There is a sense in art at the moment of the past being relived. Several shows I have visited recently feel as if they are reaching back, beyond the 1990s, to the pre-Tate Modern era: to a time when contemporary art was less saleable, less smiley and, yes, less popular. Should we see it as a lament on the vapidity of today’s artistic culture? Yes, I think we should. It’s as if the current generation of curators has grown disillusioned with the mad success story that is contemporary art, and is seeking to remind us of a time when art meant something different. Something more.

I’m not talking here about nostalgia. That’s not what it is. Rather, it’s an effort to reposition things, to pull contemporary art out of the crazy commercial orbit in which it now revolves and return it to a pace at which things can stick. The Mona Hatoum show that has arrived at Tate Modern belongs to this trend. It’s a gently powerful event, largely monochrome in look, full of hints and shadows, and driven by political concerns that never announce themselves too shrilly. The politics are always there, but they drift in from the distance, like the faraway smell of someone cooking.

Hatoum was born in Beirut in 1952 to Palestinian parents. So the concerns of the Middle East were her bleak and inevitable birthright. When the Lebanese Civil War broke out, in 1975, she came to London to study art and began carving out for herself the deep and resonant career that Tate Modern remembers here so atmospherically.

Her first speciality in the capital was performance art. These days, performance art is uber-fashionable again — so fashionable that a large slab of Tate Modern’s £260m extension, due to open in June, is going to be devoted to it. In its earliest incarnations, however, performance wasn’t something you put on in £260m museum extensions. It was an art form that thrived in grubby alternative spaces or direct-action moments mounted in the street.

Hatoum’s best-known piece from the era, Roadworks, was enacted on the actual pavements of Brixton in the aftermath of the 1985 riots. Tying to her ankles a pair of clumpy black Dr Martens, of the kind sported by the riot police of the times, she trudged barefoot through the streets of Brixton, dragging the heavy police boots behind her. The contrast between her bare and vulnerable feet and the ponderous police bovver boots she towed seemed to comment poetically on the divide between victims and authorities. Tate Modern does a decent job of evoking the mood of Roadworks for us with plans, photos and descriptions, but what the piece really needs to complete the picture is the sound and the smell of Brixton burning.

The footage of Hatoum’s effortful clumping through south London reminded me also of the Friday procession in Old Jerusalem, at which Christ’s weary trudge to Golgotha is continuously re-enacted. Even in her most Londony London art, she is remembering, you feel, the darknesses and textures of her Levantine past.

Trying to give a sense of how these pioneering performances might have felt in the 1980s is a considerable exhibition challenge. This event’s curators meet it successfully, for the most part, with evocative clusters of information. They are helped by the anachronistic presence in the same galleries of a range of later works — sculptures and installations — in which Hatoum’s blossoming fascination with down-at-heel textures is fully in evidence.

Socle du Monde (Base of the World), from 1992-93, is a massive black cube, reminiscent immediately of the Kaaba, in Mecca, except that its surface is twisted into tight and hairy knots, as if the Kaaba had been remade in astrakhan. A closer inspection reveals it isn’t astrakhan — the foetal fur of unborn lambs — at all, but a dense cosmos of iron filings held in place by magnets.

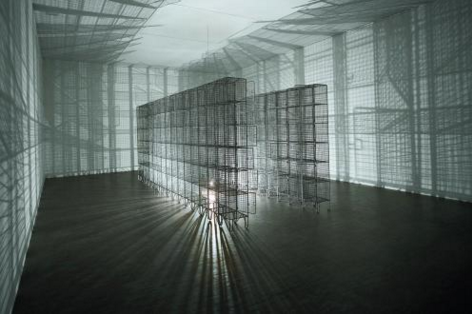

As with the art of Joseph Beuys, the evocative materials she works with do much of the talking for her. Light Sentence, also from 1992, is a creepy room installation in which an arrangement of harsh wire cages, lit by a single lightbulb, projects sinister Hitchcockian shadows onto the walls. On and on they go, reflected and repeated, until the sense of incarceration with which they fill the space takes on a cosmic ubiquity.

All this is out of sequence. But the show is chronological enough in the main to allow us to discern an arc in her progress. Until 1995, Hatoum was conspicuously a political artist. Even a video work as evidently and unwatchably biological as Corps étranger, from 1994 — created by exploring her own mucky orifices with an endoscopic camera — had ambitions to comment on the surveillance society that Britain was becoming.

From now on, though, the politics of her art become harder to spot as the sharp elbows of her early performances are replaced by tender hugs and emotional laments on the human condition. Van Gogh, of all people, emerges as an influence in works such as the sad domestic installation in which Hatoum remembers the simplicity and sparseness of her bedroom in Beirut. A bed, a chair and a desk were all she had in there. Earlier in the show, a view of a man’s hairy back soaped into cosmic swirls, like the sky in The Starry Night, is actually called Van Gogh’s Back.

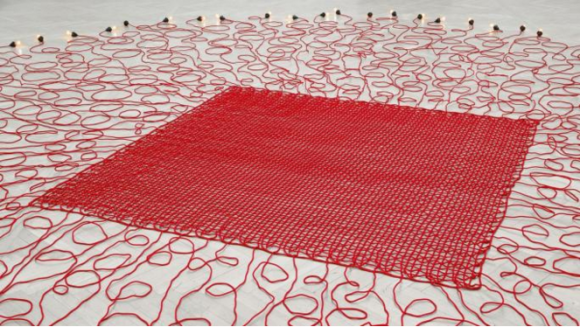

But the most striking evidence of her sensitivity to textures is the work she produces with female hair. There’s a lot of it in the show — and all of it is charged with a transgressive power, as if it is being used to cast a spell. Keffieh, from 1993-99, is a traditional Arabic headdress, as worn by men, but made in this instance out of a fine weave of female hair. A masculine society, you feel, is being challenged from within by edgy feminine insights.

By this point in the show, Hatoum has turned into a poetic minimalist: a creator of ambiguous sights and sculptures in which the meanings are conveyed by poetic juxtapositions. And since poetic juxtapositions are an imprecise way of conveying meanings, we are confronted by a body of work that whispers mysterious things to your senses.

These days, Hatoum is something of an international art star, dashing between the continents from this biennale to that. As a female artist with a long and serious past, she is the kind of figure that modern curators adore. Nowhere at this event, however, can you confidently assume that the harsh history into which she was born is behind her. Her recent work never descends into agitprop. It never preaches. But neither does it forget.

Impenetrable, from 2009, appears at first sight to be a delicate filigree of suspended lines that form a lovely see-through cube in the room. Only when you get closer do you realise that the lines are made out of barbed wire, and that the delicate filigree would tear chunks out of you if you stepped into it.

Mona Hatoum, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Aug 21