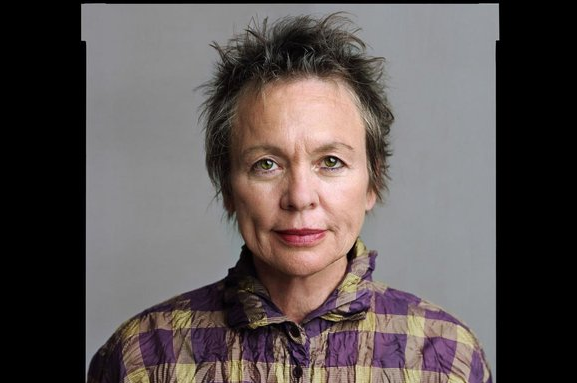

Laurie Anderson, the multitalented performance artist, musician and film-maker, doesn’t believe in heaven. Neither do I. But if I did believe in it, then I would have no difficulty imagining her as an angel. That’s how she strikes you, on stage and in the flesh — blonde, glowing, sweet, delicate, wise and ether eally innocent. Plus, she sings and plays the violin. And in art, beautiful blondes who play stringed instruments are most often found clustered around the celestial throne in representations of heaven. At least, that’s where they used to turn up in the Renaissance.

But, as I said, she doesn’t believe in an afterlife. Or in God. “I don’t think he’s up there, looking down,” she intones in that melodious voice of hers that makes every bit of prose sound like a song. “Even when I was five, I didn’t think you went anywhere after death. I thought the idea that you would be wearing crowns and hanging out somewhere else was absurd.”

We only re-met a few minutes ago at her studio in New York, and already she’s lecturing me on the meaning of life. Actually, “lecturing” isn’t what Anderson does. She doesn’t lecture. She infuses. She says things, and they seem to float into you like herbal tea infusing hot water. You would have thought there was a time and a place to talk about God. It’s not usually the subject of a promotional interview about the Brighton Festival, opening next month, of which she is the guest director. But with her, the big stuff is never off the agenda. And the little stuff feels strangely big as well.

If you don’t believe in God, what do you believe in? “I’m in this to be free. Everything is geared to that feeling — that you don’t have to follow any rules. I actually think we’re here to have a really, really, really good time. That’s what we’re here for. We’re not here for any other reason.”

A really, really, really good time? That sounds like the Brighton Festival all right. This year is its 50th, and judging by some of the archive footage that has been unearthed for the anniversary celebrations, Satan has played a larger role in these wild south-coast rip-ups than his better-reputed opposite. There’s nothing angelic about the way Keith Moon beat the hell out of his drum kit when the Who played the first festival in 1967. And poor Yehudi Menuhin looks more terrified than inspired as the screams of his violin supply the soundtrack for an impromptu beach-burning known as The Destruction of Hideous Objects.

Canal Street, in Lower Manhattan, where Anderson’s studio is located, has one thing in common with Brighton: it is by the water. Nothing else matches. Pockmarked, dirt-dark, set in a crummy riverside dead zone just before you get to the Holland Tunnel, this is the bit of Manhattan that the creatives abandoned. The only decorative thing left here is Anderson. On either side of her pint-sized building, huge commercial towers have stomped in and appear determined to eat her up.

Inside, her studio is decorated with plangent bits of furniture — a Philippe Starck chair, an array of tribal instruments — as well as lots of photos of her husband, Lou Reed, who died in 2013, and her dog, Lolabelle, who went in 2011. I knew them both. With Lou, I made a couple of films when I was at Channel 4, and, absurdly, he took me to Prague as his “translator” when he went to meet the president and longtime Velvet Underground fan Vaclav Havel. I explained to Lou that I spoke Polish, not Czech. It seemed not to matter. Polish was close enough.

Lolabelle I met when Lou and Laurie invited me to see the new apartment they were remodelling just up the river from Anderson’s studio. I took my little daughter with me, and to this day she remembers fondly playing all afternoon with Lolabelle while the adults yapped about Czechoslovakia.

In Britain, Anderson, 68, is best known — still — as the woman with glowing cheeks who sang O Superman back in 1981, and got to No 2. But away from these shores, she has since become an international performance superstar, jetting round the world, mounting ambitious projects wherever the invitations take her. The day after I meet her in Manhattan, she’s off to Panama. A couple of days earlier, she returned from Tennessee. So getting her to Brighton in May is an excellent feat of entrapment by the Brighton Festival.

