British art has plenty of knockers. Oops. Let me rephrase that, in case all you Carry On Culture readers out there have begun imagining galleries full of nude Barbara Windsors. British art has many detractors. Writing in 1854, the German poet Heinrich Heine, whose work had been set famously to music by Schubert, opined that “there is nothing on earth more terrible than English music, except English painting”. It’s a view that has persisted.

I remember Picasso dismissing Henry Moore as a “petit maître”. And long before Picasso or Heine, there was Hogarth, curling his lip and writing to Horace Walpole: “I think it owing to the good sense of the English that they have not painted better.” Ouch.

In our own times, this disregard of the national art has become institutionalised. On my watch as an art critic, I have witnessed British art sinking before my eyes as an object of affection and attention. Galleries such as the Serpentine in Kensington Gardens, which used to play such an active role in the development of contemporary art in Britain, have been turned, instead, into posh caravanserai on the curatorial Silk Road that stretches, these days, from Istanbul to Sao Paulo. Looking for a Serpentine curator? Try Beijing not Bethnal Green.

Tate Britain, meanwhile, an institution charged specifically with the care and understanding of the national art, has been a disaster. Show after show in recent years has chosen to play worthless games of cultural snap across the ages when it ought to have been digging deeper into the story of British art. In its desperation to become a kind of Tate Modern lite, the Millbank franchise has seen an unforgivable drop in the quality of its scholarship. Not only has the gallery’s identity been lost, so, too, has its audience. As my colleague Hugh Pearman tweeted the other day, even on a Sunday afternoon in the Easter holidays, the place is deserted.

Compare that with the Dulwich Picture Gallery, where a delightful investigation of the underappreciated art of Eric Ravilious has been pulling in the crowds and proving that British art is not something about which we should be embarrassed. Scholarly, involving, paradigm-shifting, the Ravilious exhibition is exactly the kind of event that Tate Britain should be putting on, but isn’t.

I write all this not as a jingoist or as some kind of anti-internationalist. Look at my name. I write this as someone who believes that British art has been ignored by those who should not be ignoring it. All of which is a very, very long-winded way of getting to Cornelius Johnson and the pleasing little display devoted to him that has arrived at the National Portrait Gallery.

This, too, is a show Tate Britain should have mounted. Looking at the labels, I was disappointed to see that half the pictures actually come from the Tate collection. It’s just that they’re never on show there.

Johnson (1593-1661) was Britain’s leading portrait painter in the early years of Charles I. His misfortune was to be a near-contemporary of Van Dyck, whose enormous impact on British art left many a smaller talent buried in the rubble. As the NPG announces in its title, Cornelius Johnson was “Charles I’s Forgotten Painter”.

And Charles I’s reign wasn’t any old royal reign. The Civil War in which it ended was an event of gigantic national import. To have been present, as Johnson was, in the build-up to Charles’s beheading and Cromwell’s Puritan revolution marks him out as an especially valuable witness. Amazingly, the helpful little book by Karen Hearn that accompanies this event is the first ever on Cornelius Johnson. I’ve never seen a show about him before.

The NPG’s effort is too small to right this wrong on its own. Set in a single room, it’s anamuse-bouche of an event, fewer than a dozen pictures, tiny and tempting. To make things even less solid, Johnson’s background was highly confusing.

Born in London in 1593, he seems to have been of German origin, one of the many displaced Protestant talents circling through western Europe in these messy years of religious strife. Until he fled to the Netherlands in 1643, to escape the Civil War, he was understood by all and sundry as a British artist. But after 1643, that changed. His Wikipedia entry actually has him down as Cornelis Janssens van Ceulen, even though that was a name he never used.

These confusions about who and what he was have perhaps contributed to his neglect. British art historians had him down as a Dutchman. Dutch art historians had him down as an Englishman. But in her book, Hearn sticks with Cornelius Johnson, and pins him firmly to the dartboard with the news that he was the first British artist consistently to sign and date his pictures. We may have trouble with his identity, but Johnson himself obviously did not.

One such signature — “CJ fecit 1620” — sits proudly in the corner of his marvellous portrait of Susanna Temple, later to become Lady Lister. She poses in a pretend oval of marble, as if she were looking through the porthole of a ship made of stone. Her dress and lace ruff have been minutely painted, with no shortcuts, bringing a sense of off-the-peg stiffness in her pose. But her face has something about it. A twinkle. A humanity. When you lean closer, you see that the paintwork around her mouth, eyes and hair has begun to take descriptive risks. A good decade older than Rembrandt, and nothing like as brilliant, Johnson paints people whose thoughts you can feel. It is this tangible psychological presence, more than the signatures and the dates, that marks him out as a British artist of note.

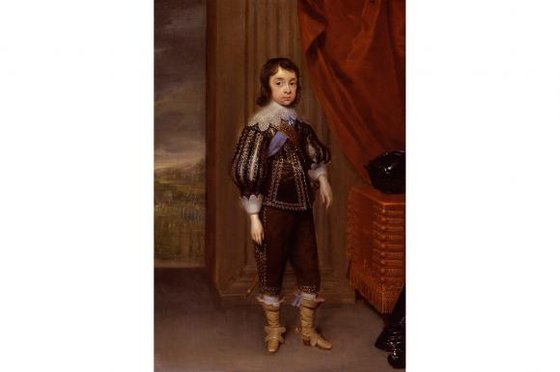

Alas, he was also mightily prolific, and even in this petite selection the weak Johnsons outnumber the strong. Appointed in 1632 as “his Majesty’s servant in ye quality of picture Drawer to his Majesty”, he makes an unconvincing stab at royal portraiture in three full-lengths of the Stuart monarchs-in-waiting. Tiny and disproportionate, with faces that seem too large for their bodies, Charles, James and Mary form a trio of Tom Thumbs — reduced adults rather than proper children. The most ambitious painting here, a near-life-size group portrait of the Capel family, makes a decent stab at the adults, but falls apart with the kids. Single figures from the chest up — that’s what Johnson did best.

In the Netherlands, after 1643, it took him a while to rebuild his reputation — with the excellent result that his first Dutch portraits make a special effort. It’s particularly noticeable in the fine portrait of Apolonius Veth, from 1644, in which the simple lace collar is painted as impressively as the thoughtful face above it. Not even Van Dyck, genius though he was, ever struck a note of human seriousness as resonant across the ages as the one struck by Cornelius Johnson in his stern portrait of Apolonius Veth.

Cornelius Johnson: Charles I’s Forgotten Painter, at the National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, until Sept 13