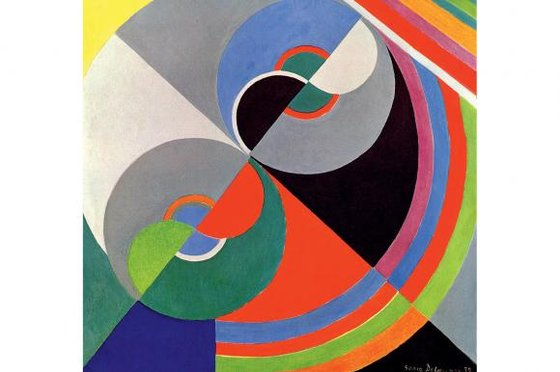

Sonia Delaunay has never brought me any luck. A set of her trademark circles of swirling colour decorates the back of my preferred pack of playing cards, the ones I’ve used for losing at bridge, then gin rummy, then poker, then three-card brag, and now, most uselessly, at snap. My decline as a card player is written into every crease and tear of that pack. I have vivid memories of staring with immense concentration, for losing hand after losing hand, at Sonia Delaunay’s lovely catherine wheels of loss.

This goes back a long way. The pack was bought in Paris in my student days, when Delaunay was viewed by all and sundry as a failed artist. The storyline attached to her then — glued to her — was of a pioneering abstract painter who briefly achieved good things in the early days of modernism, but then slipped feebly into an inconsequential career as a designer. Delaunay’s jaunty dresses and headscarves were perfect for summers in the south of France — no argument there — but they no longer qualified for serious consideration in the annals of modern art.

That is the storyline that prevailed for the entire second half of the 20th century and which the ambitious reconsideration of her career that has now turned up at Tate Modern is determined to rewrite. Good luck to them.

She was born Sara Elievna Stern in Odessa in 1885. Her family was Jewish. When she was seven, she was sent away to St Petersburg, where she lived with her uncle’s family and turned, as if by magic, into Sonia Terk, opinionated St Petersburg intellectual who wanted to be a painter. This first transformation isn’t explained in the show or its catalogue. Neither is the next one. When we encounter her here, Sara Elievna Stern from Odessa has already become Sonia Delaunay, modernist from Montparnasse.

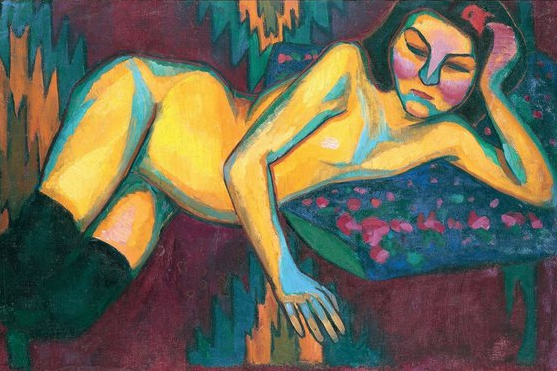

The opening room is filled with fiercely derivative but by no means unappealing portraits in the manner of Matisse and the fauves. Dark female heads with purple noses are set against black wallpaper with red spots. An angular yellow nude with sharp German expressionist elbows sprawls bonily on a decorated cushion. All this is obviously copied from the art around her, but the speed of the absorption is impressive.

Some of the credit for the superfast catch-up must presumably lie with the progressive art dealer Wilhelm Uhde, who pops up in one of Picasso’s best cubist portraits and whom she married in 1908. Uhde was a homosexual. So the marriage was a sham. But it worked. Sonia Terk didn’t have to go back to her uncle’s house in St Petersburg and could settle down in her new one in Paris.

Within a few months, she had pink-period Picasso down to a T as well. And in the show’s best early moment, she paints a set of taut and angular portraits of an adolescent Finnish girl with cheekbones worthy of a Kazakh goatherd. Gauguin inspired the exotic new colour scheme of pinks, yellows and blues. But the atmosphere of the totemic female face, with the spare outline of a Buddhist wood carving, is a direct borrowing from Picasso, c 1906.

I list all this in admiration. To get up to speed this quickly is commendable as well as revealing. We are dealing with a quick mind that can borrow instantly from this look and that. Delaunay’s next transformation is even more abrupt. One moment she’s painting people, the next they’re gone for ever, replaced until the show’s end by the trademark circles of concentric colour that I’ve stared at so often in so many winning hands arranged against me across the table.

The explanation on the walls tells us that it was her meeting with Robert Delaunay, a like-minded painter of light, that triggered this big jump into abstraction. Leaving Uhde in 1909, she moved in with Delaunay, and the two of them came up swiftly with two developments: a baby son called Charles, and a new ism they christened simultanism.

It’s here, in the earliest days of the switch to abstraction, that the show is at its most stimulating. What should suddenly loom up before us in a vitrine but a patchwork dress full of vibrating triangles of colour that she sewed herself and apparently wore to the tango halls that were now all the rage in Paris. Robert, meanwhile, sported the snazzy simultanist waistcoat she also made for him. As for their baby, he got a tiny and lovely cradle cover, cut from a dense geometry of black, purple and yellow triangles.

The paintings that accompany this sudden plunge into domestic abstraction are some of the exhibition’s finest. Electric Prisms, from 1914, which you’ll recognise from your visits to the Centre Pompidou, is a huge Eton mess of colour, swirling in exciting vortexes — imagine 100 Rothkos thrown into a tumble dryer. Le Bal Bullier is a tango scene in which light-filled clusters of half-glimpsed figures progress ecstatically across the canvas at the speed of an unrolling carpet.

So far, so good. In a few manic years of progress, Sonia Delaunay has successfully gone from copycat fauve to geometric abstractionist. It’s what happens next that will divide opinion.

Most of the display that follows consists of dresses, textiles, handbags, swimwear and book covers. Having recognised the possibilities of pure design, having reawakened in herself an interest in Russian folk-art methods and forms, Delaunay sets about becoming an instantly recognisable design brand. At no point does she stop painting entirely. Indeed, in the final rooms she returns once more to her brightly abstract canvases. But what does cease is any development of mood, depth, tone or range. Having arrived so quickly at the trademark concentric circles of simultanism, she spends the next 70 years of her career — she died in 1979, aged 94 — producing small variations on the same basic design.

How should we view this? From the organisers’ standpoint, she should now be recognised as a female pioneer whose appropriation of specifically feminine methods and materials was every bit as revolutionary in its effect as any of the big stylistic lurches engineered by the blokes of modernism. Sonia Delaunay, the show argues, is a highly original artist in need of a “radical reassessment”. Many of today’s artists are now working her way.

Unfortunately, I don’t buy the argument that switching from paintings to dresses is a radical creative step. The problem with Delaunay is not that she expressed herself in dresses and fabrics, or that she embarked upon a set of wide- ranging creative endeavours that had not previously been taken seriously as art. The problem is that the visual language she arrived at and kept repeating transports us nowhere and says nothing of any resonance.

Sorry, but take any five years of Picasso’s oeuvre, and you will see more range in mood, subject matter, technique and depth than this event manages in a dozen ambitious galleries. Sure, what Delaunay made was often lovely. But when did that become enough?

Sonia Delaunay, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Aug 9