For her romp by the sea, she has successfully placed Lolabelle and assorted doggy concerns at the centre of the action. One of the highlights will be the specially programmed Music for Dogs, featuring music from the tonal ranges Lolabelle preferred. The idea was initially prompted, she explains, by a conversation she had with Yo-Yo Ma during a speech day at the Rhode Island School of Design. Hot and bored, she turned to Yo-Yo and said: “You know, sometimes I look up and the whole audience is dogs.” And he said: “That’s my fantasy, too! Great. Whoever gets to do that first invites the other.” She got there first.

I got very twined up with Lou. I always will be. So it’s a weird death of yourself

Her main event at Brighton, however, will be a showing of Heart of a Dog, a film she’s made that was nominated for the Golden Lion at Venice and seems initially to be about Lolabelle, but gets sidetracked in typical Laurie Anderson fashion into all sorts of dense storylines about other things. In the end, it’s more about her than it is about the dog. And it’s about Lou. And it’s about life. And about death. And, of course, about love.

The beginning is weird. Drawn in a jittery but charming cartoon style, it shows her giving birth not to a human baby, but to Lolabelle, who arrives in the world swaddled and vulnerable, ready to be looked after by her new mum. “You just gave birth to a dog,” announces a proud cartoon doctor to the happy cartoon Laurie.

Her mother makes a nervy appearance as well. Not as the maternal presence you might expect, but as something of a Cruella de Vil: cold, haughty and unlovable. In the film’s most startling moment, her narrating daughter tells us calmly that she didn’t love her mother. Now, I’m Polish, and a mamma’s boy, so it took me aback. But, as usual, Laurie explains it with an instant smile: “Her mother didn’t love her, either. You know, you just punch the person down the line. That’s how it works. I know it’s not a popular thing, and people are, like, ‘Can you say that you don’t like your mother?’ I say, ‘You can say whatever you want. You can say how you feel.’”

She did, however, love her dad. As one of eight children growing up in Glen Ellyn, Illinois, she was one of those small-town girls about whom Lou Reed used to sing. Her dad was “always doing little dances. Telling jokes. Very warm. And I thought, ‘Men are great. They don’t have a care in the world. This is good. I like these guys.’”

She never wanted children. Neither did Lou. “Because I was number two of eight, I had a lot of child responsibilities. I couldn’t wait to leave. I couldn’t wait not to be responsible for a child. I wanted to be an artist. I just never had that instinct.”

Lou was the same. “He wanted to be a writer. He wanted to make beautiful things. So when we met, it was great. I don’t think we talked about that for a couple of years. It just wasn’t on my front burner. Ever.”

Clearly, though, it was on her back burner. Deep down, where it counts, Heart of a Dog is most often about who you bring into the world, and how you love them. Since the deaths of Lolabelle and Lou, she has had a new role to play, not just as the director of the Brighton Festival, but, more poignantly, as a grieving widow. And she’s taken to it with an astonishing positivity and lightness of touch.

“I got very twined up with Lou. I always will be. Actually, I kinda feel that he’s looking out of my eyes. It used to creep me out. But now I think, ‘Ah. Of course.’ You become so much a part of someone else, and they’re a part of you. So it’s a very weird type of death of yourself.

“It’s also an incredibly energising thing. It was completely a shock to me how much energy I felt. And how much gratitude for the time we had. I was not expecting that at all — this feeling of being dazzled by life.

“Being with him when he died was something I will never forget. His bravery. His happiness. His acceptance. It was a colossal experience for me. Changed my life completely in a way that I had not expected. I expected to feel sad and lost. But I felt the opposite. Just, like, ‘Boy, this is it. This is all we have. Right here. So you’d better pay attention.’”

And she laughs that gorgeous, angelic, tinkling laugh, and her eyes look up at me and glow with that angelic glow that is hers, and hers alone.

“The day before he died, we were out swimming in the pool. Looking at the trees. And he was just floating and saying, ‘You know, I am just so susceptible to beauty.’ And I think of that every day. Every day. How to open yourself to the world. And really appreciate it.”

Just as I’m leaving, she grabs me by the lift and tells me she will also be doing some stand-up at the festival.

Did you say stand-up? With jokes and all that?

“Aha,” she agrees. But before she can tell me more, the lift doors close and I plunge back down to earth. I had the feeling it was something she had just decided, there and then.

Laurie Anderson is guest director of the 50th edition of the Brighton Festival, May 7-29; brightonfestival.org. Heart of a Dog is on general release from May 20; the soundtrack is out now on Nonesuch