Cricket lovers, have you bought your new Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack? You must. Not because it has Moeen Ali on the cover, smiling broadly, beard a-bristling. Ali’s a good thing, of course, and I, too, had my hopes raised by that 128 he scored against Scotland in the World Cup. But nice as it is to have him on the 2015 Wisden, it is not, perhaps, reason enough to buy it.

For that you need to look higher, to the top of the cover, where, as always, you will find that charming woodcut by Eric Ravilious of two Victorian gentlemen playing cricket. The one on the right is clouting a six. The one on the left is keeping wicket. I am not saying, get the book, cut out the Ravilious cricketers, frame them and throw away the rest. That would be rude. But yes, I admit, the temptation is there.

Ravilious’s woodcut has been appearing annually on the cover of Wisden since 1938. When he produced it, it was just a tiny droplet in the torrent of book and poster illustrations pouring out of him at the time. But it had about it that quiet stubbornness you often get with his imagery. His work can feel bland, until you try to dislodge it from your memory. And find that you can’t.

Ravilious (1903-42) was, apparently, a keen village cricketer himself. Anyone visiting the delightful and haunting retrospective of his career that has opened at the Dulwich Picture Gallery will have no difficulty recognising the gentle paralleling of colour schemes and tempos that takes place here between the Lord’s player and the English watercolourist.

That classic cricketing combination of white on green is also the one that dominates Ravilious’s views of the cliffs at Beachy Head or his looming image of the chalk horse at Westbury. That lovely expanse of outdoor flatness that trundles past you at Derek Pringle pace through the window of the railway carriage in his famous Train Landscape of 1940 is definitely a perfect batting surface on which the bounce is true. Art doesn’t get much more English or archetypal than this. And yet…

Ravilious was just 39 when he died in a wartime plane crash in 1942, so he only reached number four in Shakespeare’s seven ages of man. Within this short innings, his art seemed hardly to change in tone or scope. So to give his journey some shape, the Dulwich show has arranged his output in helpful thematic clusters. Nothing too rigid. Indoor scenes here. Places and seasons there. A section that deals with the dark. Another that deals with the light.

Two things struck me from the opening clutch of images. The first was the absence of people in them. He could do people, as the Wisden cricketers annually prove, but seemed keener not to. Alone, you feel, it was easier to reach that state of ecstatic quivering at the sights before him that Ravilious conveys so inventively in his best pictures. Even when all he does is come across a broken car in a junkyard, or an old bus pushed up on some beer barrels, you sense the thrill of discovery. He’s in his mid-thirties by now, yet these are still the heightened emotions schoolboys feel when they’re out scrumping. Later, when he paints the beautiful dawns rising above the Sussex Downs, or, later still, the explosions bursting from the sides of British destroyers in action at night in the Norway fjords, the sense of ecstatic transportation is still there. This is a drug addict whose drug was looking.

The second thing that struck me was his sharp taste for surrealism. Ravilious was one of those artists who could spot something strange in any normality. That big yellow thing on a railway wagon that pops up in a snow scene is a propeller from a ship. But a spaceship from Mars would not have looked more out of context.

Even the fact that these awkward sights are all recorded in watercolour seems to stoke the unease. Usually a foggy medium, noted for its evocative generosity, watercolour, in Ravilious’s obsessive hands, becomes a means of capturing utterly specific atmospheric effects. Using techniques borrowed inventively from printmaking — hatching, patching, dotting, quilting — he builds up his skies and horizons as precisely as an engineer drawing a graph.

A sense of ecstatic transportation: Midnight Sun, 1940These are useful and pioneering observations. For most of the 20th century, Ravilious was viewed as an anachronism: an out-of-time English watercolourist, with out-of-time English tastes, who had somehow survived into the century of Picasso, Malevich and Pollock. The Dulwich show sets this record straight by making obvious how much prickly invention was actually involved in producing these haunting watercolours.

Having introduced us to his outdoor surrealism, the show takes us indoors next to his even spookier interiors. The least welcoming of these feature some empty beds in some empty rooms. And that’s it. The catalogue cites Van Gogh’s paintings of his bedroom in Arles as an influence, which is surely right, but where Van Gogh’s bedroom is a site of whirling human passions, Ravilious’s Psycho spaces are empty of everything except their intense poetic strangeness: the bedroom as sinister ready-made.

Tellingly, in Eastbourne, where he was brought up, his parents ran an antique shop. It’s probably a bit pat to conclude that his interest in curious objects with an air of displacement about them was triggered by the sights in that shop. Or that his appetite for big skies and ecstatic horizons was inherited directly from the huge beach views you get in out-of-season Sussex. But something of that order surely took place?

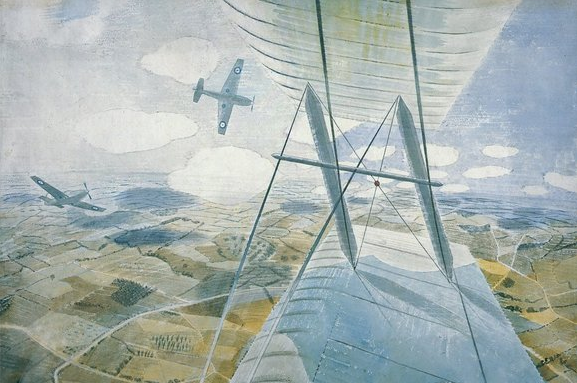

I was particularly impressed by the various war pictures gathered here. Made an official war artist in 1939, Ravilious appeared to respond to the man-made spectacle of war with the same delight he displayed in front of nature.

The show’s masterpiece is, of all things, a view of HMS Ark Royal retreating from the enemy at Narvik in 1940. The sky is filled with glowing debris, the sea bubbles as if it were boiling, the Ark Royal itself is surrounded by fireballs, yet the artist seems to savour the cosmic excitement of it all as if he were watching a really good bonfire night.

Ravilious, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London SE21, until Aug 31