The best thing achieved by the British Museum under the directorship of St Neil MacGregor was a connection to the modern world. Previous directors had allowed the ancient objects with which the BM is so spectacularly packed to acquire an air of decorative uselessness; to belong only to the past; to sit there looking old or powerful or pretty. MacGregor changed that.

In shape-shifting exhibitions such as the Persian blockbuster or the one devoted to Afghanistan, MacGregor used the past to explain the present, and even to influence it. The conflicts of the modern world became conflicts with a setting, a context, an explanation. It was an invaluable service. We can only hope that the new director, Dr Hartwig Fischer, from Dresden, continues it.

For now, we can still look forward to the shows that St Neil ordered before he left, and that bear his stamp. Sicily: Culture and Conquest is the first of these, and it is, in various ways, an archetypal MacGregor event — lucid, engrossing, delightful and, above all, relevant. This time, however, the relevance is lightly disguised.

Even the most ardent fan of modern Sicily would be hard pressed to make a case for the island’s continuing international import. It is not a territory with extensive modern tentacles — unless you are talking about the mafia, and a MacGregor show would never be that vulgar. Ancient Sicily, on the other hand, turns out to have been a beautiful and precious example of different cultures living and working together: allowing difference; showing tolerance; making great art. This, then, is a show about ancient Sicily whose message might be aimed at modern Europe.

MacGregor’s brilliant and sneaky contribution to the Brexit debate is a mix of helpful texts, evocative scene-settings and gorgeous objects. Beginning with the art of the prehistoric Sicilians, the show makes tangible the contributions of the various landlords who ruled the island from 10,000BC to the 15th century. Ancient Sicily was an especially desirable conquest. Fertile, beautiful, dramatic, it was home, also, to the biggest and most active volcano in Europe — Mount Etna. With hell bubbling constantly underfoot, the island must have felt like a divine gateway.

It is no accident that Homer’s Odyssey is so often set on Sicily’s fatal shore. It was here that the giant Cyclops threw his destructive boulders at Odysseus’s fleeing boat. And here, too, that Persephone, the Greek goddess of fertility, was abducted by Hades, ruler of the underworld, causing the earth to grow barren.

All this the show explains with an exemplary parade of fascinating objects. A tomb slab created by the first recognisable inhabitants of the island, around 2,000BC, makes the charged nature of Sicily’s atmosphere dramatically tangible. An abstracted penis with testicles is entering an abstracted uterus topped by some breasts. The entwined organs are a metre high. And the boldness with which they relate the coming of death to the creation of life is magnificent.

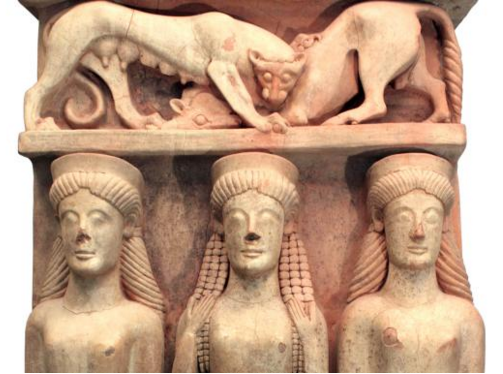

Persephone was popular in Sicily, celebrated in impressive sculptural altars and scores of charming terracotta figurines. She is joined, most often, by her mother, Demeter, the goddess of the harvest, and the two female deities who were most sacred to the ancient Sicilians share a divine presence that feels radical and innovative.

The Greeks may have been the most enthusiastic early overlords of Sicily — building some of their grandest temples here — but they appear not to have been the first conquerors. That honour belongs to the Phoenicians, whose contribution is summarised by the sudden appearance here of a madly grinning terracotta mask, made in Carthage and placed in a tomb to ward off evil spirits. It looks like a medieval gargoyle, and fulfilled more or less the same function — 2,000 years earlier.

Even the Greek art produced during their fruitful colonisation has an impishness about it, as if a native spirit has permeated it and subverted its decorum. The most startling evidence of this is another grimacing face, this time of a terracotta gorgon who sticks out her tongue and dares us to enter the building she protects so monstrously.

As the island had no marble and was short of stone for carving, terracotta was the preferred sculptural material. With characteristic inventiveness, the Sicilian Greeks began making their statues out of intricate combinations of stone and clay. A beautiful female head seen here, carved gently from white marble, would originally have had a limestone body, finished off, perhaps, with terracotta detailing. Even in their choice of materials, the ancient Sicilians created their wholes from many parts.

After the Greeks came the Romans. After the Romans came the Vandals. Then the Byzantines. Then the Arabs. Each of these dominant cultures brought something invigorating to the mix. You could hardly ask for a more hopeful artistic creation than the gorgeous ivory casket made in Sicily by skilled Islamic craftsmen, and decorated with a striking combination of abstracted plant forms and the standing figures of Christian saints.

The 150-year Arab rule in Sicily, which began in the 9th century, was an era of great intellectual achievement. No less than 170 Arab poets have been identified from the times. Among the most poignant objects in this display is the so-called Letter of Adelaide, a fragmentary Arab inscription instructing the Muslim officers of Enna to protect the Christian Abbey of San Filippo, which lay in their jurisdiction. The letter is written on paper, which the Arabs introduced into Sicily in the 10th century. It’s the oldest surviving paper document in Europe.

After defeating the Arabs in an extended conquest that began in 1061, the Normans turned out to be the most artistically productive of Sicily’s many landlords, successfully blending all the disparate influences that had previously arrived. Alas, the finest Norman achievements were architectural. The gorgeous Palatine Chapel, in Palermo, can only be hinted at in photographs. It is left here to a handful of fragments to evoke the marvellous artistic fusions created by the Normans. A beautiful marble inscription in flowing Arabic script used to decorate the doorway of the Palatine Chapel itself, where it instructed the reader to “contemplate the beauty that it contains”.

Most eloquent of all is an intricate wooden panel, taken from the roof of the Norman palace in Palermo, in which the swirling Fatimid geometry is interspersed with a Noah’s Ark of delicately carved animals: peacocks, wolves, hares, lions and eagles. In Norman Sicily, the lion and the deer had found a way to coexist.

Sicily: Culture and Conquest, British Museum, London WC1, until Aug 14