about them. Not because the visuals are meaningless. But because they are not.

Richard Long, famous then as he is now for his extended traipses through the landscape, shows us the line traced in the grass by his feet: an absence that feels like a presence. Braco Dimitrijevic photographs a stranger in the street, then puts his photo on a bus that passes daily by the same encounter spot: an absence that feels like a presence. Bruce McLean reproduces a photograph of the Duke of Bedford’s lawn, on which two silhouettes have been mowed of the duke and his duchess: an absence that feels like a presence.

All this is watchable. Where the exhibition grows tortuous and a test of patience is with the arrival of the group known as Art & Language. Eschewing imagery altogether, this dour Marxist collective bombard us with word pieces about dialectical materialism and the impact of filing cabinets. Represented by no fewer than 26 works, they kill the show with their clunky Spartist witterings. Take the poetry out of concrete poetry and what are you left with? Concrete.

Perversely, although conceptual art traces its origins back to Marcel Duchamp and his famous call to place art “at the service of the mind”, Duchamp himself never forgot art’s visual duties. Even a work as conceptually hardcore as his urinal gives us something surreal to look at: it may not be beautiful, but it is arresting.

With Duchamp, there was also the humour. Whether he was drawing a moustache on the Mona Lisa or using a coffee grinder as a sex toy in his marvellously mysterious Large Glass, he rarely missed an opportunity to giggle like a naughty schoolboy. It brought a lightness of touch to his creations, and the sudden gusts of life that are usually missing from the dreary outpourings of his British disciples.

Conceptual Art in Britain 1964-1979, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Aug 29